Were you exasperated and disgusted by her, as an extreme form of yourself? Your wild talk, your turbulent moods, your ‘dark places’? Mental illness frightens you, like a contagion.

Joyce Carol Oates

To watch me love another is to gain insight into the many complex ways in which I may still hate myself. I am reckless. I am desperate. I am provocative. I am extreme.

I know a capacity to give myself away that transcends age, gender, circumstance. When I do so, I crucify myself on each detail: in rushes of intolerable empathy laced with egoism, I impale myself on the subtleties of another’s existence. I feel everything. I have to. Why else would I climb each cross so willingly?

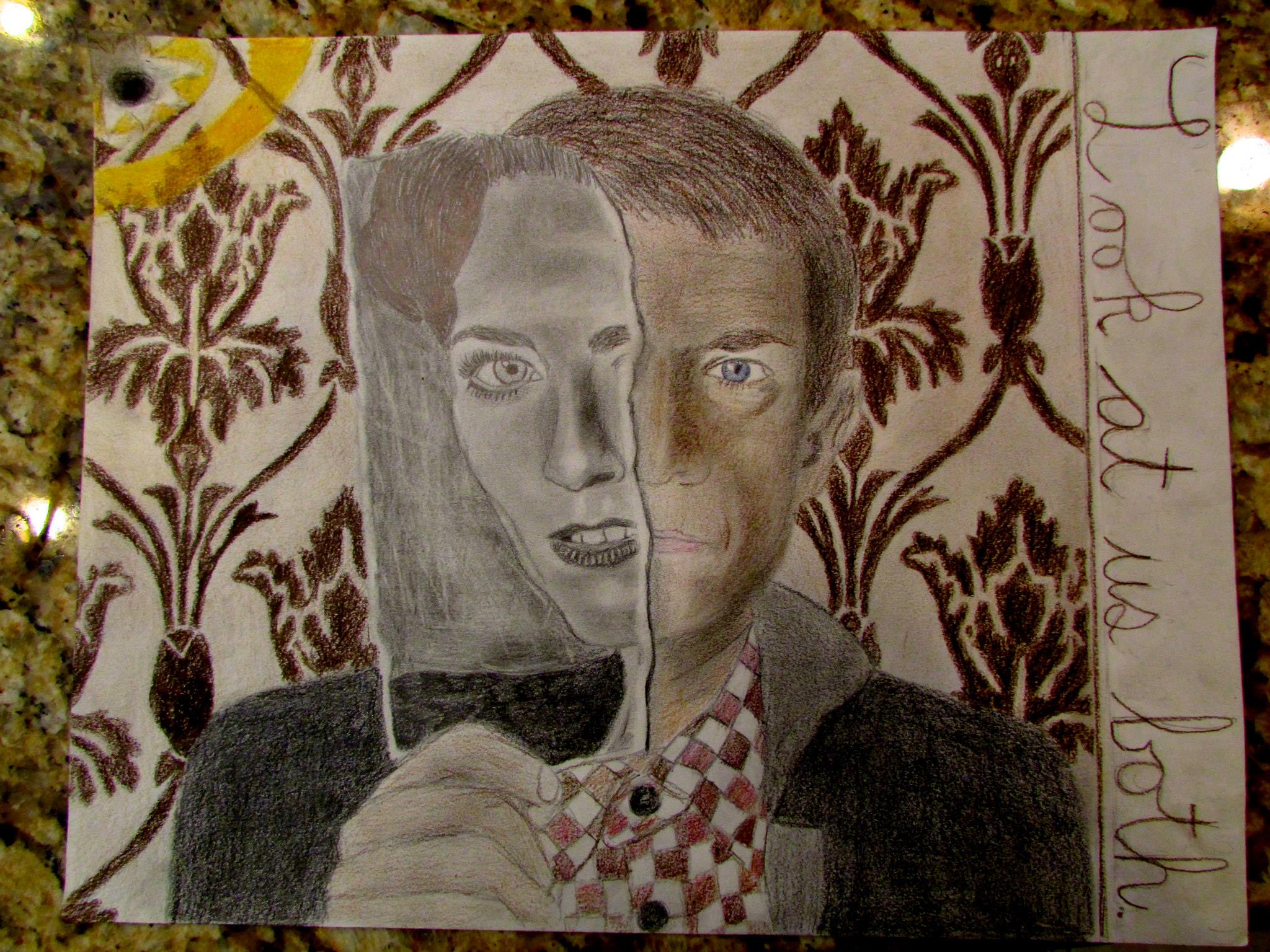

Maybe underneath it all, in the secret core of our cowering souls, we all crave subjugation. I dread every new morning, every self-reproaching glance in the mirror, my own chastising gaze. I navigate convoluted prisms of desire, performativity, and shame. What new horror have I inflicted upon myself? What will I have to live with today?

To reduce my writings to “commentary” on any one person, place, or event, is to misconstrue entirely the nature and the purpose of my work. To speak more clearly: I do not write this in response to any particular element of my present life. I am as happy now as I ever have been, or perhaps ever can be. The plane upon which my writing operates differs greatly from whatever reality textures my daily existence. This is not simply a piece about “my life.”

No, this is the litany of a violent soul in stasis and a mind only slightly unhinged: with no circumstantial catastrophe to engage it, such energy inevitably devours itself. Unexpectedly, but not inexplicably, I am reckoning with the turbulent forces of a mind and a conscience that I always thought I understood. My work is antithetical to my sanity; my art enters into a conflict with myself.

I am thinking on symbols and sensuality: I must live within a language that is no longer my own. An ancient sacred agency was taken from me, while rhythms and rituals recall what I am. And what I am is a neurotic, in the most organic sense. I wish to be open. I want pleasure, tenderness, and melancholic dissonance to infuse my volatile soul. I am not adjusted to the world—I am adjusted to myself. I crave ecstasy, and when this life offers less than I can endure, I engage in relentless acts of self-consumption. I am both satisfied and insatiable, drenched in a certain desirous impulse, the specter of which haunts this visceral consciousness.

How, after all, can I experience an entire world, so vast and mercurial, through a single body? The inimitable allure of literature and of music in the streets: the sheer stimulation of these people, this place. I can play a guitar until my fingers bleed, but sensation still boils beneath the surface of my skin. Self-mutilation is only a memory now, never to be revisited—but in moments of almost unendurable ecstasy, I sometimes imagine that if I were to open my own skin once more, my inner self would be revealed not in anemic drops, but in radiant prisms of light.

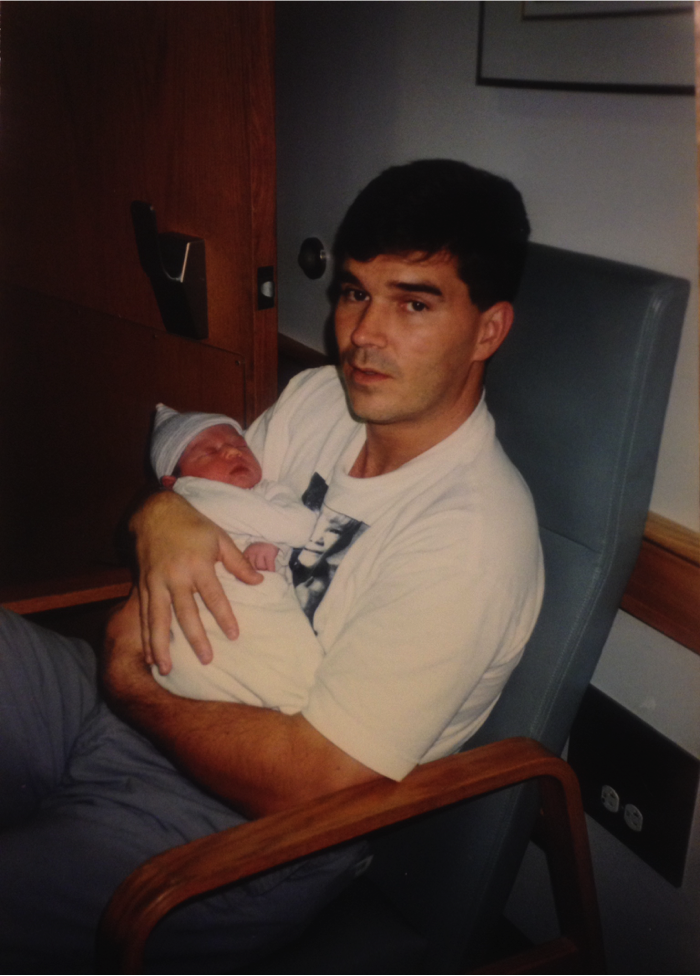

I will never love anyone the way I loved my father. No one will ever love me the way my mother has. Some people are intrigued by what I present to them: they want to interrogate it, engage with it. But who would ever stay? What person could reckon, willingly, with the violence of what I am? At the extreme risk of self-debasement I engage wholly with my own passionate impulses. If I do not take myself seriously, who else will or can?

And so I am, in some ways, a narcissist. It is not the person that matters to me, but the figure: its relevance, its positionality and calibration within my life. My egoism is empathetic: my love is rapid and deep, but directionless. I cannot yet (or can no longer) emulate that mature, private, constant adoration that constitutes a “stable ideal.” I cannot always feel this way. I will forget this sensation, but will remember experiencing it. And then I will forget that too. My present self will be explicable, but not justifiable, to whatever I become.

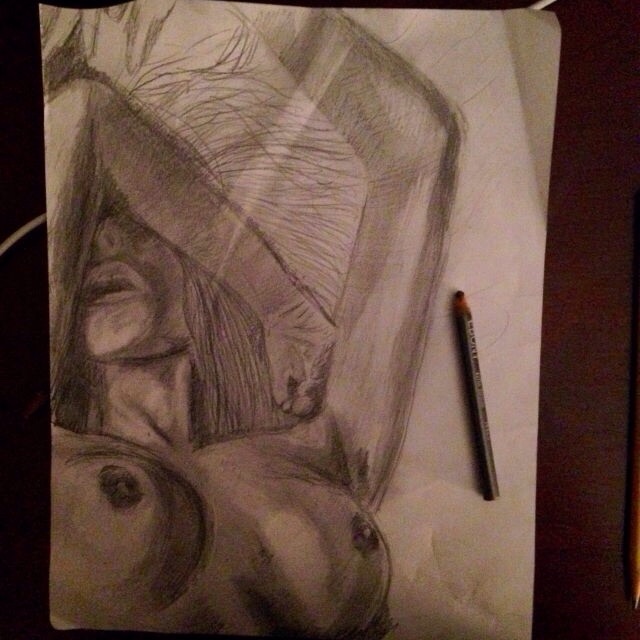

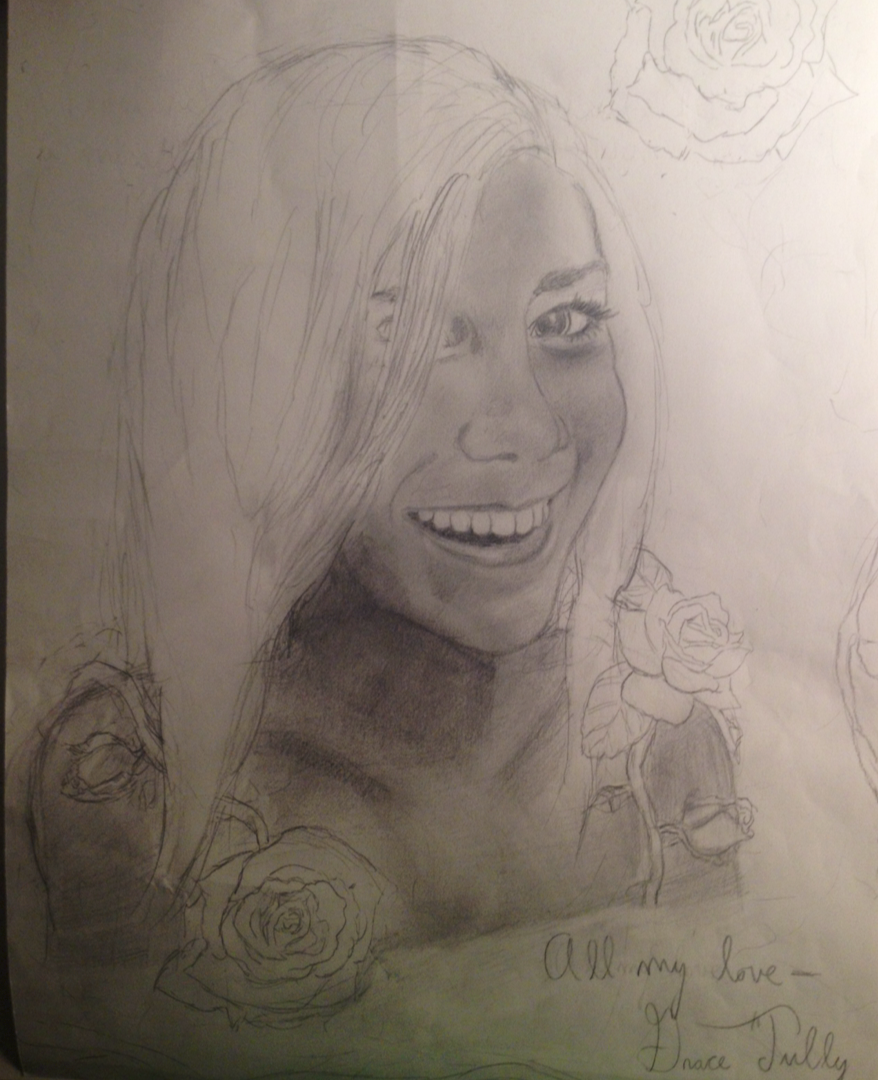

In the ardent haze of summer, I knew an artist, and in an erotic act of desire, decision, and resilience, she painted me. This was a piece about womanhood, about ecstasy, about me. Across the top she wrote “Always,” and being who I am, I believed it. Sometimes I still do.

But just months later, I wandered autumnal streets slick with rainwater and lamplight, with a young man who was both disarmingly vulnerable and fascinatingly inaccessible. He had a mind that was captivating and disarrayed, and expressive, deep-set eyes the color of morning. In his sanguine, gentle consciousness, I misremembered myself. I knew a different kind of tenderness than that which had preceded him.

One morning, I awoke to glass windowpanes slick with frost. On the floor beside the bed, pale light had fallen across our garments. They were strewn across the painting, which lay on the floor where I had left it unfurled. I stared at the soft, stained fabrics that belonged to me: fragile lace, crimson in color, precisely the same shade as those tenderly bleeding words. Always.

Beside me, another body, the geography of which I had explored beneath my fingertips like every one before it, was sleeping soundly, breathing softly, knowing little, caring less. A sensual dispersion of paint across canvas, that passionate memory of lesbian desire: it seemed so strangely at odds with the cast-off clothing of the woman it had memorialized, and the young man now asleep in her bed.

It was pretentious, it was absurd, but for the briefest moment I felt older. Like I had lived and loved a lifetime’s worth. I felt tired and I felt alive.

Then I realized that I had forgotten the precise color of her eyes. Well fuck, what then?

Yes, it fades, it always fades: all I ever need is another figure, another body, another site of imposition for the discursive passion that colours my mind. Sometimes these desires replicate in my own physicality: another cigarette, another skipped meal, another sleepless night. I pace the silence at the edge of my bed until I hear my name drop softly from another’s lips. It is as beautiful as it is damning. I remember everyone that I meet.

Ancient cities of intellect and romance constitute a peculiar sense of home for the woman who wanders their capillaries. Spires dream and I am wide-awake with the morning. Cobblestone streets work their way into the contours of my soul.

I am growing, changing, becoming. I feel too deeply. No body can contain me. I cannot be alone—not ever. Except that I already am. I always have been. I consume (and in doing so nourish) myself.

The sun had not yet fully risen in the sky when I locked the bathroom door behind me and stared hard at my reflection in the mirror. His breathing fell like rain against windowpanes, echoing through my mind on that cold grey morning; and as I slowly took in the guarded eyes, half-shaved hair, and scarred skin of the girl standing before me, there was nothing left to do but wonder what the hell had happened to her, and when.

Recent Comments