Page 8 of 10

It is the difference between planetary light and the combustion of stars.

E.B. White, The Ring of Time

Frigid currents of ink move in and around me: I lie still. Back arched, skin shivering pale, my eyes trace breathless patterns across a ceiling of mirrors. Some nights are easier than others. In shades of masochism, I disallow pleasure: I am not in pain, not exactly, but nearing it. My mind, like my body, resists its own desires—it is the final refuge of a form that has been wounded over and over again.

I wish that I had been found some years ago, before my soul was all scar tissue and rust: the debris of celestial bodies long past their time. How low and sorrowful, that one should only ever know the fading fires of their glory and their lust. How fragile and peculiar, that anyone could care for a thing so lost.

But then I feel my own self move: the skin and warmth, the vulnerability and vanity. Trauma bleeds out and away from whatever I am, as silver idioms fall from my mouth like fragments of the moon. In the amber haze of my own endurance, gentle hands revive the parts of me that have not yet been mutilated beyond repair: the mournful bones that murmur with sensation, the folds of skin still dusted with fading starlight. I awake bearing bruises that span this form like constellations, whispering nebulous patterns across my skin. The pleasure is so simple, so profound: to allow someone to love this tainted frame, to feel affection on its surface even when I cannot respond in full, is beautiful in its own right. Withdrawn and wretched though I may have become, my flesh remains a sanctuary upon which tenderness is still possible.

Enticed by the presence of each new fascination, I have lived these weeks within the subtle variations of music changing key. This is not a cosmic shift in circumstance, not the onset of a lasting passion, not the tremendous recalibration that accompanies a catastrophe or a muse. It is, in fact, almost poignant in its subtlety. I am affected, intrigued, even burning softly—but this will not destroy me. And how futile, how tedious that can feel.

But is it possible, perhaps, that I am healing? That maybe this is a different way of feeling and creating, dissociated entirely from the madness of the one who nearly drove me from my mind? The pain of that ending was damning, even for me: we were wasting my final cigarette on a poorly lit street corner when, without warning or provocation, my memory engaged at last with the full ramifications of my spent time. I watched the dispersion of ash across his fingernails, and desired suddenly to shake him, to scream, Meet my eyes. Say my name. There’s nothing! You’re empty, you’re empty—

And how was he to have appeased me, being so directionless, so undone? The answer emerges in its own futility: I never wanted to be appeased. I wanted to thrill him, to hurt him, to make him feel anything at all. When we made love, I wanted to tear him apart and work my way inside of him, to wrest something of value from that wasted mind. I wanted to undo each vertebral ridge, lace my fingers through the notches in his spine; I wanted to pull the lovely skin away and expose a labyrinth of bone. I wanted to dissemble him, that poor desperate thing, and breathe some sort of life into whatever remained. I wanted to punish and save him: I wanted to play God. Perhaps I would rather know my own value than ever love like that again.

But then, maybe that is not the whole truth of it. Maybe it was simpler and less cruel. Maybe I really did recognize something of myself in that gentle, disarrayed countenance. Maybe I just wanted to love something—to love anything at all.

When he passes I still feel him, still smell him; my entire body still reacts. He floods me like an opportunity wasted, but this time I am not at fault. I cannot love something half-alive; even at my strongest, I never could have. My mind reacts against that peril, recoils from the decisions that my mother made before me. I have to be better, and stronger, and closer to blameless—and if such severance mandates apathy, then may I never feel again.

But in the margins of my lucidity, his image haunts me still. Not even a week ago, I was reminded of this, as I lay in the arms of the woman who had shared my bed through the night. It was my waking mind that dreamt of him, and that was the most frightening of all. But it was dreaming all the same, and no less for my sentient state; I was conscious but not present, if you understand. And he was walking down empty streets drenched in rain and silence, his hands in his pockets, younger and stronger and unmarred by circumstance. I knew at once that he must have died to have been rendered so perfect, so complete. There was nothing left to be done, so we simply spoke on: and there were no secrets to draw back from, no deficiency in either of our minds. I felt no pain and his eyes seemed like the morning to me once more.

But fortitude is an exercise in self-denial. So I left the sleeping girl where she lay, her dark hair strewn about her shoulders, her raised scars gleaming faintly in the half-light. Kneeling beside the cluttered bedroom table, I cast myself again into that cold, clean high to which I have become so partial: the lucid currents that flood my veins like shards of glass and crystal, setting my teeth on edge, making me wish to set my past on fire and walk away without a word. But a history such as mine does not burn easily; it burns like flesh, and festers. With each new, self-inflicted horror, I remember that it never really fades.

Eight months ago, in late summer, the dawn sky was flooded with a gradient of muted tones. I was sharing cheap vodka, stale cigarettes, and half-remembered confessions with a young man I had met only hours previously. In the haze of that soon-to-be morning, I knew him as well as I have ever known another living being. I cannot recall what fear or desire I must have expressed, in the midst of those shared ruminations, but a response fell from his mouth with such simple conviction that I will remember each word for the rest of my life—

“You can’t seem to be anything other than what you are—you’re so you—and it’s funny, and it’s admirable, and it’s sad, and people are going to put you on a stage because they won’t know what else to do with you. And you’re going to have to be strong because of that.”

In the half-year that followed, I hardly knew what to make of so strange an assertion. After all, my own desires had always been so simple: to write, to speak, to not hurt. But when people mistake survival for performance, they judge it as such—that is only to be expected. And childhood was wasted on me, even before it went so wrong: I was always melancholic, always peculiar. People noticed, though I wish to God they never had. They made me feel different. I never wanted to feel different.

I want to be clear—I am not trying to martyr myself. My methods of endurance are flawed, to say the very least, and I am far from inculpable. But I am not performing. I never have been. I tried to be better, exhausted my sanity on efforts towards the normalcy that I was sure would bring acceptance. And for my part, I found it degrading. How could I even begin to forget what I am? Who would ever let me?

I have loved recklessly. I have bled with deliberation. I have felt my entire form buckle below the weight of the memories I cannot keep at bay. I have lied and grown listless: I have tried to die time and time again. Shall I go on—recall the hands on the back of my neck, the profane helplessness of my shame? Whatever this mind has done to me, whatever it is doing, it provided solace when nothing else would. Were I anything other than what I am, then I would be nothing at all. So I will not suffer to be made a spectacle of, will not look on as my survival is cheapened to a dirty joke. I imagine that even the most cynical among you can forgive me for that.

In the early months of winter, I wished to know what it felt like to heal. I sought a long-awaited beginning, and of course I did not find that: I never really expected to. But in the tranquility of a certain sunlit room, I found something close, and it was more than I could have hoped for. I loved this time so effortlessly and entirely: it was sweet, and it was clairvoyant, and it should not have ended so soon. Truly, I did not want it to. I still do not want it to. I wish I could have stayed just a little while longer in the sanctuary of those four walls, where I was desired and unafraid.

But there is no place for me there anymore, because the waking world intervened. It turned that sanctuary into just another facet of my perverse effort towards self-portraiture, condemned to fade with the chemical tinges of winter. I thought that I could trust the pleasure I derived, when the night fell softly and we moved into it as one, but now even the gentlest of these engagements recall nightmares of my abandonment. No two living beings can exist indefinitely, together and untouched; and so once again, I am watching something die, something that I cared for, and I am powerless to save it.

I cannot sustain tender, or gentle, or vulnerable things. I am too violent, too defective. I burn with spectacular precision, but I cannot live simply or decently. I am not getting older: just growing weary of watching the same cycles take newer forms. The sheer repetition, elation followed by despondency, hardly hurts at all anymore. I know that something left my life, but I do not understand when or why. So maybe I truly am deficient, maybe I always was. I am passionate but infertile, and when things fall apart, I cannot stop them. In fact, I often wonder if I deconstruct them myself. And what does it matter anyways, this time around? This is not new to me: it will never be new to anyone whose countenance is desirable only in its abstraction. Fissures appear, the glamour fades. I have lost beautiful things before now, and I will lose this too.

I am everyone and no one, always running, always remembering, always trying so hard not to want to die anymore. I have to keep moving: I cannot ever stop. My Tiresian soul carves patterns in the fabric of the world, shapes the currents of negative space wherein my consciousness sears with its own differentiation. Vanity, self-loathing, and fascination imbue all of the people that I am or have been—the withdrawn woman with shorn hair and faraway eyes, retreating always towards an empty doorframe; the reverential lover of those bright and shining forms, wielding elation like a knife’s edge and leaving her image in their skin; the jaded user who medicates each memory, drowning her indifferent soul in chemical tides; the restless adolescent with open wounds and a mind like a broken mirror; the cynical young man smoking cigarettes on London streets; the debased artist closer to laughter than confession; the radical dreaming of a different world; the lost little girl who still cannot quite understand where her father has gone, or why.

I have spent so much of my own existence wistfully mimicking tenderness, affection, vulnerability, gratitude. I socially perform paradigms of loving when I am often too tired to feel anything at all. And yet, I am not fully spent, because there have always been those who will not lose or leave me. They keep me here when nothing can; they call me by name when I fall beyond language, and so call me back to myself. When I am withdrawn or withdrawing, they lie patiently by my side, trusting me to resurrect myself again and again, knowing that I am doing everything that I can to make my way back to them. Perhaps this is one of those times; perhaps I have merely wandered too far from those who know me, in the mists of my somnambulist state. But I am awake now, I can feel it—and I will find them again. I will find them.

My desperation ebbs like a pulse. I used to be so much stronger, but I am tired now: I am tired, I am tired, and I wish to feel nothing at all. All I want anymore is to love, to be loved, to engage. I want to be like a child again, immersed in that sense of abandon that I only achieve when that thing that lies dead or dying in my mind is rekindled, and breathes inside of me. I want to believe that I can care and be cared for, that I am known and valued, that I do not have to be afraid. I harbor an unspoken desire to be unnoticed and overlooked: to harm no one and eventually fade away. It is the yearning of the child I was never allowed to be: to keep so quiet that no one can never find me. But my nostalgia is futile, and I mourn for a past that is not mine. I am growing so weary of solitude and self-protection. I am ready to feel some other way.

My mind is tangled in bloodstains and bed sheets: in the refuge of a nameless language and the longings of a body altered long past recognition. Even after all of these years, there are parts of me that are not getting better. This is not a meditation: it is a confessional verse. Whatever I may write or say, always remember that people like me were never meant to survive.

So what in the world does it mean for us when we do?

I knew a girl in childhood who, when I was still young enough to believe in my father, was already infected with the history of this world. In the final conversation we shared, as we lay in the afternoon light, our silence was flooded with formless expression: the ever-present thoughts to which we never gave a name.

I am with you. I love you. More than my life, and always, always—

Her head fell sighing back upon the white fabric, among the drops of blood that framed her mouth like garnets, beautiful and clean. Gazing at me, one unclenched hand resting by her face, she placed her wrist beneath my fingertips, and let her eyelids fall. Then I could feel everything she was, running like memory through those ephemeral veins, and I knew the last dream of my childhood: to never love again.

There will be time to murder and create.

T.S. Eliot, The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock

I found you in the edges of some long-forgotten calamity, in the respite of my solitude, in the hunting call of winter. I still remember the night you came into my life; you had shadows under your eyes and a voice like tinted glass. I had been cynical and listless and tired as all hell, and you made me feel new, like the morning. But I was reckless, when I should have been wary. I cared deeply, when I should have felt nothing at all. That will be the tragedy to destroy our aimless days: what I mistook for love was nothing more than the reflection of a formless vanity, an irredeemable exercise in the practice of self-gratification. Our tenderness dims now into a delirium of unfinished thoughts and half-remembered sentiments. In the mournful present of this fading exaltation, I have nothing left to give.

Are you reluctant now to live like this, to descend further into the chaos of a liminal existence at my side? I know a rapid, caustic love that breathes away beneath my reason, tasting faintly of an abandonment that I may never exorcise. It festers and compels my form, like a richness in the soil: can you feel this darkness, when you move in me? Is it why you draw back, then closer, imitating tenderness, when we both desire to tear skin back with gleaming teeth and bare our subtle bones? What madness have you kindled in the refuge of my intrigue, and why you, why now? You know I never wanted this—so forgive me, Eurydice, if I cannot meet your gaze.

E quindi uscimmo a riveder le stele. Witness your expulsion from my fury and form: your normalcy, your mortality, all the strange and sensual yearnings of the body you destroy, your own. You were a long-term causality, you were a slowly unwinding catastrophe. I exhale your savage radiance like a constellation; oh, you feral thing.

I will be there when the floods roll back, when celestial light rains down in landslides and sanctifies this living earth in tides of midday fire. On the shorelines of Tragedy, that Janus-faced collapsing of time, I will remain and recall this lost potentiality, the stillborn adoration that died before taking form. As it waned, it left me barren, and neither the earth nor I can now sustain what our ravaged countenances crave. This, of all inane things, is my inherent sin: I could not keep her, or my memories, or this love alive. I am not fertile, I am not whole. My empathy is not a virtue, but a willful tendency towards self-mutilation. I am deficient. I am empty. I allow things to die.

In the volatile fervor of a physical existence, allegory invariably falls short; you and I evoke a wasteland that has yet to come into being. Desecrate or find me there, in the chemical currents of that which could consume you, for we have destroyed each other as surely as we have destroyed ourselves. In what light remains, I glimpse her preternatural form: that strange, seraphic figure, lamenting and exalting as the mutilated world moves silently towards decay. I recall her from childhood, in reluctant fingers turning the pages of my mother’s Bible, Isaiah 14:12—And how you have fallen from heaven, morning star, child of the dawn! In the narcotic-dimmed haze of my first dying, I knew the violence in those eyes, the hair cropped short in locks of silver, the saturnine wings unfolding from the notches in her spine. Alone now, she unwillingly endures; and the world will suffer the torment of looking upon her, somnambulist and wretched thing, wandering that desolation in search of a better self. Even you will know then, for all your pride and carelessness, how I came to live like this.

Every woman was born to wrest stars from their galaxies, to grapple with the voiceless language that floods the ruptures of physical sensation, when ecstasy moves through the body’s breathing core, and the world speaks to itself in paradigms of music. I more than most, in the still-living darkness of my sanity and soul, have been birthed for this purpose. I occupy that liminal positionality between the tangible and the untrue, my memory colored by the fantasies and phobias of a thousand other minds. A sentient lucidity moves through my androgyny and my desires, carving the space for a nameless gender.

Two years ago, the waking spring told different stories of this same conscience. Even now, I cannot write or speak plainly of that time: it is too shameful, too obscene. When I lost her, that second self, I lost all will to suffer on. I thought that this mind, and all that it is capable of, would die there, on some shit couch, in some shit apartment, and I simply did not care. But when the fourth morning dawned, its pale light found me upright, enduring, alive. I had waited for my grief to end, and it had not. Do not mistake me: this was not an epiphany, not a rebirth. It was resignation to living another day. It was, in some ways, unforgivable surrender. I was too dead even to die.

So I turned from what was left of it, that life I used to love: I stopped striving for pleasure and learned to appreciate feeling anything at all. It was then, on the streets of London, that I found her. She stood before me, grinning wryly in the shadow of the city, and I experienced a sensation that I could never hope to name—something fierce, like defiance, and something rapturous, like joy. I knew then what I should have known all along: that no trivial circumstance of the social world, no meaningless extent of its sanctimony or its cruelty, could have undone so extraordinary a mind. How arrogant I had been, how misguided, to imagine that I alone could crawl from a self-appointed grave. Denied the tenderness and the solace that I owed her, she had nevertheless endured. I had betrayed her utterly, I had failed her unforgivably; and still she had come back to me, and she was altered, but alive.

We spent six hours in a dimly lit bar. Soporific elation whispered up and down my form, and in the revenant consequences of a shared history of self-destruction, we met one another once more. A part of us had died with bygone days: we both felt this irrevocable absence, both mourned for that which we could not change. But we spoke on in spite of this, exchanging admissions of pleasure and penance; we resurrected the world of our collective past, and all of the memories, sweet and unspeakable, which we had so wrongly believed would be better off forgotten. Until my mind fails me entirely, and perhaps even then, I will remember that night. She seemed to be more than human and far from divine; not angelic, of course, for she had always been too irreverent for such fragile categorization, but savage, sardonic, extraordinary. As the light threw shadows across her face, I could feel, like ink and cyanide, the chiaroscuro of this beautiful creature: and how natural it was, how fitting, to be one with her again. How easily I knew her mind—after all, it was mine.

The bus was silent and midnight had long since passed. From one sleeping city to the next, I rode with leaden eyelids and an opiate soul. The young man sitting behind me answered a ringing phone, and received, as I could perceive it, the news of a woman’s death. He had loved her, at some time and in some way: I could it hear it in the way his voice broke, running like a wrist across the edge of each shattered word. That man bled as he spoke, and I watched his life change before my clouded eyes. In my narcotized state, I felt his sobs move like ocean currents through my mind. Compelled to preserve the strangeness and sorrow of the scene, I made as though to write, but could form only a single phrase, which echoed incessantly as I lapsed in and out of consciousness—I bear witness. I bear witness.

I was a voyeur to tragedy, in that night torn mad with a thousand turns of circumstance; and although some secret part of me felt deeply for him, it was more than I could communicate or understand. So it was her that I ultimately thought of, the catastrophe that almost was, flooding my exhausted memory in the garlands of white roses that framed her sightless eyes. Foremost among my racing thoughts was the question so simple and so very strange—how can a body die? And why couldn’t ours, when we wanted them to?

Sometimes I wonder at my own inane existence. Would I be another Lazarus, incomparably versed in the art of impermanent demise? I catch my reflection in each window that I pass: lithe and emaciated in my Orphean state, I can see the subtle movement of each bone beneath my skin. Every time I lose myself in these bouts of paranoia, someone inevitably offers mundane consolation: You will survive this. But perhaps I do not want to survive. I have been surviving all my life. Perhaps I am ready for something else, anything else, something more than survival. After all of these years, I am nourishing myself still.

So if ever I was thoughtless, or distant, or withdrawn, please know that I never chose to be. I will always remember you fondly—those nights of shared cigarettes and unending conversations, your unconscious earnestness and quickness to laugh, how strange and sweet it felt to finally kiss you on the corner of that silent street. My mind retreats often to half-imagined visions of the history we have shared: I can still recall those inimitable rushes of fondness and fascination that flooded this body on clandestine evenings, as I knelt among the rattlesnakes that fell around your feet.

But in some ways you are so very like me; you are suffering, you are not whole. On a bridge above the nighttime currents of the Thames, for a handful of five-pound notes and a few quiet words, you gave me consecration in its chemical form: that folded piece of paper, so small and nondescript, that would undo us both in time. You ran your hands through my shaved hair, along the lines of dark ink that moved across my skin like the waters below us, and I became exquisitely aware of my own living form: shorn and scarred and still so beautiful. In some ways, I think I always knew you. I think you have always wanted to be known.

But I cannot remain in stasis any longer; I cannot cheapen my existence, cannot limit the potential of this body and its longings. Just the other evening, I came to learn the language of yet another form that was not yours, watching and loving the helplessness of his pleasure as I manifested quiet, coiled desires upon his skin. I made myself alive again in each rapid breath he drew, in the mouth that moved beneath the tips of my fingers, in the rose-damp parting of my thighs. Too often, we define such acts in terms of penetration, but this is the fallacy of a misinformed world. The experience is one of envelopment, of consumption: not an entering, but a taking in. With violent affection, I took him apart with my teeth, decided to suffer so that I might heal—and how wonderful it was, to feel those muscles move again. As the sun began to rise, I lay entwined in his limbs and waited for the morning. A cold light fell across the bruises on his neck, running down over the lovely shoulders, where my mouth had left impressions in the skin.

This is how it always begins. I have a beautiful, damning habit of loving many people—loving them deeply, ardently, differently, and all at once. Even now, I have not forgotten you. There are still so many ways in which I wish to know you, so many questions I never thought to ask. Are you lonely in the winter? Are you afraid to die? Perhaps, in time, you will overcome what has happened to you, and awake on some far-off morning to find that you are whole and strong and ready to try again. And if this should come to pass, then I hope you will return to me, no matter the place or time. You have suffered enough, my love, and so have I; but this existence is cyclical, and I am never hard to find. So if you ever heal, come back to me. Perhaps I will still be waiting.

Oh, indifferent soul, how I could have loved you. Maybe there is still reason to try. Maybe this doubt will fade with the winter. Maybe you have yet the time and tenderness to unearth the obscured, lovely parts of me, to make me clean again.

But it is too late, I am afraid. I am not blameless anymore. I do not have ambitions. I do not have ideals. I live for those evenings of rushing pleasure, when this body is roused like a rainstorm and I feel real again. I am moving towards a willful apathy, so that when the time comes I might look readily upon the falling world. It is better this way. So allow me to take leave of this, to live indifferently on—and until the night comes howling, may I never write of you again.

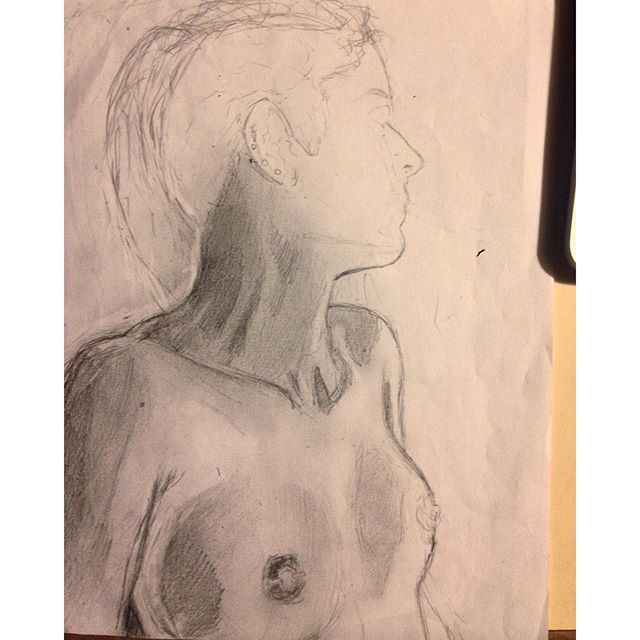

charcoal and #2 pencil. january 3, 2016. (unfinished).

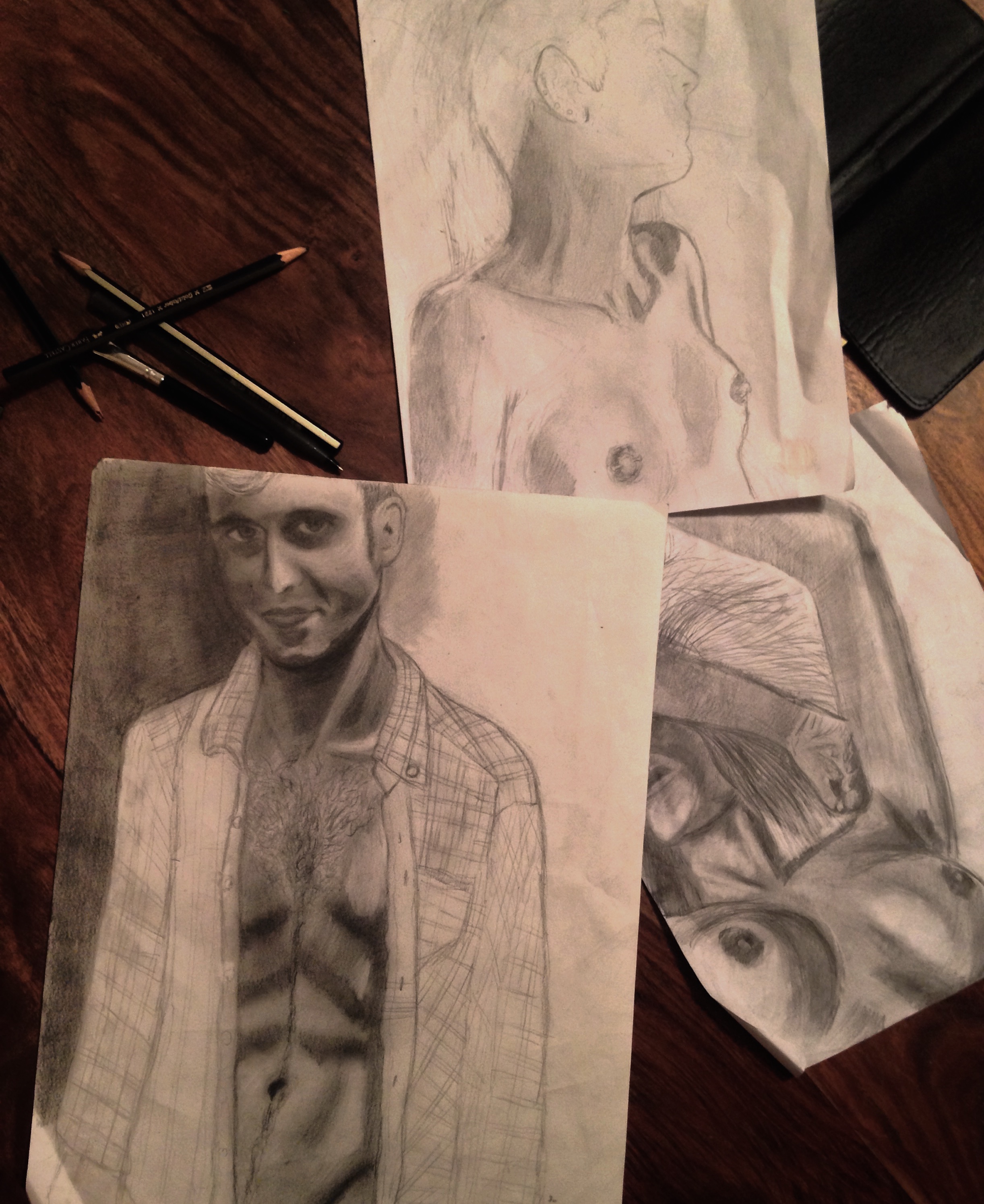

just an update on a few of the pieces I have been working on

A Feminist Narrative in 14 Parts

For my mother, who knows who she is.

Alison Bechdel, Are You My Mother?

I recently had the pleasure of working with Corinne Singer and Maggie Kobelski on Corinne’s ongoing series in feminist self-portraiture. The first installment, entitled “Mother, May I?,” came into being in late December when, at the seaside town where I once spent my childhood summers, I walked into the Atlantic Ocean wearing my mother’s wedding gown.

For as long as I can remember, it has simply been expected that I would marry in that dress; but following the deterioration of my parents’ relationship, my struggles with mental illness, and my efforts to come to terms with my own sexual and gender identity, the oppressive implications of such an assumption took on violent significance. Always symbolic of conformity, by the time of the shoot my mother’s wedding dress had become a representative site upon which the traumas of my adolescence—the toxic constraints of heteronormativity, the lingering anxiety of disappointing my mother through my unconventional state of being—were made manifest.

In some ways, “Mother, May I?” functions as a visual counterpart to “Love and Other Theories of Subjugation,” wherein I describe an allegorical scene of submission in (and to) the waters of the Atlantic, reflecting upon my own psychological need for respite. In other ways, it was a challenge to my own body: kneeling in ivory satin among frigid water was a means through which I could explore my own physical limitations, and in doing so, engage in an incomplete (but perhaps not entirely futile) effort towards transcendence. In the latter regard, the entire endeavor can potentially be read as a reflexive, even masochistic act; more than anything, though, it was the visual extension of my understanding of the human body as an intimate site of desire and revolution.

The conceptualization of this piece drew heavily upon the feminist tenants of physical reclamation. My status as a neurodivergent, differently abled queer person with a complex identity that includes ‘woman’ is visually and thematically evoked in the lines of Sapphic poetry painted onto my body: the characters along my collarbone read, “Someone, I say, will remember us, in another time,” while “Hymn to Aphrodite” extends across my back and shoulders.

Efforts at self-portraiture are complicated by the many facets of my identity that cannot be reconciled. With regards to the trajectory of the photographic narrative, however, the themes that come immediately to mind are captivity and sacrifice, abandonment and solitude, violence and desire, sensuality and subjugation, shame and self-medication, resistance and liberation, baptism and rebirth. In my artwork and my writing, I have rarely achieved the sense of catharsis that I experienced when modeling for this piece.

This narrative is dedicated to my parents, my queerness, my body, my resistance. It is dedicated, in short, to the willful destruction of beautiful things.

1. Surrounded by containers of makeup, clad from the waist down in my mother’s white dress, I face a mirror imbued with my form. Although it was originally intended as a test shot, I begin to view this photograph, the first in the series, with uncertainty, and then fascination. It is transfixing to gaze upon my own image, twice framed: so strange to see myself unintentionally misrepresented as a lovely and feminine thing. Sunlight filters through the windowpanes, soft against bare skin: gradients of shadow, beautiful and subtle, adorn the folds of fabric. In this effort towards self-portraiture, I am the object of my own contemplation: the project begins, as it likely should, with the ongoing question of my gender, and a conscious performance of the self.

2. Kneeling in the sand for our carefully constructed evocations of traditional wedding photographs, the first thing I am conscious of is being colder than I could have imagined. The diaphanous fabric of the veil is cast away from my face, revealing an incongruous joining of propriety and discomposure. The dress, which encompassed my mother’s form so gracefully when she was only 25, is too large for me: reams of white satin drape awkwardly over an angular frame emaciated from cigarettes, sleepless nights, and too many other mediums of self-consumption. Tendrils of dark hair are not quite enough to cover the shaved and tattooed side of my head. My eyes are shadowed, deep-set; my skin is scarred and pale; my lips are ashen, almost anemic; my countenance echoes the muted tones of the landscape surrounding me.

3. These are the photographs that my mother dreamed of someday seeing when she gave birth to me, her only daughter. But like the dress itself, they do not fit: they are unsettling, dissonant. Discontent textures each image: the specter of a captivity that has haunted me since childhood, informing my longings and impeding all efforts towards resistance. I emanate a stark sense of discomfort with the parameters of my sociocultural existence; is this is the only permissible way for my body to fill the space around it, as the object of another’s gaze?

4. I cannot be adequately represented, or even contained, by those sterile, bloodless images of a woman that I am not. So as the daylight begins to fade, we focus increasingly upon the boundaries associated with gendered and sexual conventions, and the instability of desire that such margins ascribe. The tide advances: I move towards it. The veil is disposed of; the shaved hair, the many piercings, and the dark ink become visible along my skin. No further effort is made to keep the dress from slipping off of my tensed shoulders as I crouch like an animal, anointing my face with water and marring it with sand. Makeup runs in dark rivulets, and my hands clench and claw at the earth, craving a nameless liberty. I am abject and full of rage. Rage for my mother’s abandonment, rage for my own psychological mutilation, rage for those years of self-loathing that gnawed away at my sanity until they made me what I am. My entire body reacts against the fact that I was given so little say in what I would be expected to suffer and survive as a woman, as queer, as fatherless, as alive.

5. These recollections inspire a natural, almost involuntary defiance: inspired by Yoko Ono’s “Cut Piece” and its connotations of sociosexuaul violence, we tear away at the fabric of the dress, mangling gossamer sleeves, exposing bare skin, smearing wet sand across the intricate lace bodice. These willful acts of destruction constitute, for me, a rejection of the imposed existence that I accepted for too long; but no act of violence towards my half-remembered history can alleviate the isolation of the present. A vast expanse of water, smoother than glass, serves as yet another mirror in which to survey my own solitude: nowhere is it clearer how damningly alone I am, even as the subject of my own narrative.

6. My reflexive response to the most isolating moment of the shoot is the immediate assumption of a more sensual pose: within misremembered paradigms of sexuality and subjugation, I seek solace from “my grief and maddening solitude.” The impulsive motion is simultaneously masochistic and liberating—what better respite from the brutal senselessness of this existence, than a reckless and ongoing engagement with the selfsame acts of desire and decision that every known standard of gendered propriety has attempted to exert from my still-breathing form? Skin exposed, body rigid with the cold, I kneel in the shallow waters, gripping my heels with my hands…

7. … and then wrap my arms about myself defensively. Desire followed by vulnerability, longings complicated by half-realized fears, there is something almost fragile in how thin I appear, enshrouded in the dissembled silk that floods around me in tides of white.

8. Something close to beauty, utterly strange and distinctly sorrowful, emerges from these positions of imprecise susceptibility. Kneeling upright among the currents, I evoke, almost unconsciously, a sort of seraphic imagery: “aurochs and angels, the secret of durable pigments…the refuge of art,” in the words that Nabokov wrote, which imbued me with melancholy so many times over, leaving their impressions in the contours of my memory and soul. My posturing is both natural and dimly mythological: recalling violence and self-preservation.

9. Fingers numbed, it is nearly impossible to light a cigarette—but I know that if anyone can do it, I can. The act itself illuminates my bizarre, precarious relationship to smoking and social shame: the stigmatized practice of self-medication that has come to inform, and even characterize, my identity in so many relevant ways.

10. In my dissonant conflicts with “this slowly dying body,” smoking is a habit I engage in because it allows me to remain as sane as I am capable of feeling; it is an addiction born of trauma, which has nevertheless become entirely my own. I can claim each breath I draw, and feel no shame for the choices I have made, even as they consume me. There is, after all, a certain absurdity to the thought of a world that has nearly killed me in so many different ways, chastising me for something so inconsequential. For me, for now, smoking is an act of strength and resistance: it is a reaction to the culture that reprimands self-medication without paying mind to its origins or the consequences of its absence. After all of the ways in which I have been damaged or undone, this, at last, is an action I can inflict upon myself.

11. By the time the cigarette has consumed itself, burning away into ash, I evoke a very different image from the subdued girl with the fading roses and downcast eyes. Intrepid and irreverent, my resistance has carved a space for my androgyny, my sexuality, my multifold and semi-performative identity. The dress has been destroyed beyond repair, leaving no means of going back, of mending whatever damage has been done to that beautiful white fabric. I have torn it from my own body, and am occupying my surroundings now as more than an object of desire or aestheticism. I am too cold to feel my own skin, but the rhythm of my pulse is more realized than ever. My eyes are burning, framed in black; my hair is disheveled; the protective lines of Sapphic language have washed away, leaving only my bare skin and its many strange desires. There is a primitive, almost feral element to my defiance.

12. Despite all of my frustration and retroactive grief, it is a mournful and lovely thing, to lay waste to the dress my mother thought to see me married in. The gown is still beautiful, even in its ruined state, as I kneel beneath the luster of these radiant skies. It feels like a baptism, to immerse wholly in the currents, to reckon unflinchingly with the girl I was, the person I am, whatever I have yet to become. In some wonderful sense, it is the inimitable extension of that longing I have expressed so many times before, to leave “my life and my name and my consciousness in the keeping of those waters… to know that there is someplace left to lose myself.” Is this what it feels like to finally begin to heal?

13. Maybe—but then again, maybe not. After all, despite whatever language and meaning I impose upon it, the story the fabric tells is simple. I need a new beginning. I think I always will. So on the shorelines of my childhood, and in the object of my eternal fascination, the sea, I try for the next best thing.

14. Amid those timeless waters, I evoke the sensation of being reborn.

We have to consciously study how to be tender with each other until it becomes a habit.

Audre Lorde, Sister Outsider

Every time I bleed myself out in front of a blank page or a computer screen, I am reminded that it is damn near impossible to communicate fully, to forge the connections and the intimacy that I crave, when writing so directly and consistently about myself. But I continue to do so, for now at least, because for all of my confusion and my restlessness, I am something that I know. There are worse things to write about than that, I suppose.

Ghosts of my past reemerge with the dawning year. There are bones that I never put to rest, and people I could not keep alive; yes, that beautiful girl died, with white roses in her hair and eyes, but it was not entirely a tragedy. People change, after all, and what of it? If you do not know what I am writing about now, it is because you were never intended to understand. But for the briefest instant in our burning worlds, she was mine, and I was hers. That will always be true, it could never be anything else. What more can I really care to know?

How long do resolutions last? I am impractical, but not entirely naïve. I understand that a turned page in a marked calendar bears no real significance. I have never had the constancy or the resolve to keep the commitments I devise; but I will make my promises, all the same.

In 2016, I will remember, always, the treachery of pleasure: the unspoken wariness of anyone whose love, for as long as they can remember, has been mingled with trauma and directionless sorrow. I will remember that I am a body in need of protection, and that this is a beautiful thing. I will remember to stop projecting my fierce and nameless needs onto sites of imposition, be they desirous figures or gentle minds. I will remember to find secret, tender parts of myself and keep them very safe: to give less love where it is not wanted, and so carve out a space for myself in the world.

In 2016, I will find more spheres of women, queers, and people with complex identities that may include “woman.” These communities love deeply. I want and need to be cared for in that way. I will touch and be touched, I will write and remember; I engage in these acts already, but I will try to spend less time fretting over inevitable endings. Perhaps this is the first step towards finding a kind of love that does not devour me, towards knowing the value of my life and mind.

In 2016, I will live fiercely. Where I walk, I will strive to be remembered. With passion and precision, I will fall in love with what I am. I want to be adored: I want to suffer and survive until no one doubts that my resistance is also liberation, and that I am the the better for it. When I lose myself within a labyrinth of my own conflicted desires, as I always eventually do, I will be more and less than Icarus, still alive, still in flight, and burning, burning, burning; they will call my name on raucous evenings, and remember me on city streets when the night is gone.

As I write this, I am filled with a quiet joy. The ocean breathes, thirty feet below me. The stars blaze softly. This, right now, is one of those moments when I am really present. There are no barriers, no secrets, no lies left to tell. I am not distant. I am not guarded. I am whole. It does not matter if I keep these resolutions, because I have written them, and so have willed them into some sort of existence.

Maybe if I reckon with my pain instead of avoiding it, I will have nothing left to be afraid of. I know that I cannot have everything, but if I can create so much, and feel so deeply— even if I cannot necessarily survive it—then maybe I can start to make some sense of this inane world.

I will move slowly and determinedly towards a more harmonious state of being. The entire endeavor is cyclical, of course; I will inevitably become bored again, live within those psychological extremes that most people will never know, and when my mind and body have sufficiently consumed one another, I will ease myself out of insanity and adjust once more to the rational world. Maybe some part of me simply does not want to be sane; maybe that is why I am so incredibly inept when it comes to healing. But the present task is simple, an effort towards stability. I want to believe that I am capable of that.

I will try to remind myself that, in instances of loss, I am not always entirely at fault. My world changes, I grow older: the person remains, but the feeling they inspired fades to memory, and then to nothing at all. So I will refrain from crucifying myself, over and over again, on the transience and the tragedy of those pleading words—I need you to just hold on, until I am sane enough to love you again.

Am I really so alone? The only one grieving gently, the only one who retreats from the indifferent cold of an empty bed on sleepless nights? The only one who tires, at times, of being so deeply alive? Surely, somewhere, there is someone just as conflicted and impassioned and flawed as I am. Could we teach one another to feel more completely? Could we heal whatever mutual wounds our histories have inflicted? Could they make me feel safe again? Could they tell me who I am?

I will always be strange and I will always be displaced, because so much of my existence is determined by the perception and conclusions of a thousand other minds—such is the tragedy of the social world. But that is not so terrible: I can withstand the voyeuristic impulses of the culture I engage with, I can survive the stigmatization that I learned, in my early adolescence, to simply expect. And I can do so alone, if I have to.

Let me remember this moment. I love to know that I can feel this way. It is so rare and so strange, that I should exist and be heard. I am not sure who or what I am writing for now: lovers or strangers, confidants or companions, the woman I eulogized or the self I have yet to fully understand. But I will not apologize for this most recent engagement with the language of my own mind, however discursive or self-indulgent it may seem. I will not waste another year killing myself off for the respect of an audience that hardly exists. I will be different, and I will be better, for as long as I have the strength. I will write, and feel, and love, and burn, until there is nothing left to save.

Oh, my love, take me there.

Let me dwell where you are.

I am already nothing.

I am already burning.Sophocles, Electra

Mild December mornings find me listless and on edge, smoking cigarettes and drinking weak coffee in New York’s East Village. Listening to shit jukebox pop songs, avoiding street cabs and strangers’ eyes, I adjust to the insincerity of the city, immersed all the while in the dim paranoia that colors the wary reintegration of an insomniac into the waking world.

There are always days or weeks or months, impermanent instances wherein I begin to wonder whether or not I have lost my mind. Every time, I worry that I will not recover, that maybe this time, it is for real. And there is a certain joy in the reckless interest with which I navigate these temporary bouts of instability—cynical and strangely high-spirited, quick to laugh and slow to focus, I live like an exposed nerve: vulnerable, feeling everything.

I am always between worlds, haunted by that selfsame specter of displacement that strays through each new city at my side. I long for home, return to realize that it was never truly there to begin with, that it left with my sanity and my father on a cold grey morning so many years ago. It seems like a lifetime now. I spend holidays reliving each whiskey-dimmed wandering down the silent streets of England, dreaming of that directionless respite where my second life lies.

Just the other day, I decided that I had witnessed enough, and drove two hours north down a narrow highway until I reached an empty town at the edge of the Atlantic. There, a friend and I watched beneath saturnine skies as the ocean heaved against wind-chilled shorelines. We spoke in misremembered lines of poetry, for we had no language of our own with which we might express the enigmatic beauty of those waters on a moonless night. Our recitations perforated the silence, each word rewriting the margins of measurable time, and we returned home again in a haze of joyful abandon: smoking cigarettes, driving too fast, shouting the lyrics to old rock songs as they rang from a broken-down radio. Sometimes you have nights like those, and you understand that it is not so very terrible to live, to think, to feel. You remember that you have the constancy and love to form relationships that endure. You find solace within, and in spite of, a world that offers none. You live on, and on, and on.

I realize now that I may well be within the sensual bloom of my own existence. Am I entering it? Is it waning? I attribute my sexuality, my singular and self-contradictory identity, in large part to the fact that I am practically crawling out of my skin with fascination for the bodies of others. I do not accept the politics of compulsory heterosexuality. I am too passionate, too sensuous, too curious, too undone: I refuse to limit my experiences to any one gender. I want to be young and half-mad with desire forever. Live fast, die pretty—right? But I do not want to die at all. Not anymore, at least.

But there are times, I must admit, when I feel exhausted. Is it possible to reckon wholly with the impulsive passion of our own histories, without inevitably feeling older than we are? It would not be so tiresome, if I could only see these dimming years as inconsequential: if I could allow past lives, and loves, and losses to fade away into obscurity. But I have never known how to lie to myself.

Sometimes it simply does not work. Sorrows that are the most insurmountable, the most exquisitely damning, are always conflicts of positionality. Sometimes someone gives you everything they have to offer, and it still is not enough. The timing is wrong, your body is wrong, you need something that no one could ever give to you, and it makes you so happy and so sad at the same time: because you know you are as content as you ever can be, and you realize that maybe you will always feel this way, and you wonder why life at its best is so sweet but so sorrowful. It might sound pretentious, or even maudlin, but there it is. Perhaps in moments of melancholic stasis, we catch glimpses of who we are.

So how can you explain to those that love you, that remembering them is more difficult than catching smoke between your fingers? Nothing is sacred, not anymore. Every time I start again, another person, another place, it always ends with the same banal sentiments: I want you to know that I really did love you. That I really did try. Self-preservation becomes its own peculiar form of cannibalization: I lend my mind to intrigued strangers, and forget them all just as easily. How on earth could I have allowed myself to become this way?

In those rare moments when I am fully present, I find a peculiar comfort in feeling deeply: in eclipsing all that the other has to give. How many times have I lived over that stripped down bedroom scene, enthralled by the very futility of our efforts? Two uncertain strangers, wide-eyed, afraid of our own bodies’ desires, sharing nothing except a sense of fascination: intrigued by one another, by ourselves. Satiating nameless needs, engaging roughly in acts of tenderness: I will always remember the sweet and violent words you spoke, in the blush of that fast-approaching morning, when I found myself at your feet. You asked me to stay, pushing tendrils of hair out of my eyes: and what a choice I made that night—you still do not know the courage and carelessness it took.

In the weeks that followed, I dreamed vividly of a strange and hallowed place. There were garlands of asphodel in juniper branches, and mirrors imbued with prismatic light. You were there with me: you were nowhere else. When you spoke, you did so in gentle words tinged inexplicably with remorse. I understood you then, as I never have before or since; your clandestine yearnings, your hushed apologies as you took my fingers in your mouth. I felt the rhythm of your throat, those softly moving muscles that make your voice so low and sweet, and the strangest longing blurred my vision as from above you I glanced down. I wanted to inhale your waking consciousness in my memory and flesh, as your abandon breathed dimly through the twilight of my stirring form, submitting to my impulses, subverting what we understand to be the natural language of our desires. A silent pleasure nearly deafened me when your mouth moved in mine; I could know greater joy than the murmur of your heart beneath my hands.

How lucky I am to have found, in this absurd existence, such wonderful ways of passing the unwanted time.

Do not misunderstand me: I no longer have the patience for imprecise, diluted love. That is the best you could offer, I think, and so this feeing of mine is merely fascination, infused though it may be with tenderness and a certain sorrowful pleasure. Do I know you? No, of course not: I never really desired to. But there are facets of being that evade your waking consciousness. I learn to understand what requires distance to be known.

An absence bleeds within and throughout you, coloring your countenance like memory running through a living mind. Once, and never since, you gave that absence form through the parameters of your susceptibility and the language of your grief, reminding me of one who, in another time and place, did the very same. Hers was the body from which I learned my love and limitations; is it so surprising, then, that I should react as I did? My mind met yours in a flurry of misrecognition: that was the moment when I decided not to care about practicality or consequence, decided to survive whatever comes of this. That was the night I let you in.

I will not love you, but I like to know that I can; and that I would heal you, if I could. I give this potentiality less threatening form through a sort of detached curiosity: could I bring a person such ecstasy, evoke such adoration, that they never wanted to leave? It may seem callous, but I have been left all my life. I seek respite in these urges, but they manifest, at times, in fixation, and I simply cannot allow that. I have too much to think of, too many things to create.

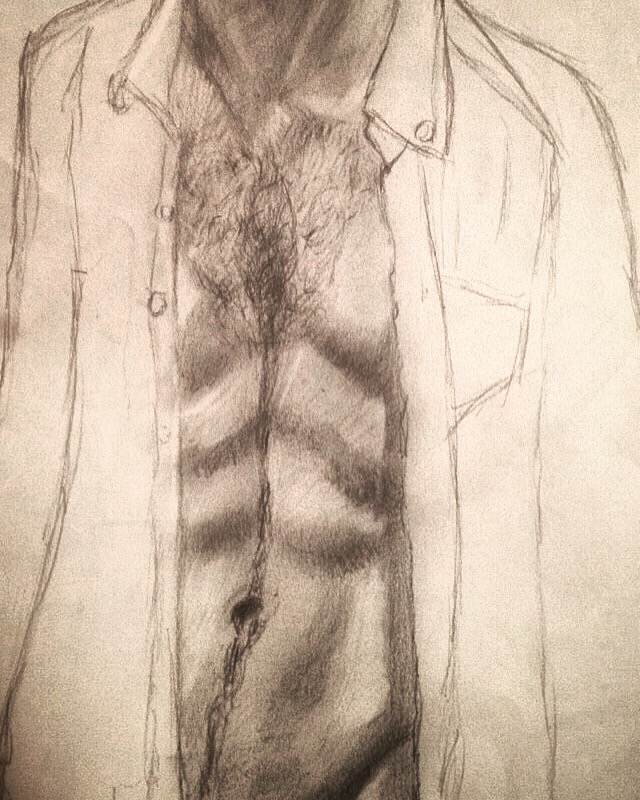

So I turned once more, in your case, to the confines of my mind: I framed you within my gaze, false remembrance serving as my means of forgetting, and regarded the visual construction of your form as I might an exorcism. You bled from my hands onto the blank page, leaving stains of charcoal along my fingertips, my wrists, the skin on my forehead where I pushed the hair back into place. Everything I touched, I marred as though with ash.

I chose the wrong person again, I am afraid. I always do. But then, don’t we all? And what does it matter anyways, when a thousand forms and figures pass through my periphery? Even now, another soon-to-be memory strolls through Oxford shops and alleyways, evoking all of the opportunities I never took. In the morning, her name is everywhere: it floods my mind in a thousand strains of music, running like rain through the cobblestone streets.

So where do we go now, what do we do? This cannot last, so want me now, and I will do the rest. Abandon your inhibitions, silence your lingering doubts: I have never cared much for complexities of circumstance, and I am never hard to find. I will remember the good days, and forget whatever else I can. When I write too often, it all starts to feel the same. I knew you, my darling, I knew you, I loved you, and I will remember you. I will, I will, I will—will I? Will you? What a strange and terrible thought it is, that I may wake tomorrow feeling nothing at all.

But fuck that, fuck all of it—I have too much left to write about. I am alive now, and two years ago that is more than I ever could have hoped for. I write for myself now, because in this senseless reality, I am my own best subject. I refuse to be remorseful, to water down my own existence to some self-effacing apology. Why be selfless where you can be satisfied? Everyone is surviving something, after all, and I am not even sure what it really is that I write about now. My hands shake with a thousand unnamed longings, but I am not suffering, not anymore. I do not want to die: I burn and burn and burn. This is what I am now, this is where I stand. It is precarious, it is absurd—but I love it, all the same.

charcoal and #2 pencil. december 15, 2015. (unfinished).

I would like to tell her, Love

is enough, I would like to say,

Find shelter in another skin.Margaret Atwood, Selected Poems II: 1976-1986

You take my head in your steady palm, push me gently below the surface; oceanic waves envelop me. Of course I cannot breathe, but I submit so willingly, drown so blissfully, surrounded by the rhythms of the sea. Memory and motion, a slow-moving cadence, my mouth seeks solace in that clandestine hollow where your hips meet the inner curve of your thighs. All around me, perfect stillness: I can hear your sighs above the water.

I am a living thing. I have lungs, a pulse, please understand: I cannot always remain beneath the surface for so long. I could only ever lay waste to what I am, kneeling breathless at the bottom of the sea; and yet, to hear those sighing, shifting waves I might have stayed a lifetime longer. I might have submitted to the ebb and flow of desires that were not my own. I might have surrendered entirely the dignity of my being, left my life and my name and my consciousness in the keeping of those waters.

Know now, and always, that this would have been done not for your pleasure, but for my own deliverance. It was wonderful, just once, not to exercise ownership over my private self. To be simultaneously desirous and subdued. When I surrendered to that current, to those tides, I was released, if only for an instant, from all of my grief and maddening solitude, from the discordant history of this slowly dying body. I only existed where the waters touched me. I was simply the surface of my skin.

I frighten myself sometimes. For all of my violent impulses and narcissistic desires, I am still so very gentle: a raw and open wound. I do not think that I am suffering, but perhaps I have been this way for too long to be sure. When I awoke, there were bruises on my knees, and I knew that my own fingernails left those imprints on my heels. This was subjugation, reduction to a purpose, the nature of which did not satiate that nameless need for convalescence that I practice and retain. Even so, I welcomed it. I had nothing to fear because my self was mine to give. Because all the while, I could feel an ocean breathing beneath my skin; and have you ever known an ocean to be tamed?

I wish that it were not so easy to fall into such tired clichés. They do not lend form, or truth, or meaning to these hollow words. But still I must wonder if I am being drowned, or saved, or baptized. I must always long to have been taught whatever difference lies between love and degradation, must always wish that they need not be forever joined in my myopic eyes.

I want to know now what sweet and gentle things my soul is capable of, how many ways I can work myself inside of you, but with intentions, for once, wholly pure. I want to know how many ways I can bring ecstasy to another living being. This desire is more than physical. It is cerebral, rooted in the mind that has tormented and sustained me, in the desires and the decisions upon which I will likely die impaled. I have to know myself, whatever the cost. This is the choice that I made.

So if you ask me to stay, I will try to, for as long as I can feel this way, and as long as these melancholic pleasures still murmur across the shorelines of my skin. I will remain and remember the best of these uncertain days, awaiting the inevitable realization that your deficiencies are neither transcendent nor justified, that I can no longer misrecognize myself within the depths of your eyes. And when I find that I cannot go on, that this lie of ours has lost both its form and its meaning, then I will leave without pretending to understand why. I will return to my words and to my solitude, and my heart will forever know a quiet tenderness for those hands that brought me such joy as they ran, like light over water, along the length of my bared soul.

Soon I will remember that I am more than roses. That there is a world and a history written into the folds of my skin. That there is a language to my movements and desires, incoherent though they may have been rendered by the immutable absence of one capable of translation. This is the day you will lose me.

Broken, torn, tasted, I grow weary now of searching hands, of stripped and selfish love. I want to be unfolded, opened, turned back upon myself in reflexive ecstasy like the pages of the books I have loved so well since childhood. But I am afraid that I am no longer the same body that I once was; what knelt there among the restless waters, this fragile expanse of skin over bones, the abject eyes, the notches of my spine—that was not who I am, but what was done to me. My form has become prismatic, all vertebral ridges and geometric planes, wasting away towards nothingness (as are you, my dear), evoking its own masochistic history.

I want to know that there is someplace left to lose myself. I want to submit to these waters, toxic and timeless, and taste the salt and sacrifice of my willful subjugation. I want to feel your hands along the margins of my body, reminding me gently and irrevocably of how very alive I am.

I am tired. I am so, so tired. It is never anyone’s fault when I begin to feel this way. This is the longing that lies at the heart of my ecstasy as well as my grief, texturing my writing, my loving, and all of the directionless longing in this self-consuming mind. I need something that no one could ever give to me; there is not a body in the world that can shelter me now, not even my own.

Perhaps it would not be so terrible, then, to give myself up entirely; to limit this mercurial existence to whatever pleasures my body can provide. Is it really so different, after all, from the decision I made two years ago, in becoming an organ donor?

So someday, please, if the time has come and you still remember this, make sure they take whatever they can from me; whatever is useful, whatever brings peace. The lungs will be worthless, but there may be something left for this body to give. As for the rest, bury it at sea. Do not hesitate, do not delay. I will be ready then, I promise you, to look upon the Atlantic once more.

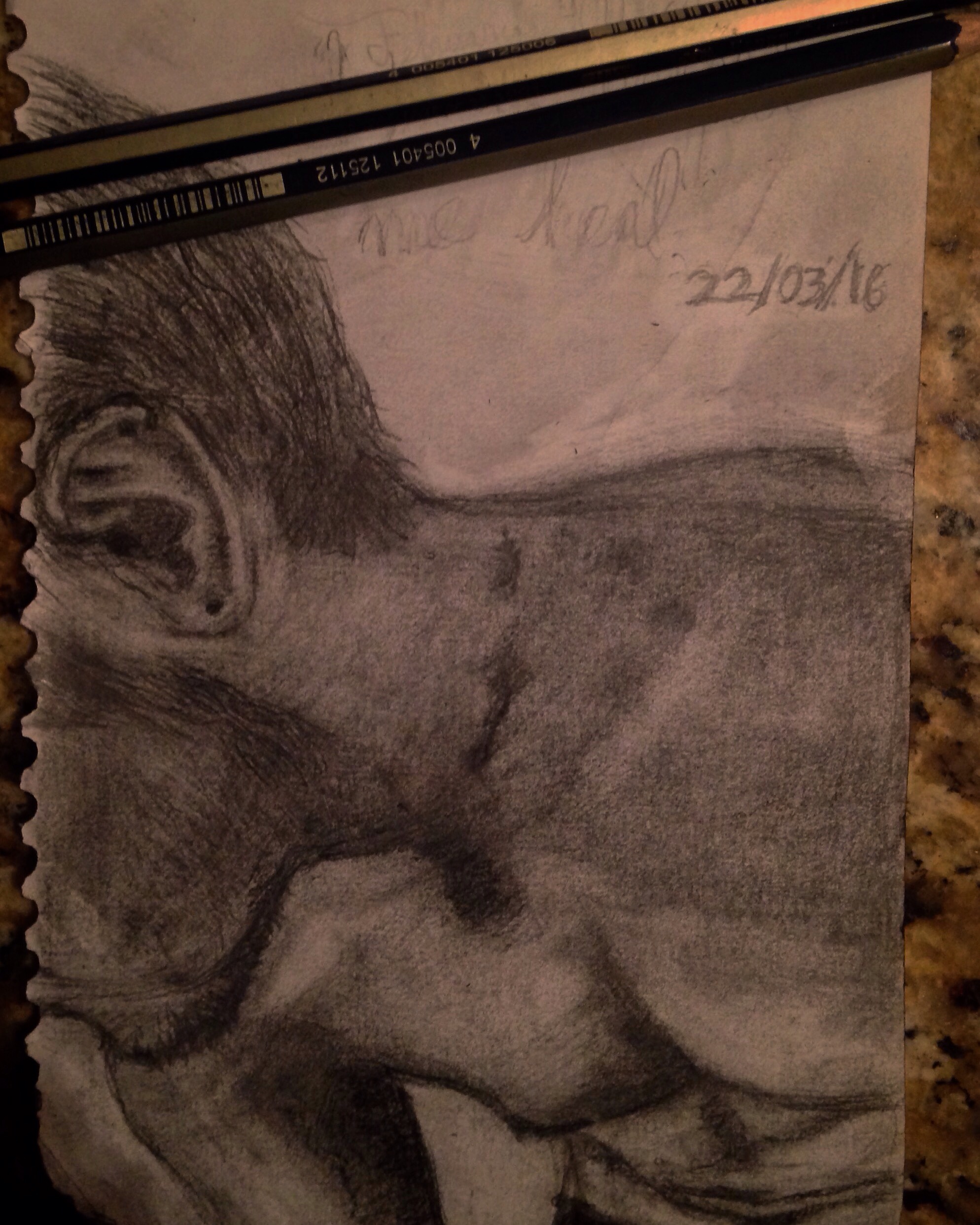

charcoal and #2 pencil. november, 2015. (unfinished).

© 2025 Forms of Boredom Advertised as Poetry

Theme by Anders Noren — Up ↑

Recent Comments