I exist in two places,

Here and where you are.Margaret Atwood, Corpse Song

It was a Thursday. I am almost certain of that. I was thinking about wars. They are everywhere, they were on my television set today. I struggled to engage, to endure the blank truths of the living world, but apathy dripped like static down the screen. I tried to care all the same. I want you to know that I tried.

And I missed you–I want you to know that, too. I felt your absence like a stillborn limb. That day, the white rooms were as quiet as light on water, and I missed you. The astral core of an iris contracted, and I missed you. The birds recited some babel-tongue song, and I missed you. The ocean gnawed at a cliff’s edge, and I missed you. The fireworks bloomed and I missed you. My brother smiled and I missed you. It was raining and I missed you.

I have always loved the shadows in my mind. But you, all of you, recoil: you draw back from the very mention of them. How can you hate such vivid parts of me? They are not always trying to kill me off. They can be so wonderful–you would not understand. It is hypocrisy, I think. You see these things hurt me. You feel that they should not. You protest their harrowing presence, and so hold the harbingers of my insanity to a higher standard than your own compromised selves. Stop trying to decide what to make of this flesh, this me. You know, in your heart of hearts, that it is not possible. Look closely at what I am.

Just the other evening, after yet another trying session, my senses became confused. They bit like frost and boiled with their own incoherence. So I wrote. I wrote about everything. I wrote about bed sheets, and their velvet felt lilac. I wrote about a girl I knew, and heard a softness like rosewater. I wrote about the piano beneath your window, and felt the winter I spent with you in gradients of E minor. I wrote about sex and it tasted silver. But when I tried to write about myself, about everything that happened this spring, I could only hear the shape of my bruises. So I stopped. I had to stop. It hurt too much to go on.

How can I learn what I am, when what I am is all that I ever thought I knew? There is still so much left to understand. What makes me feel like this? Why do some people stay? I sure as hell never planned to.

I am immersed in the caustic Atlantic: its eerie green-blues curl in toxic, foam-tinged tongues of brine. My consciousness drifts between two broken nations, seeking solace in both, finding respite in neither. I am disparate; separated, as they are, by ringing chasms of salt water and wind. There is not even the faintest hope of a homecoming for me. But sometimes it is all right to be here, in this place, where I am restless, reverential, half-haunted with the memories of some strange other life.

Exhausted, always, by this mind that flips like a tarot card, I watch the tortured dusk of the past take form. I feel you emerge, a chameleon: lips curled, air-eating. Your stomach glows the burnt-gold of embers that fracture under your skin. I cannot recall my own father’s smile, and yet I remember, with perfect clarity, the way your hands moved when you rolled cigarettes on the streets outside of a bookstore café. Your joints unfolding like poetry, the lightness when you laughed, the invaluable instances of tenderness, our apologies, my convictions, your entropy and bright, bright eyes. I know how these things felt, but I am already forgetting your voice. What does it matter, anyways, if I loved you at the end? Contention, contentment, condemnation, contempt: now I just want to drive my teeth into your throat and taste the warm-as-salt miracle of your skin once more. And I want you to want me to.

All of that time I spent fear-filled, striving to achieve some fiction of normalcy: those were the moments that I could have spent loving you. I am sorry for not knowing that. I am sorry for knowing it now. I am sorry that you loved a virus. I am sorry that I let you. But sometimes I think that I should hold your mind to the fire: extract a confession, a catharsis, a promise, a penance, from the tongue that I once held like communion between my teeth. Are you blameless? How can you be? I was dying, did you fail to notice? Sometimes, when I am scared or sick or sleepless, I ask myself, wretchedly, if perhaps you preferred not to look. For if you had, you would have seen me, you would have seen how unhappy I was. Deep in the innermost core of me, I suspect that you were too clever for your oversight to have been a mere carelessness.

But how can I ask you to suffer this: how can I want you to know, for any reason at all, what it feels like when the doctors cut into me? I could not even bring myself to make you look. I never wanted you to see what was happening to me. And how can I hate you, for not engaging, not trying to save me, when I would only have consumed each earnest effort, and become some parasitic thing: leech-like, useless, hateful even to myself? But look at me, really look. It is safe to look now–for I am irreverent, and I am far away, and you could not help me if you tried.

It is my fault too, you know. After all, I let it grow inside of me. Childless mother, nightmare that I am, I should never have tended to it. I should never have made it love me. And I never would have, not ever, had I known that I was to love you. I still remember that morning: the sky was clouded, shrouded in white. White like the narcissi, white as blindness: the flames licked at my wrist until I was cleaner than snow. But why did I hate myself so? Maybe some part of me knew. I wish that I had murdered it then, this thing that now murders me.

You never ceased to confound me, with your lovely brown eyes and your arresting phrases and your aimless wants and your steadfast ways. But you loved what I wrote, what I am. I should have held fast to that.

So what does it matter, really? You are not as she was: she had a a way of making me want her, of wresting form and expression from my reluctant heart until, wary though it had become, I felt willfully and ecstatically, imbued with a passionate vulnerability that all but silenced my astounded soul. And when she seared and scalded me, I knew her too well to draw back. I understood quite clearly what I had to do. It was not my love she needed. It was my language. And that was fine. I have enough words left to give, I think. I can barely face each day upon waking, but I could write for a lover like that until the night waxed sanguine and the stars fell burning from the sky. I could do it for you, as well. Do you want me to? Have you ever? Have you always? It could be both or neither. How very sightless I have become.

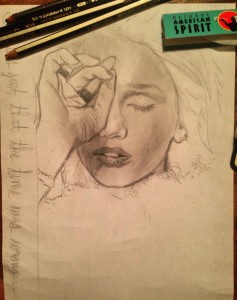

It matters not at all. This endeavor bears no purpose. This is a simple meditation on distance, on loneliness, on longing. Who is to blame for what I am? The soles of my feet are harder than cypress, and my soul is a diamond, corrupted by a spectatorial gaze. I enter the world like a lidless iris: a naked pupil, incorrigible and obscene. Drink, then, the pure blind blankness of my exposure. I am utterly lacking, I am as faceless as the moon. The eye, this eye, it is me: I am and am. So love what I forgot to be, this relentless, searching self.

Someday my mind will return to me–and I, my love, to you.

Recent Comments