Grief takes on many forms, including the absence of grief.

Alison Bechdel, Fun Home

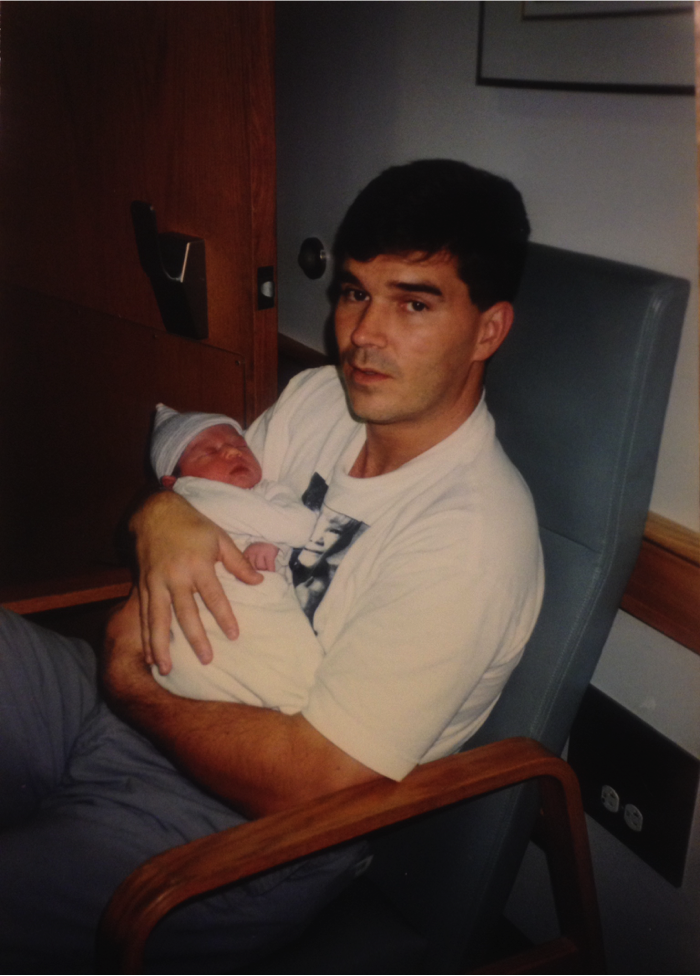

I was fifteen when my father left my family—and in my search for an artifact of memory, I came across a 1996 photograph of him holding me in the hospital room where I was born (Fig. 1). The second artifact, a photograph taken by a friend during my freshman year, shows me looking up from reading Dante’s Inferno in my high school dining hall (Fig. 2). The longer I compare the photographs of my father and I, the prouder and more sickened I am by how similar we look: the same small mouths turning down at the corners, the same wary brown eyes, the same thick, dark eyebrows, the same straight noses with an indent on the bridge, the same oddly precise curve to our chins. But most striking of all is the similarity of countenance as I glance up from my reading and he glances up from my face—the identical, slightly bemused expressions as the camera draws our attention away from something that we had been fascinated by.

In the first photograph, the 1996 one of my father and I in the hospital, he holds me to his chest more closely and tenderly than I can recall in any of my conscious memories. Perhaps it was as early as the hours following my birth, then, that the history of my love for my father became joined with the history of my body. Bechdel’s memory of her father bathing her—the “…suffusion of warmth as the hot water sluiced over me…the sudden unbearable cold of its absence” (Fun Home, 22)—is a memory of mine as well. I can recall, as clearly as if it were yesterday, the sensation of lying on my back as water filled each crevice in my body. When he read to me in bed after my bath, it was in these gaps and margins of my still-breathing flesh that I began to imagine droplets of ink and little pools of Times New Roman font; it must have been during one of these instances that I decided to become a writer. My father’s specter haunts each scar and bruise upon my body, although they were inflicted not by his hands, but by mine. I learned that the reason that I would never be called beautiful was because I looked too masculine, too much like him. And he was even there, in person, when I underwent the agonizing experience of tattooing the right side of my head. He was the only one I would allow to accompany me: at times it felt though we were both seeking some sort of clarity in the searing reverberations of a needle against my skull.

But the physical intimacy in the 1996 photograph is not only emergent in the way my father presses me to his chest. My mother once told me that my father had always wanted a little girl: maybe no one ever told him that little girls become women, or maybe he just never listened. At any rate, in the four-page, anguished letter that I sent in the weeks following his departure, I wrote, “You are missing the years of my life when I need you the most—the years when I start to become like you.” This sentiment has never seemed more evident than in the uncanny resemblance between the 1996 photograph of my father and the 2011 photograph of me—a visual transmutation that merges fifteen years, two dueling identities, and a single shared history in the identical expression on both of our faces. When I happened across these two artifacts of my memory, I stared at them for what felt like hours, searching for answers I felt sure they would never be able to give. More than anything, I wanted some kind of explanation for the interchangeable expressions of the man who made and unmade me, and of the daughter who loved and hated him as she could only have loved and hated herself.

To my own surprise, my artifacts of memory posed a tentative resolution to this question. The 2011 photograph, taken in Lower Right of Commons, is the image of someone whose father has already told her he hated her. She has already opened her skin with the edge of a razor, already sought solace in cigarettes, substances, and the bodies of others. The inherent sameness of my expression and my father’s is therefore paradoxically augmented and juxtaposed by the dramatically differing impacts of our shared history: this endless range of contextual differences between each photograph redefines what it means for us to be joined. I am indeed my father—not only what he is, but also that which he never was and could never be. The simultaneous equity and differentiation between the two photographs has compelled me to believe that the imposition of experience upon a subject by an object necessarily distinguishes one from the other—that the subject emerges not merely as the object’s double, but also as an autonomous result of the actions inflicted upon it. I therefore owe vast magnitudes of my selfhood to the influence of my father: but my selfhood is ultimately my own.

It has taken me an uncharacteristically long time to write this piece: perhaps because, while I have written about my body, my sexuality, my depression, my addiction, and myself, I have never truly stricken the untested heart of my own vulnerability. I have never before written about the childhood hatred and adoration that formed the burning core of who I am. The 1996 photograph of my father and I was the most difficult “text” I have ever had to analyze; ultimately, though, it has proven worthwhile. I have always wanted to know if there was any time before all of our symbiotic resentment, any period of life wherein my love for my father was not rendered injurious by the pain he inflicted upon my body and spirit. I wanted to know if we were ever happy, if his love for me had ever even vaguely mirrored my love for him. The tenderness of the 1996 image facilitates the construction of such a memory—one that predates the years of verbal and emotional dissonance. The photograph’s existence, and my discovery of it, creates the visual reality wherein our conflict is neither existent nor foreshadowed, and where I will always be one with my father. It provides me with a history that distances my love for him from the extent and impact of what I experienced.

I chose the photograph not only for its intimacy, its sense of physical merging, but also for the scarcity of detail and the sense of ambiguity. If I could have written something confident, definitive, or self-assured about that image, then the entire piece would have been a lie. When the photograph was taken in 1996, just as in every moment and memory we share between us, my father did not give me much to work with. But this time, he might have given me enough.

Leave a Reply