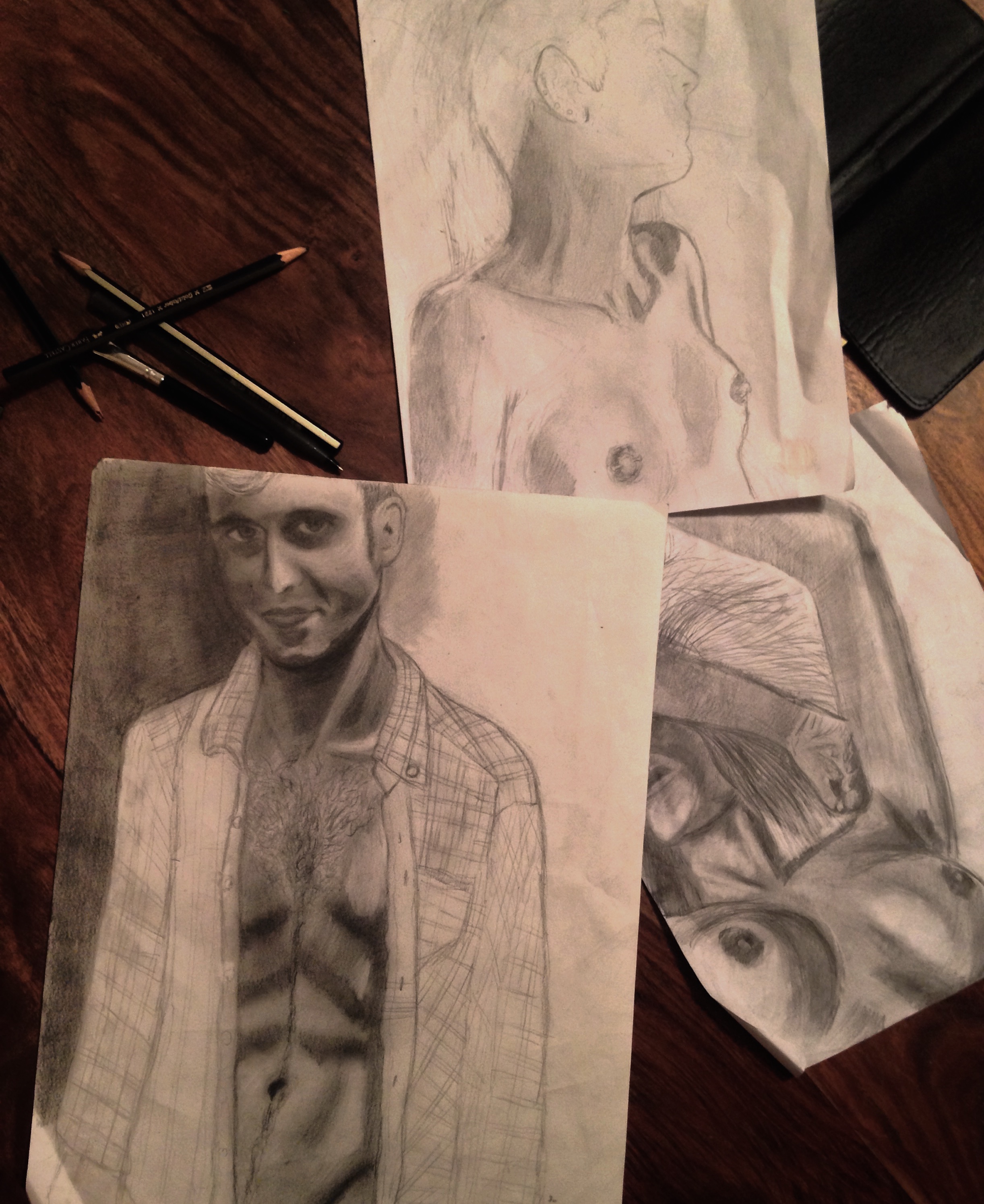

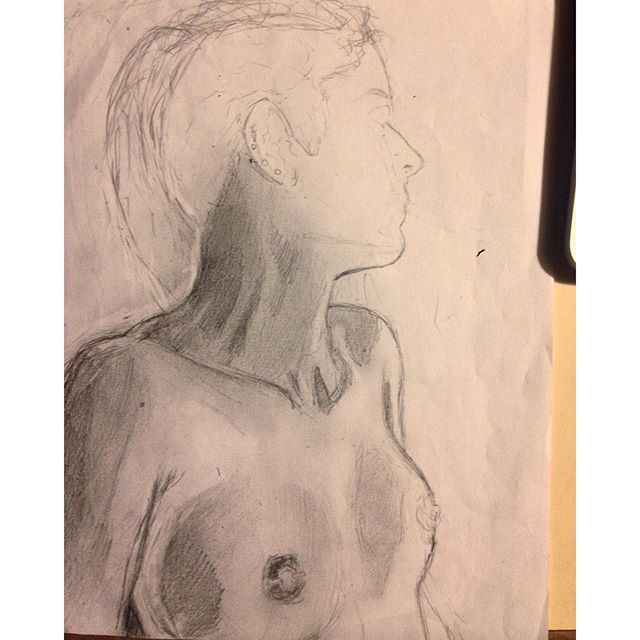

charcoal and #2 pencil. january 3, 2016. (unfinished).

just an update on a few of the pieces I have been working on

charcoal and #2 pencil. january 3, 2016. (unfinished).

just an update on a few of the pieces I have been working on

For my mother, who knows who she is.

Alison Bechdel, Are You My Mother?

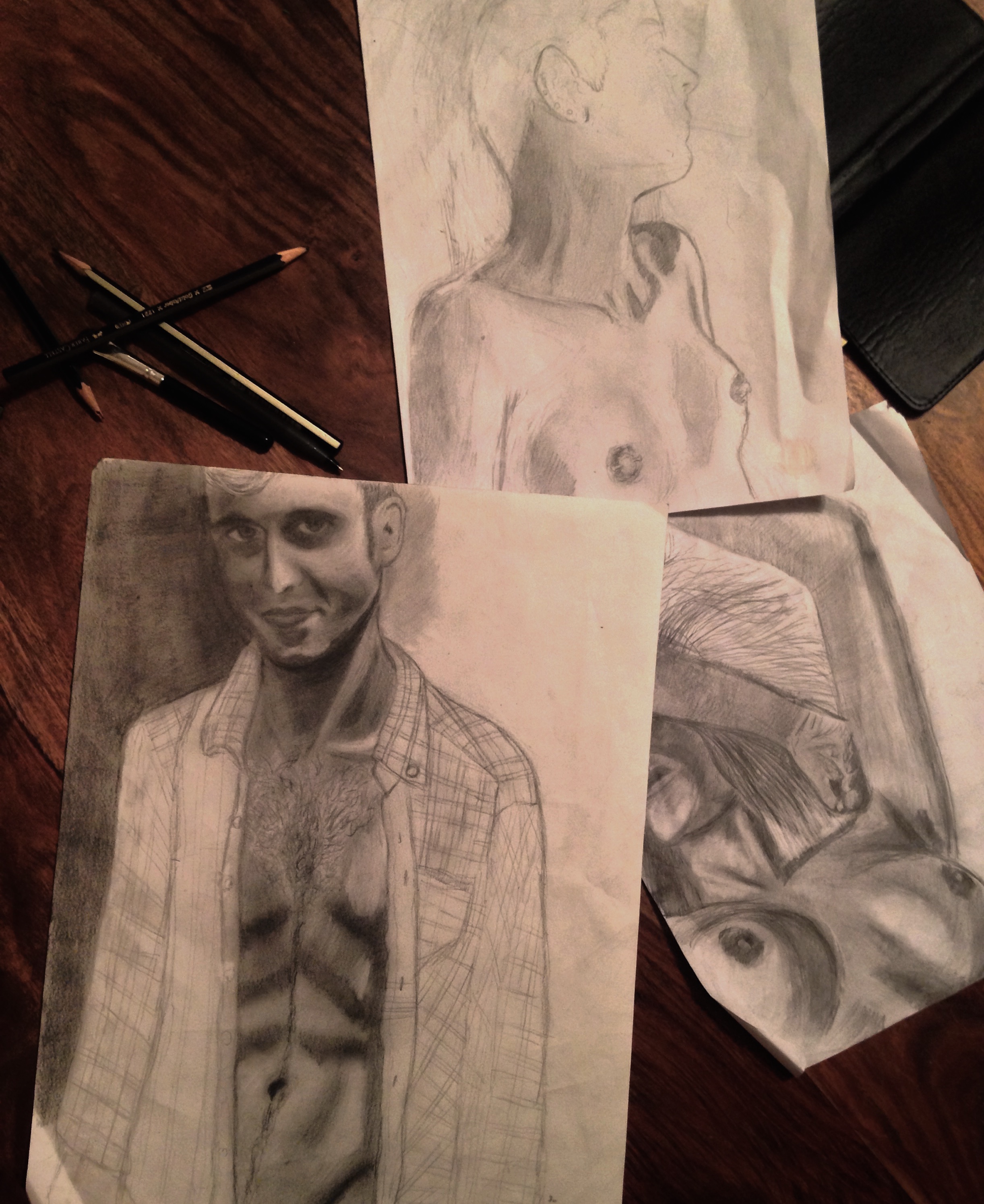

I recently had the pleasure of working with Corinne Singer and Maggie Kobelski on Corinne’s ongoing series in feminist self-portraiture. The first installment, entitled “Mother, May I?,” came into being in late December when, at the seaside town where I once spent my childhood summers, I walked into the Atlantic Ocean wearing my mother’s wedding gown.

For as long as I can remember, it has simply been expected that I would marry in that dress; but following the deterioration of my parents’ relationship, my struggles with mental illness, and my efforts to come to terms with my own sexual and gender identity, the oppressive implications of such an assumption took on violent significance. Always symbolic of conformity, by the time of the shoot my mother’s wedding dress had become a representative site upon which the traumas of my adolescence—the toxic constraints of heteronormativity, the lingering anxiety of disappointing my mother through my unconventional state of being—were made manifest.

In some ways, “Mother, May I?” functions as a visual counterpart to “Love and Other Theories of Subjugation,” wherein I describe an allegorical scene of submission in (and to) the waters of the Atlantic, reflecting upon my own psychological need for respite. In other ways, it was a challenge to my own body: kneeling in ivory satin among frigid water was a means through which I could explore my own physical limitations, and in doing so, engage in an incomplete (but perhaps not entirely futile) effort towards transcendence. In the latter regard, the entire endeavor can potentially be read as a reflexive, even masochistic act; more than anything, though, it was the visual extension of my understanding of the human body as an intimate site of desire and revolution.

The conceptualization of this piece drew heavily upon the feminist tenants of physical reclamation. My status as a neurodivergent, differently abled queer person with a complex identity that includes ‘woman’ is visually and thematically evoked in the lines of Sapphic poetry painted onto my body: the characters along my collarbone read, “Someone, I say, will remember us, in another time,” while “Hymn to Aphrodite” extends across my back and shoulders.

Efforts at self-portraiture are complicated by the many facets of my identity that cannot be reconciled. With regards to the trajectory of the photographic narrative, however, the themes that come immediately to mind are captivity and sacrifice, abandonment and solitude, violence and desire, sensuality and subjugation, shame and self-medication, resistance and liberation, baptism and rebirth. In my artwork and my writing, I have rarely achieved the sense of catharsis that I experienced when modeling for this piece.

This narrative is dedicated to my parents, my queerness, my body, my resistance. It is dedicated, in short, to the willful destruction of beautiful things.

1. Surrounded by containers of makeup, clad from the waist down in my mother’s white dress, I face a mirror imbued with my form. Although it was originally intended as a test shot, I begin to view this photograph, the first in the series, with uncertainty, and then fascination. It is transfixing to gaze upon my own image, twice framed: so strange to see myself unintentionally misrepresented as a lovely and feminine thing. Sunlight filters through the windowpanes, soft against bare skin: gradients of shadow, beautiful and subtle, adorn the folds of fabric. In this effort towards self-portraiture, I am the object of my own contemplation: the project begins, as it likely should, with the ongoing question of my gender, and a conscious performance of the self.

2. Kneeling in the sand for our carefully constructed evocations of traditional wedding photographs, the first thing I am conscious of is being colder than I could have imagined. The diaphanous fabric of the veil is cast away from my face, revealing an incongruous joining of propriety and discomposure. The dress, which encompassed my mother’s form so gracefully when she was only 25, is too large for me: reams of white satin drape awkwardly over an angular frame emaciated from cigarettes, sleepless nights, and too many other mediums of self-consumption. Tendrils of dark hair are not quite enough to cover the shaved and tattooed side of my head. My eyes are shadowed, deep-set; my skin is scarred and pale; my lips are ashen, almost anemic; my countenance echoes the muted tones of the landscape surrounding me.

3. These are the photographs that my mother dreamed of someday seeing when she gave birth to me, her only daughter. But like the dress itself, they do not fit: they are unsettling, dissonant. Discontent textures each image: the specter of a captivity that has haunted me since childhood, informing my longings and impeding all efforts towards resistance. I emanate a stark sense of discomfort with the parameters of my sociocultural existence; is this is the only permissible way for my body to fill the space around it, as the object of another’s gaze?

4. I cannot be adequately represented, or even contained, by those sterile, bloodless images of a woman that I am not. So as the daylight begins to fade, we focus increasingly upon the boundaries associated with gendered and sexual conventions, and the instability of desire that such margins ascribe. The tide advances: I move towards it. The veil is disposed of; the shaved hair, the many piercings, and the dark ink become visible along my skin. No further effort is made to keep the dress from slipping off of my tensed shoulders as I crouch like an animal, anointing my face with water and marring it with sand. Makeup runs in dark rivulets, and my hands clench and claw at the earth, craving a nameless liberty. I am abject and full of rage. Rage for my mother’s abandonment, rage for my own psychological mutilation, rage for those years of self-loathing that gnawed away at my sanity until they made me what I am. My entire body reacts against the fact that I was given so little say in what I would be expected to suffer and survive as a woman, as queer, as fatherless, as alive.

5. These recollections inspire a natural, almost involuntary defiance: inspired by Yoko Ono’s “Cut Piece” and its connotations of sociosexuaul violence, we tear away at the fabric of the dress, mangling gossamer sleeves, exposing bare skin, smearing wet sand across the intricate lace bodice. These willful acts of destruction constitute, for me, a rejection of the imposed existence that I accepted for too long; but no act of violence towards my half-remembered history can alleviate the isolation of the present. A vast expanse of water, smoother than glass, serves as yet another mirror in which to survey my own solitude: nowhere is it clearer how damningly alone I am, even as the subject of my own narrative.

6. My reflexive response to the most isolating moment of the shoot is the immediate assumption of a more sensual pose: within misremembered paradigms of sexuality and subjugation, I seek solace from “my grief and maddening solitude.” The impulsive motion is simultaneously masochistic and liberating—what better respite from the brutal senselessness of this existence, than a reckless and ongoing engagement with the selfsame acts of desire and decision that every known standard of gendered propriety has attempted to exert from my still-breathing form? Skin exposed, body rigid with the cold, I kneel in the shallow waters, gripping my heels with my hands…

7. … and then wrap my arms about myself defensively. Desire followed by vulnerability, longings complicated by half-realized fears, there is something almost fragile in how thin I appear, enshrouded in the dissembled silk that floods around me in tides of white.

8. Something close to beauty, utterly strange and distinctly sorrowful, emerges from these positions of imprecise susceptibility. Kneeling upright among the currents, I evoke, almost unconsciously, a sort of seraphic imagery: “aurochs and angels, the secret of durable pigments…the refuge of art,” in the words that Nabokov wrote, which imbued me with melancholy so many times over, leaving their impressions in the contours of my memory and soul. My posturing is both natural and dimly mythological: recalling violence and self-preservation.

9. Fingers numbed, it is nearly impossible to light a cigarette—but I know that if anyone can do it, I can. The act itself illuminates my bizarre, precarious relationship to smoking and social shame: the stigmatized practice of self-medication that has come to inform, and even characterize, my identity in so many relevant ways.

10. In my dissonant conflicts with “this slowly dying body,” smoking is a habit I engage in because it allows me to remain as sane as I am capable of feeling; it is an addiction born of trauma, which has nevertheless become entirely my own. I can claim each breath I draw, and feel no shame for the choices I have made, even as they consume me. There is, after all, a certain absurdity to the thought of a world that has nearly killed me in so many different ways, chastising me for something so inconsequential. For me, for now, smoking is an act of strength and resistance: it is a reaction to the culture that reprimands self-medication without paying mind to its origins or the consequences of its absence. After all of the ways in which I have been damaged or undone, this, at last, is an action I can inflict upon myself.

11. By the time the cigarette has consumed itself, burning away into ash, I evoke a very different image from the subdued girl with the fading roses and downcast eyes. Intrepid and irreverent, my resistance has carved a space for my androgyny, my sexuality, my multifold and semi-performative identity. The dress has been destroyed beyond repair, leaving no means of going back, of mending whatever damage has been done to that beautiful white fabric. I have torn it from my own body, and am occupying my surroundings now as more than an object of desire or aestheticism. I am too cold to feel my own skin, but the rhythm of my pulse is more realized than ever. My eyes are burning, framed in black; my hair is disheveled; the protective lines of Sapphic language have washed away, leaving only my bare skin and its many strange desires. There is a primitive, almost feral element to my defiance.

12. Despite all of my frustration and retroactive grief, it is a mournful and lovely thing, to lay waste to the dress my mother thought to see me married in. The gown is still beautiful, even in its ruined state, as I kneel beneath the luster of these radiant skies. It feels like a baptism, to immerse wholly in the currents, to reckon unflinchingly with the girl I was, the person I am, whatever I have yet to become. In some wonderful sense, it is the inimitable extension of that longing I have expressed so many times before, to leave “my life and my name and my consciousness in the keeping of those waters… to know that there is someplace left to lose myself.” Is this what it feels like to finally begin to heal?

13. Maybe—but then again, maybe not. After all, despite whatever language and meaning I impose upon it, the story the fabric tells is simple. I need a new beginning. I think I always will. So on the shorelines of my childhood, and in the object of my eternal fascination, the sea, I try for the next best thing.

14. Amid those timeless waters, I evoke the sensation of being reborn.

We have to consciously study how to be tender with each other until it becomes a habit.

Audre Lorde, Sister Outsider

Every time I bleed myself out in front of a blank page or a computer screen, I am reminded that it is damn near impossible to communicate fully, to forge the connections and the intimacy that I crave, when writing so directly and consistently about myself. But I continue to do so, for now at least, because for all of my confusion and my restlessness, I am something that I know. There are worse things to write about than that, I suppose.

Ghosts of my past reemerge with the dawning year. There are bones that I never put to rest, and people I could not keep alive; yes, that beautiful girl died, with white roses in her hair and eyes, but it was not entirely a tragedy. People change, after all, and what of it? If you do not know what I am writing about now, it is because you were never intended to understand. But for the briefest instant in our burning worlds, she was mine, and I was hers. That will always be true, it could never be anything else. What more can I really care to know?

How long do resolutions last? I am impractical, but not entirely naïve. I understand that a turned page in a marked calendar bears no real significance. I have never had the constancy or the resolve to keep the commitments I devise; but I will make my promises, all the same.

In 2016, I will remember, always, the treachery of pleasure: the unspoken wariness of anyone whose love, for as long as they can remember, has been mingled with trauma and directionless sorrow. I will remember that I am a body in need of protection, and that this is a beautiful thing. I will remember to stop projecting my fierce and nameless needs onto sites of imposition, be they desirous figures or gentle minds. I will remember to find secret, tender parts of myself and keep them very safe: to give less love where it is not wanted, and so carve out a space for myself in the world.

In 2016, I will find more spheres of women, queers, and people with complex identities that may include “woman.” These communities love deeply. I want and need to be cared for in that way. I will touch and be touched, I will write and remember; I engage in these acts already, but I will try to spend less time fretting over inevitable endings. Perhaps this is the first step towards finding a kind of love that does not devour me, towards knowing the value of my life and mind.

In 2016, I will live fiercely. Where I walk, I will strive to be remembered. With passion and precision, I will fall in love with what I am. I want to be adored: I want to suffer and survive until no one doubts that my resistance is also liberation, and that I am the the better for it. When I lose myself within a labyrinth of my own conflicted desires, as I always eventually do, I will be more and less than Icarus, still alive, still in flight, and burning, burning, burning; they will call my name on raucous evenings, and remember me on city streets when the night is gone.

As I write this, I am filled with a quiet joy. The ocean breathes, thirty feet below me. The stars blaze softly. This, right now, is one of those moments when I am really present. There are no barriers, no secrets, no lies left to tell. I am not distant. I am not guarded. I am whole. It does not matter if I keep these resolutions, because I have written them, and so have willed them into some sort of existence.

Maybe if I reckon with my pain instead of avoiding it, I will have nothing left to be afraid of. I know that I cannot have everything, but if I can create so much, and feel so deeply— even if I cannot necessarily survive it—then maybe I can start to make some sense of this inane world.

I will move slowly and determinedly towards a more harmonious state of being. The entire endeavor is cyclical, of course; I will inevitably become bored again, live within those psychological extremes that most people will never know, and when my mind and body have sufficiently consumed one another, I will ease myself out of insanity and adjust once more to the rational world. Maybe some part of me simply does not want to be sane; maybe that is why I am so incredibly inept when it comes to healing. But the present task is simple, an effort towards stability. I want to believe that I am capable of that.

I will try to remind myself that, in instances of loss, I am not always entirely at fault. My world changes, I grow older: the person remains, but the feeling they inspired fades to memory, and then to nothing at all. So I will refrain from crucifying myself, over and over again, on the transience and the tragedy of those pleading words—I need you to just hold on, until I am sane enough to love you again.

Am I really so alone? The only one grieving gently, the only one who retreats from the indifferent cold of an empty bed on sleepless nights? The only one who tires, at times, of being so deeply alive? Surely, somewhere, there is someone just as conflicted and impassioned and flawed as I am. Could we teach one another to feel more completely? Could we heal whatever mutual wounds our histories have inflicted? Could they make me feel safe again? Could they tell me who I am?

I will always be strange and I will always be displaced, because so much of my existence is determined by the perception and conclusions of a thousand other minds—such is the tragedy of the social world. But that is not so terrible: I can withstand the voyeuristic impulses of the culture I engage with, I can survive the stigmatization that I learned, in my early adolescence, to simply expect. And I can do so alone, if I have to.

Let me remember this moment. I love to know that I can feel this way. It is so rare and so strange, that I should exist and be heard. I am not sure who or what I am writing for now: lovers or strangers, confidants or companions, the woman I eulogized or the self I have yet to fully understand. But I will not apologize for this most recent engagement with the language of my own mind, however discursive or self-indulgent it may seem. I will not waste another year killing myself off for the respect of an audience that hardly exists. I will be different, and I will be better, for as long as I have the strength. I will write, and feel, and love, and burn, until there is nothing left to save.

Oh, my love, take me there.

Let me dwell where you are.

I am already nothing.

I am already burning.Sophocles, Electra

Mild December mornings find me listless and on edge, smoking cigarettes and drinking weak coffee in New York’s East Village. Listening to shit jukebox pop songs, avoiding street cabs and strangers’ eyes, I adjust to the insincerity of the city, immersed all the while in the dim paranoia that colors the wary reintegration of an insomniac into the waking world.

There are always days or weeks or months, impermanent instances wherein I begin to wonder whether or not I have lost my mind. Every time, I worry that I will not recover, that maybe this time, it is for real. And there is a certain joy in the reckless interest with which I navigate these temporary bouts of instability—cynical and strangely high-spirited, quick to laugh and slow to focus, I live like an exposed nerve: vulnerable, feeling everything.

I am always between worlds, haunted by that selfsame specter of displacement that strays through each new city at my side. I long for home, return to realize that it was never truly there to begin with, that it left with my sanity and my father on a cold grey morning so many years ago. It seems like a lifetime now. I spend holidays reliving each whiskey-dimmed wandering down the silent streets of England, dreaming of that directionless respite where my second life lies.

Just the other day, I decided that I had witnessed enough, and drove two hours north down a narrow highway until I reached an empty town at the edge of the Atlantic. There, a friend and I watched beneath saturnine skies as the ocean heaved against wind-chilled shorelines. We spoke in misremembered lines of poetry, for we had no language of our own with which we might express the enigmatic beauty of those waters on a moonless night. Our recitations perforated the silence, each word rewriting the margins of measurable time, and we returned home again in a haze of joyful abandon: smoking cigarettes, driving too fast, shouting the lyrics to old rock songs as they rang from a broken-down radio. Sometimes you have nights like those, and you understand that it is not so very terrible to live, to think, to feel. You remember that you have the constancy and love to form relationships that endure. You find solace within, and in spite of, a world that offers none. You live on, and on, and on.

I realize now that I may well be within the sensual bloom of my own existence. Am I entering it? Is it waning? I attribute my sexuality, my singular and self-contradictory identity, in large part to the fact that I am practically crawling out of my skin with fascination for the bodies of others. I do not accept the politics of compulsory heterosexuality. I am too passionate, too sensuous, too curious, too undone: I refuse to limit my experiences to any one gender. I want to be young and half-mad with desire forever. Live fast, die pretty—right? But I do not want to die at all. Not anymore, at least.

But there are times, I must admit, when I feel exhausted. Is it possible to reckon wholly with the impulsive passion of our own histories, without inevitably feeling older than we are? It would not be so tiresome, if I could only see these dimming years as inconsequential: if I could allow past lives, and loves, and losses to fade away into obscurity. But I have never known how to lie to myself.

Sometimes it simply does not work. Sorrows that are the most insurmountable, the most exquisitely damning, are always conflicts of positionality. Sometimes someone gives you everything they have to offer, and it still is not enough. The timing is wrong, your body is wrong, you need something that no one could ever give to you, and it makes you so happy and so sad at the same time: because you know you are as content as you ever can be, and you realize that maybe you will always feel this way, and you wonder why life at its best is so sweet but so sorrowful. It might sound pretentious, or even maudlin, but there it is. Perhaps in moments of melancholic stasis, we catch glimpses of who we are.

So how can you explain to those that love you, that remembering them is more difficult than catching smoke between your fingers? Nothing is sacred, not anymore. Every time I start again, another person, another place, it always ends with the same banal sentiments: I want you to know that I really did love you. That I really did try. Self-preservation becomes its own peculiar form of cannibalization: I lend my mind to intrigued strangers, and forget them all just as easily. How on earth could I have allowed myself to become this way?

In those rare moments when I am fully present, I find a peculiar comfort in feeling deeply: in eclipsing all that the other has to give. How many times have I lived over that stripped down bedroom scene, enthralled by the very futility of our efforts? Two uncertain strangers, wide-eyed, afraid of our own bodies’ desires, sharing nothing except a sense of fascination: intrigued by one another, by ourselves. Satiating nameless needs, engaging roughly in acts of tenderness: I will always remember the sweet and violent words you spoke, in the blush of that fast-approaching morning, when I found myself at your feet. You asked me to stay, pushing tendrils of hair out of my eyes: and what a choice I made that night—you still do not know the courage and carelessness it took.

In the weeks that followed, I dreamed vividly of a strange and hallowed place. There were garlands of asphodel in juniper branches, and mirrors imbued with prismatic light. You were there with me: you were nowhere else. When you spoke, you did so in gentle words tinged inexplicably with remorse. I understood you then, as I never have before or since; your clandestine yearnings, your hushed apologies as you took my fingers in your mouth. I felt the rhythm of your throat, those softly moving muscles that make your voice so low and sweet, and the strangest longing blurred my vision as from above you I glanced down. I wanted to inhale your waking consciousness in my memory and flesh, as your abandon breathed dimly through the twilight of my stirring form, submitting to my impulses, subverting what we understand to be the natural language of our desires. A silent pleasure nearly deafened me when your mouth moved in mine; I could know greater joy than the murmur of your heart beneath my hands.

How lucky I am to have found, in this absurd existence, such wonderful ways of passing the unwanted time.

Do not misunderstand me: I no longer have the patience for imprecise, diluted love. That is the best you could offer, I think, and so this feeing of mine is merely fascination, infused though it may be with tenderness and a certain sorrowful pleasure. Do I know you? No, of course not: I never really desired to. But there are facets of being that evade your waking consciousness. I learn to understand what requires distance to be known.

An absence bleeds within and throughout you, coloring your countenance like memory running through a living mind. Once, and never since, you gave that absence form through the parameters of your susceptibility and the language of your grief, reminding me of one who, in another time and place, did the very same. Hers was the body from which I learned my love and limitations; is it so surprising, then, that I should react as I did? My mind met yours in a flurry of misrecognition: that was the moment when I decided not to care about practicality or consequence, decided to survive whatever comes of this. That was the night I let you in.

I will not love you, but I like to know that I can; and that I would heal you, if I could. I give this potentiality less threatening form through a sort of detached curiosity: could I bring a person such ecstasy, evoke such adoration, that they never wanted to leave? It may seem callous, but I have been left all my life. I seek respite in these urges, but they manifest, at times, in fixation, and I simply cannot allow that. I have too much to think of, too many things to create.

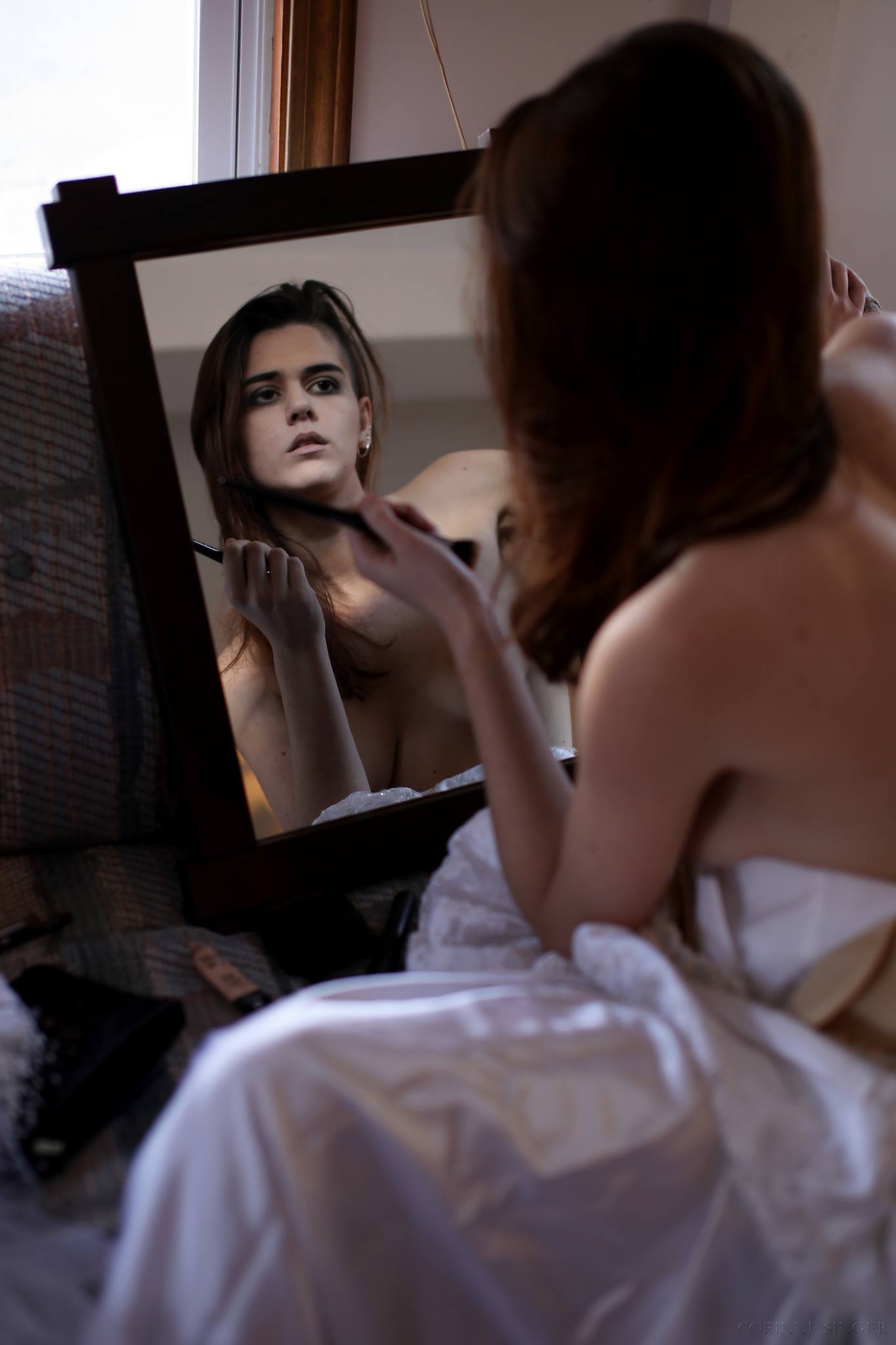

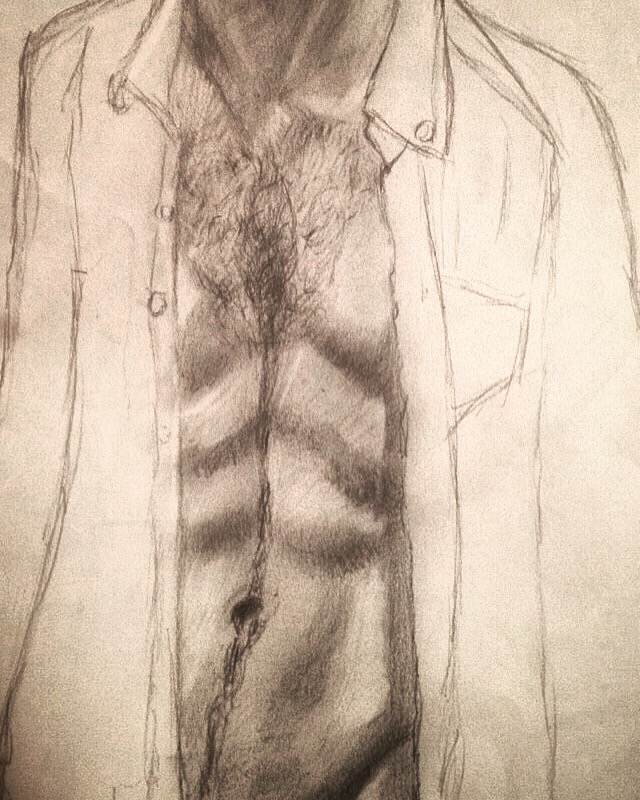

So I turned once more, in your case, to the confines of my mind: I framed you within my gaze, false remembrance serving as my means of forgetting, and regarded the visual construction of your form as I might an exorcism. You bled from my hands onto the blank page, leaving stains of charcoal along my fingertips, my wrists, the skin on my forehead where I pushed the hair back into place. Everything I touched, I marred as though with ash.

I chose the wrong person again, I am afraid. I always do. But then, don’t we all? And what does it matter anyways, when a thousand forms and figures pass through my periphery? Even now, another soon-to-be memory strolls through Oxford shops and alleyways, evoking all of the opportunities I never took. In the morning, her name is everywhere: it floods my mind in a thousand strains of music, running like rain through the cobblestone streets.

So where do we go now, what do we do? This cannot last, so want me now, and I will do the rest. Abandon your inhibitions, silence your lingering doubts: I have never cared much for complexities of circumstance, and I am never hard to find. I will remember the good days, and forget whatever else I can. When I write too often, it all starts to feel the same. I knew you, my darling, I knew you, I loved you, and I will remember you. I will, I will, I will—will I? Will you? What a strange and terrible thought it is, that I may wake tomorrow feeling nothing at all.

But fuck that, fuck all of it—I have too much left to write about. I am alive now, and two years ago that is more than I ever could have hoped for. I write for myself now, because in this senseless reality, I am my own best subject. I refuse to be remorseful, to water down my own existence to some self-effacing apology. Why be selfless where you can be satisfied? Everyone is surviving something, after all, and I am not even sure what it really is that I write about now. My hands shake with a thousand unnamed longings, but I am not suffering, not anymore. I do not want to die: I burn and burn and burn. This is what I am now, this is where I stand. It is precarious, it is absurd—but I love it, all the same.

charcoal and #2 pencil. december 15, 2015. (unfinished).

I would like to tell her, Love

is enough, I would like to say,

Find shelter in another skin.Margaret Atwood, Selected Poems II: 1976-1986

You take my head in your steady palm, push me gently below the surface; oceanic waves envelop me. Of course I cannot breathe, but I submit so willingly, drown so blissfully, surrounded by the rhythms of the sea. Memory and motion, a slow-moving cadence, my mouth seeks solace in that clandestine hollow where your hips meet the inner curve of your thighs. All around me, perfect stillness: I can hear your sighs above the water.

I am a living thing. I have lungs, a pulse, please understand: I cannot always remain beneath the surface for so long. I could only ever lay waste to what I am, kneeling breathless at the bottom of the sea; and yet, to hear those sighing, shifting waves I might have stayed a lifetime longer. I might have submitted to the ebb and flow of desires that were not my own. I might have surrendered entirely the dignity of my being, left my life and my name and my consciousness in the keeping of those waters.

Know now, and always, that this would have been done not for your pleasure, but for my own deliverance. It was wonderful, just once, not to exercise ownership over my private self. To be simultaneously desirous and subdued. When I surrendered to that current, to those tides, I was released, if only for an instant, from all of my grief and maddening solitude, from the discordant history of this slowly dying body. I only existed where the waters touched me. I was simply the surface of my skin.

I frighten myself sometimes. For all of my violent impulses and narcissistic desires, I am still so very gentle: a raw and open wound. I do not think that I am suffering, but perhaps I have been this way for too long to be sure. When I awoke, there were bruises on my knees, and I knew that my own fingernails left those imprints on my heels. This was subjugation, reduction to a purpose, the nature of which did not satiate that nameless need for convalescence that I practice and retain. Even so, I welcomed it. I had nothing to fear because my self was mine to give. Because all the while, I could feel an ocean breathing beneath my skin; and have you ever known an ocean to be tamed?

I wish that it were not so easy to fall into such tired clichés. They do not lend form, or truth, or meaning to these hollow words. But still I must wonder if I am being drowned, or saved, or baptized. I must always long to have been taught whatever difference lies between love and degradation, must always wish that they need not be forever joined in my myopic eyes.

I want to know now what sweet and gentle things my soul is capable of, how many ways I can work myself inside of you, but with intentions, for once, wholly pure. I want to know how many ways I can bring ecstasy to another living being. This desire is more than physical. It is cerebral, rooted in the mind that has tormented and sustained me, in the desires and the decisions upon which I will likely die impaled. I have to know myself, whatever the cost. This is the choice that I made.

So if you ask me to stay, I will try to, for as long as I can feel this way, and as long as these melancholic pleasures still murmur across the shorelines of my skin. I will remain and remember the best of these uncertain days, awaiting the inevitable realization that your deficiencies are neither transcendent nor justified, that I can no longer misrecognize myself within the depths of your eyes. And when I find that I cannot go on, that this lie of ours has lost both its form and its meaning, then I will leave without pretending to understand why. I will return to my words and to my solitude, and my heart will forever know a quiet tenderness for those hands that brought me such joy as they ran, like light over water, along the length of my bared soul.

Soon I will remember that I am more than roses. That there is a world and a history written into the folds of my skin. That there is a language to my movements and desires, incoherent though they may have been rendered by the immutable absence of one capable of translation. This is the day you will lose me.

Broken, torn, tasted, I grow weary now of searching hands, of stripped and selfish love. I want to be unfolded, opened, turned back upon myself in reflexive ecstasy like the pages of the books I have loved so well since childhood. But I am afraid that I am no longer the same body that I once was; what knelt there among the restless waters, this fragile expanse of skin over bones, the abject eyes, the notches of my spine—that was not who I am, but what was done to me. My form has become prismatic, all vertebral ridges and geometric planes, wasting away towards nothingness (as are you, my dear), evoking its own masochistic history.

I want to know that there is someplace left to lose myself. I want to submit to these waters, toxic and timeless, and taste the salt and sacrifice of my willful subjugation. I want to feel your hands along the margins of my body, reminding me gently and irrevocably of how very alive I am.

I am tired. I am so, so tired. It is never anyone’s fault when I begin to feel this way. This is the longing that lies at the heart of my ecstasy as well as my grief, texturing my writing, my loving, and all of the directionless longing in this self-consuming mind. I need something that no one could ever give to me; there is not a body in the world that can shelter me now, not even my own.

Perhaps it would not be so terrible, then, to give myself up entirely; to limit this mercurial existence to whatever pleasures my body can provide. Is it really so different, after all, from the decision I made two years ago, in becoming an organ donor?

So someday, please, if the time has come and you still remember this, make sure they take whatever they can from me; whatever is useful, whatever brings peace. The lungs will be worthless, but there may be something left for this body to give. As for the rest, bury it at sea. Do not hesitate, do not delay. I will be ready then, I promise you, to look upon the Atlantic once more.

Jane Eyre and Villette are notable for their respective narrative engagements with the notions of faith and female desire. Even as these novels establish a common thematic ground in Christianity, elements of the supernatural, and even of paganism, infuse both texts. The complex spiritual, political, and erotic inclinations of the female protagonists in these novels are simultaneously echoed and explored through a variety of supernatural gothic tropes; using images of phantoms, madwomen, and mysticism, both texts allow for a larger discourse surrounding the complex relationship between gender, spirituality, and the body. In both cases, mystic narrative elements underscore both the political ideals and the cultures of legend in which much of Brontë’s work is grounded; ultimately, through the supernatural elements of Jane Eyre and Villette, the Victorian Gothic enters into a conflict with Christianity that echoes the proto-feminist themes of each text.

The supernatural facets of Jane Eyre are manifested in large part by the vibrant imagination of Jane. Immediately preceding her first encounter with Rochester, Jane recalls, “In those days I was young, and all sorts of fancies bright and dark tenanted my mind…and when they recurred, maturing youth added to them a vigour and vividness beyond what childhood could give” (Brontë, JE, 132). It is not irrelevant that both in this passage and in relation to the novel as a whole, Jane’s creative energies and spiritual inclinations are emphasized and discussed in relation to the supernatural. Brontë’s attention to Jane’s vivid, complex imagination, which lends the text a distinctly feminist ethos through its uncommonly multi-dimensional representation of the psychology of a Victorian woman, draws heavily upon Jane’s fascination with the mystic elements of her world. Rochester also frames Jane as a preternatural being throughout the novel, describing her as “elfin” and “fairylike,” and drawing her self-image into conflict with the devout Christian identity that she attempts to forge over the course of the novel. The concept of motherhood within Jane Eyre occupies a similarly mystical positionality within the text, most notably through the recurring narrative presence of the moon, which recalls pagan lunar rites and a symbolic relationship with the spiritual forces of maternal power. This is particularly evident in the character of Diana, whose affectionate nature and blood relation to Jane allow her to act as a surrogate mother figure, and whose name recalls the Roman goddess of the moon—a deeply autonomous female figure who recognized no patriarch and is still worshipped within many contemporary pagan spheres. In addition to functioning as a signifier for female mysticism, however, the moon in Jane Eyre is also a deeply sensual image, and often functions as the backdrop against which Jane negotiates her romantic and erotic interactions with Rochester. In this manner, the moon embodies a relationship between paganism and female sexuality that corresponds in turn with the final and most obvious instance of the fantastic within Jane Eyre: the “madwoman in the attic.” Like the image of the moon, Bertha Rochester represents, among many other things, Jane’s repressed sexual desires. Functioning simultaneously as Jane’s double and as the deepest source of her anxieties, this supernatural trope of the insane woman (and foreigner) in Jane Eyre creates a frightening gothic embodiment of female erotic desire, bringing elements of Jane’s own identity into direct conflict with the Christological, patriarchal values of the society she lives in.

In her essay “Gothic Desire in Charlotte Brontë’s Villette,” Toni Wein proposes that, “Even more than Jane Eyre, with its madwoman in the attic, Villette is a haunted text. Bronte possesses her literary heritage by creating a surrogate Gothic” (Wein, 735). In Villette, the supernatural once again forms a conflict-ridden intersection between sexuality and the Christian female body. In Chapter XII, Lucy describes a legend that states: “that this was the portal of a vault, imprisoning deep beneath that ground, on whose surface grass grew and flowers bloomed, the bones of a girl whom a monkish conclave of the drear middle ages had here buried alive for some sin against her vow” (Brontë, V, 117-18). Like Bertha Rochester, the ghostly nun in Villette signifies the repressed sexuality of the narrator: descriptions of growing grass and blooming flowers evoke an image of fertility and sensual feminine life, while simultaneously representing a sinful female body that has been quite literally subdued beneath the earth. Even the “true” identity of the nun has connotations of sexual impropriety: Ginevra and her lover rely on this disguise to conceal their misconducts. Furthermore, the very notion of a spectral holy woman induces a specific and powerful visual joining of Christianity and the supernatural, and even though the “phantom” is revealed to be only a disguise, its image continues to haunt the text as a whole. Lucy is similar to Jane in that, despite living in a patriarchal Christian society, she operates within a complex, imaginative world wherein her erotic desires become inextricably bound to mysticism and the supernatural. With regards to Lucy’s eventual unmasking of the “ghost,” E.D.H. Johnson observes that, “Lucy is treading on more than the flimsy props of a silly hoax; she is rending the whole fabric of make-believe that has swathed her private world of fantasy” (Johnson, 335).

Of course, both Lucy Snowe and Jane Eyre are Christian characters, and are in fact quite devout in their faiths. In spite of her social othering in a predominantly Catholic community, Lucy remains staunch in her Protestant beliefs, while Jane constantly seeks the protection and guidance of God throughout her journey. Even so, the status of either woman as a moral paradigm of Christian femininity is greatly compromised by each one’s relationship to the supernatural elements of her respective world. Jane Eyre and Villette each reveal subversive and controversial truths about their female protagonists, and specifically their bodily impulses and longings for equality, through the mystic elements of the narratives and the manner in which supernatural figures function as thematic doubles. Professor Robert E. Davis explains, “Gothic traditions go on renewing themselves at the uncanny sites where culture simultaneously encounters its profoundest validation and confronts its most destabilizing uncertainties” (Davis, paragraph 5). It hardly seems coincidental then, that the presence of the supernatural in both novels echoes the feminist discourse that Brontë initiates. Occultism and paganism, with their relationship to “goddess religions” and the supernatural, occupy a unique point of destabilization within Victorian literature—they exist in theological tradition as some of the only pre- or anti-patriarchal mythologies with roots in Western culture. Although both Lucy and Jane are Christian women, the radical nature of their social and erotic desires binds them to these mystic, sensual, and anti-patriarchal elements of the occult.

Davies later goes on to explain the gothic tradition’s relation to the cultural parameters surrounding human understandings of the body, morality, power, desire and secrecy, writing: “…[the Gothic] furnishes a culture largely severed from traditional religious iconography with metaphors for the exploration of the terrors of selfhood, mortality, and the limitations of the human, using and distorting what is perceived to be contemporary culture’s only remaining source of possible transcendence: erotic love” (Davis, paragraph 5). It is therefore unsurprising that the complex and at times irreconcilable fissure between Christianity and supernaturalism within both Jane Eyre and Villette shares a common fixation upon the sensual impulses of the female body. Through their usage of the preternatural, both texts engage in feminist discourse by treating the female body as capable of experiencing both autonomous physical desire and spiritual transcendence. In this fashion, the relationship between Lucy, Jane, and supernaturalism constitutes a rejection, or at the very least a tempering, of the Christological monomyth that dominates Western literature and thought. Both Jane Eyre and Villette establish the female body as desirous of erotic fulfillment, and the female mind as desirous of spiritual ascension. Charged with the impossible task of forging religious identities that do not compromise their agency, as well as achieving positions of gendered and sexual autonomy that do not compromise their faith, Lucy and Jane each provide complex and engaging insight into the various convolutions of divinity, femininity, and supernaturalism within the Victorian Gothic; the supernatural and mystic elements of their narratives simultaneously echo and interrogate the greater political questions surrounding feminism and spirituality that permeate each text.

Works Cited

Brontë, Charlotte. Jane Eyre. Ed. Stevie Davies. London: Penguin, 2006. Print.

Brontë, Charlotte. Villette. Ed. Helen M. Cooper. London: Penguin, 2004. Print.

Davis, Robert A. “Buffy the Vampire Slayer and the Pedagogy of Fear.” Slayage: The Journal of the Whedon Studies Association 1.3 (2001). Web. 21 Nov. 2015.

Johnson, E. D. H. ““Daring the Dread Glance”: Charlotte Brontë’s Treatment of the Supernatural in Villette.” Nineteenth-Century Fiction 20.4 (1966): 325-36. JSTOR. Web. 22 Nov. 2015.

Lorber, Laurel, “Haunted by Passion: Supernaturalism and Feminism in Jane Eyre and Villette” (2013). Seton Hall University Dissertations and Theses (ETDs). Paper 1889.

Warhol, Robyn R. “Double Gender, Double Genre in Jane Eyre and Villette.” Studies in English Literature 1500-1900. Vol. 36, No. 4, Nineteenth Century (1996): 857-75. JSTOR. Web. 21 Nov. 2015.

Wein, Toni. “Gothic Desire in Charlotte Brontë’s “Villette”” Studies in English Literature 1500-1900. Vol. 39, No. 4, The Nineteenth Century (1999): 733-46. JSTOR. Web. 23 Nov. 2015.

charcoal and #2 pencil. november, 2015. (unfinished).

Were you exasperated and disgusted by her, as an extreme form of yourself? Your wild talk, your turbulent moods, your ‘dark places’? Mental illness frightens you, like a contagion.

Joyce Carol Oates

To watch me love another is to gain insight into the many complex ways in which I may still hate myself. I am reckless. I am desperate. I am provocative. I am extreme.

I know a capacity to give myself away that transcends age, gender, circumstance. When I do so, I crucify myself on each detail: in rushes of intolerable empathy laced with egoism, I impale myself on the subtleties of another’s existence. I feel everything. I have to. Why else would I climb each cross so willingly?

Maybe underneath it all, in the secret core of our cowering souls, we all crave subjugation. I dread every new morning, every self-reproaching glance in the mirror, my own chastising gaze. I navigate convoluted prisms of desire, performativity, and shame. What new horror have I inflicted upon myself? What will I have to live with today?

To reduce my writings to “commentary” on any one person, place, or event, is to misconstrue entirely the nature and the purpose of my work. To speak more clearly: I do not write this in response to any particular element of my present life. I am as happy now as I ever have been, or perhaps ever can be. The plane upon which my writing operates differs greatly from whatever reality textures my daily existence. This is not simply a piece about “my life.”

No, this is the litany of a violent soul in stasis and a mind only slightly unhinged: with no circumstantial catastrophe to engage it, such energy inevitably devours itself. Unexpectedly, but not inexplicably, I am reckoning with the turbulent forces of a mind and a conscience that I always thought I understood. My work is antithetical to my sanity; my art enters into a conflict with myself.

I am thinking on symbols and sensuality: I must live within a language that is no longer my own. An ancient sacred agency was taken from me, while rhythms and rituals recall what I am. And what I am is a neurotic, in the most organic sense. I wish to be open. I want pleasure, tenderness, and melancholic dissonance to infuse my volatile soul. I am not adjusted to the world—I am adjusted to myself. I crave ecstasy, and when this life offers less than I can endure, I engage in relentless acts of self-consumption. I am both satisfied and insatiable, drenched in a certain desirous impulse, the specter of which haunts this visceral consciousness.

How, after all, can I experience an entire world, so vast and mercurial, through a single body? The inimitable allure of literature and of music in the streets: the sheer stimulation of these people, this place. I can play a guitar until my fingers bleed, but sensation still boils beneath the surface of my skin. Self-mutilation is only a memory now, never to be revisited—but in moments of almost unendurable ecstasy, I sometimes imagine that if I were to open my own skin once more, my inner self would be revealed not in anemic drops, but in radiant prisms of light.

I will never love anyone the way I loved my father. No one will ever love me the way my mother has. Some people are intrigued by what I present to them: they want to interrogate it, engage with it. But who would ever stay? What person could reckon, willingly, with the violence of what I am? At the extreme risk of self-debasement I engage wholly with my own passionate impulses. If I do not take myself seriously, who else will or can?

And so I am, in some ways, a narcissist. It is not the person that matters to me, but the figure: its relevance, its positionality and calibration within my life. My egoism is empathetic: my love is rapid and deep, but directionless. I cannot yet (or can no longer) emulate that mature, private, constant adoration that constitutes a “stable ideal.” I cannot always feel this way. I will forget this sensation, but will remember experiencing it. And then I will forget that too. My present self will be explicable, but not justifiable, to whatever I become.

In the ardent haze of summer, I knew an artist, and in an erotic act of desire, decision, and resilience, she painted me. This was a piece about womanhood, about ecstasy, about me. Across the top she wrote “Always,” and being who I am, I believed it. Sometimes I still do.

But just months later, I wandered autumnal streets slick with rainwater and lamplight, with a young man who was both disarmingly vulnerable and fascinatingly inaccessible. He had a mind that was captivating and disarrayed, and expressive, deep-set eyes the color of morning. In his sanguine, gentle consciousness, I misremembered myself. I knew a different kind of tenderness than that which had preceded him.

One morning, I awoke to glass windowpanes slick with frost. On the floor beside the bed, pale light had fallen across our garments. They were strewn across the painting, which lay on the floor where I had left it unfurled. I stared at the soft, stained fabrics that belonged to me: fragile lace, crimson in color, precisely the same shade as those tenderly bleeding words. Always.

Beside me, another body, the geography of which I had explored beneath my fingertips like every one before it, was sleeping soundly, breathing softly, knowing little, caring less. A sensual dispersion of paint across canvas, that passionate memory of lesbian desire: it seemed so strangely at odds with the cast-off clothing of the woman it had memorialized, and the young man now asleep in her bed.

It was pretentious, it was absurd, but for the briefest moment I felt older. Like I had lived and loved a lifetime’s worth. I felt tired and I felt alive.

Then I realized that I had forgotten the precise color of her eyes. Well fuck, what then?

Yes, it fades, it always fades: all I ever need is another figure, another body, another site of imposition for the discursive passion that colours my mind. Sometimes these desires replicate in my own physicality: another cigarette, another skipped meal, another sleepless night. I pace the silence at the edge of my bed until I hear my name drop softly from another’s lips. It is as beautiful as it is damning. I remember everyone that I meet.

Ancient cities of intellect and romance constitute a peculiar sense of home for the woman who wanders their capillaries. Spires dream and I am wide-awake with the morning. Cobblestone streets work their way into the contours of my soul.

I am growing, changing, becoming. I feel too deeply. No body can contain me. I cannot be alone—not ever. Except that I already am. I always have been. I consume (and in doing so nourish) myself.

The sun had not yet fully risen in the sky when I locked the bathroom door behind me and stared hard at my reflection in the mirror. His breathing fell like rain against windowpanes, echoing through my mind on that cold grey morning; and as I slowly took in the guarded eyes, half-shaved hair, and scarred skin of the girl standing before me, there was nothing left to do but wonder what the hell had happened to her, and when.

In his critical commentary on In Memoriam A.H.H., Christopher Ricks refers to Alfred Lord Tennyson’s sentiments towards Arthur Henry Hallam as a love “passing the love of women” (Tennyson, 332). The implications of this phrase are multitudinous and significant: in the body of work that Tennyson produced following Hallam’s death, the relationship between the two men became a primary contextual backdrop against which some of Tennyson’s finest poetry could be read. The queer-coded elements of Tennyson’s writing provide insight into his complex negotiation of sexual and gender identity in the heteronormative confines of Victorian England, with subtextual expressions of homoromantic impulse lending a subversive quality to In Memoriam, while an intricate depiction of gender and power dictates the narrative of The Princess. The conflation of desire and convention in these two poems generates tension between the cultural norms of Victorian England and the social worlds of the texts, providing the thematic foundation for larger discourses surrounding gender and sexuality in both works. Between the latently queer desires of In Memoriam, and the deeply gendered discourses of The Princess, a nuanced representation of passion, power, and masculinity within Tennyson’s works can be observed and understood.

An understanding of the socialized imposition of compulsory heterosexuality is imperative for expanding and reexamining the critical discourses that surround western literature; its demonstrable presence in the poetry of Tennyson bears specific relevance to the notion of Victorian masculinity, and by extension, to the formulation of intimate relationships between the men of Tennyson’s time. Indeed, the most notable shortcoming of many heteronormative readings of In Memoriam is their failure to fully account for Tennyson’s observable passion for Arthur Hallam. Many critics have attempted to circumvent the potential implications of homoeroticism by constructing a sterile narrative of friendship between the two men: Gordon Haight, for instance, argues that, “The Victorians’ conception of love between those of the same sex cannot be understood fairly by an age steeped in Freud. Where they saw only pure friendship, the modern reader assumes perversion… Even In Memoriam, for some, now has a troubling overtone” (Ricks, 208). Of course, a certain level of homophobic subtext is evident in the very language of Haight’s assertion: the identification of queerness as “troubling,” and of potential same-sex desires as “perversion,” lends little credence to the impartiality of the observation at hand. The more relevant flaw in this reading, however, is its erroneous presupposition that heterosexuality exists as an organic norm through which a complete understanding of all interpersonal human relationships can be achieved. This narrative of ‘natural’ heteronormativity discredits substantial historical and cultural evidence to the contrary: as Adrienne Rich identifies in Compulsory Heterosexuality and Lesbian Existence, “The failure to examine heterosexuality as an institution is like failing to admit that the economic system called capitalism or the caste system of racism is maintained by a variety of forces, including both physical violence and false consciousness” (Rich, 648). A queered reading of Tennyson is necessarily cognizant of the fact that compulsory heterosexuality, particularly as it appears in western culture, is a product of oppressive and oftentimes violent socialization, and does not necessarily reflect a ‘pure,’ ‘natural,’ or accurate state of being. With this in mind, a reading of Tennyson’s poetry that willingly engages with its homoerotic subtext is academically as well as politically relevant; far from being narrow or limiting, such resistance to preexisting structures of compulsory heterosexuality can in fact broaden the parameters of discourse that encompass Tennyson’s poetry as a whole.

In Saint Foucault: Towards A Gay Hagiography, gender and queer theorist David M. Halperin writes, “Queer is by definition whatever is at odds with the normal, the legitimate, the dominant. There is nothing in particular to which it necessarily refers…. Queer demarcates not a positivity but a positionality vis-à-vis the normative” (Halperin, 62). This notion of relative positionality is evoked through metaphor in In Memoriam, when Tennyson writes, “O Sorrow, wilt thou live with me / No casual mistress, but a wife” (Tennyson, IM, LIX 1-2). The conceptualization of Sorrow in these lines, as an emotion so prevalent as to actually become anthromorphized within the text, demonstrates a relative existence: her presence within the poem is necessarily contingent upon the absence of Hallam, because it is Hallam’s death that generates Sorrow to begin with. The heterosexual nature of the relationship between Tennyson and the female-coded Sorrow, then, is similarly relative: as Jeff Nunokawa observes, “[Tennyson’s] heterosexual situation is thus defined as the ghost of prior passion” (Nunokawa, 429). In other words, the notion of Sorrow as “wife” constitutes a heterosexual positionality that exists in relation to whatever preceded it; the implied specter of marriage in these lines contrasts the relationship between Tennyson and Hallam not only through its contingence upon Hallam’s absence, but also through its gendered situation relative to the homosocial relationship that predates it. Tennyson goes on to proclaim of Hallam, “My spirit loved and loves him yet, / Like some poor girl whose heart is set /On one whose rank exceeds her own” (Tennyson, IM, LX 2-4). By feminizing his narrative self, Tennyson constructs an image that simultaneously reproduces and subverts heterosexual norms of affection. This sense of homoromantic desire is further echoed through the rhythmic structure of the poem as a whole: Tennyson’s use of iambic tetrameter lends In Memoriam an organic, bodily cadence that underscores the poem’s foundations of passion.

The queer undertones present in this reading of In Memoriam are simultaneously complicated and informed by Tennyson’s regressive treatment of gender in his other works. The Princess takes on a particular relevance through its status as an oddly subversive, yet ultimately antifeminist text; although varied and nuanced discourses surrounding gender take place throughout the narrative, The Princess fundamentally devalues the feminist principles it discusses through its narrative prioritization of heterosexual male desire and emphasis on female submission. The treatment of gender within The Princess is nevertheless uncommonly nuanced; in her 1990 book Gender Trouble, Judith Butler writes, “…gender is not to culture as sex is to nature; gender is also the discursive/cultural means by which “sexed nature” or “a natural sex” is produced and established as “prediscursive,” prior to culture, a politically neutral surface on which culture acts” (Butler, 7). This notion of gender as a fluid and in some senses performative construct emerges repeatedly throughout The Princess: many of the poem’s male characters are coded feminine, with the protagonist himself described as, “Of temper amorous, as the first of May / With lengths of yellow ringlet, like a girl” (Tennyson, TP, I 2-4). Furthermore, in the course of the narrative, the Prince and his companion assume women’s clothing in order to gain access to the Princess’s exclusively female spaces. Through Tennyson’s description of this subversive action, the binary notion of gender is simultaneously transgressed and reinforced: the ability of the Prince and his companion to pass as women emphasizes the performative nature of gender, but also underscores the vast differences between the men and women of the text. By the end of the poem, the success of these masculine efforts is evident in the romantic submission displayed by the Princess. In light of this, although it seems to occasionally examine gender as a mutable state of performativity, The Princess ultimately fortifies, rather than disrupts, the oppressive structures it seeks to address. The poem as a whole is irrefutably male-centric, introducing elements of feminist discourse, but undercutting them through the events of the narrative. As Donald Hall asserts, “In The Princess we find enacted a zero-sum game of gender and power; men can only regain consciousness and, by implication, potency, when the empowered woman is subdued and male ability exalted” (Hall, 55).

The relation of gender identity and antifeminism in The Princess to the politics of sexuality in In Memoriam is primarily observable in the complex reading of Victorian masculinity that both poems offer. In The Embodiment of Masculinity, western masculinity in is observed as being “defined in opposition to all things feminine” (Mihskind, 103). This ideal naturally entails the disavowal of queerness in men, as compulsory heterosexuality would categorize sexual or romantic attraction to men as the provincial territory of the female. Sociologist R.W. Connel explains that, “To many people, homosexuality is a negation of masculinity, and homosexual men must be effeminate… hegemonic masculinity was thus redefined as explicitly and exclusively heterosexual” (Connell, 736). When read through a cultural lens of heterosexual male hegemony, then, Tennyson’s writings involve a self-contradicting performance of masculinity: the poet rigidly reinforces systems of gendered subjugation in works such as The Princess, even as latent homoerotic desire forms the perpetual subtext of his most famous work. In this fashion, the undertones of In Memoriam, coupled with the narrative of The Princess, form an intricate nexus of desire and power that characterizes the gendered and sexual ethos of Tennyson’s work: compellingly queer and irredeemably antifeminist, the two poems shed light upon the contradictions and complications of subversive masculine identity within Victorian England.

Works Cited

Connell, R. W. “A Very Straight Gay: Masculinity, Homosexual Experience, and the Dynamics of Gender.” American Sociological Review 57.6 (1992): 735-51. JSTOR. Web. 16 Nov. 2015.

Hall, Donald E. “The Anti-Feminist Ideology of Tennyson’s “The Princess”” Modern Language Studies 21.4 (1991): 49-62. JSTOR. Web. 15 Nov. 2015.

Halperin, David M. Saint Foucault: Towards A Gay Hagiography. New York: Oxford UP, 1995. Print.

Mishkind, Mark E., Judith Rodin, Lisa R. Silberstein, and Ruth H. Striegel-Moore. “The Embodiment of Masculinity: Cultural, Psychological, and Behavioral Dimensions.” The American Body in Context: An Anthology. By Jessica R. Johnston. Wilmington, DE: Scholarly Resources, 2001. 103-20. Google Scholar. Web. 15 Nov. 2015.

Nunokawa, Jeff. ““In Memoriam” and the Extinction of the Homosexual.” ELH 58.2 (1991): 427- 38. JSTOR. Web. 15 Nov. 2015.

Rich, Adrienne. “Compulsory Heterosexuality and Lesbian Existence.” Signs 5.4, Women: Sex and Sexuality (1980): 631-60. JSTOR. Web. 17 Nov. 2015.

Ricks, Christopher. Tennyson. New York: MacMillan, 1972. Google Scholar. Web. 16 Nov. 2015.

Tennyson, Alfred Tennyson. Tennyson: A Selected Edition. Ed. Christopher B. Ricks. Harlow: Longman, 1989. Print.

© 2025 Forms of Boredom Advertised as Poetry

Theme by Anders Noren — Up ↑

Recent Comments