Some shape of beauty moves away the pall

From our dark spirits.

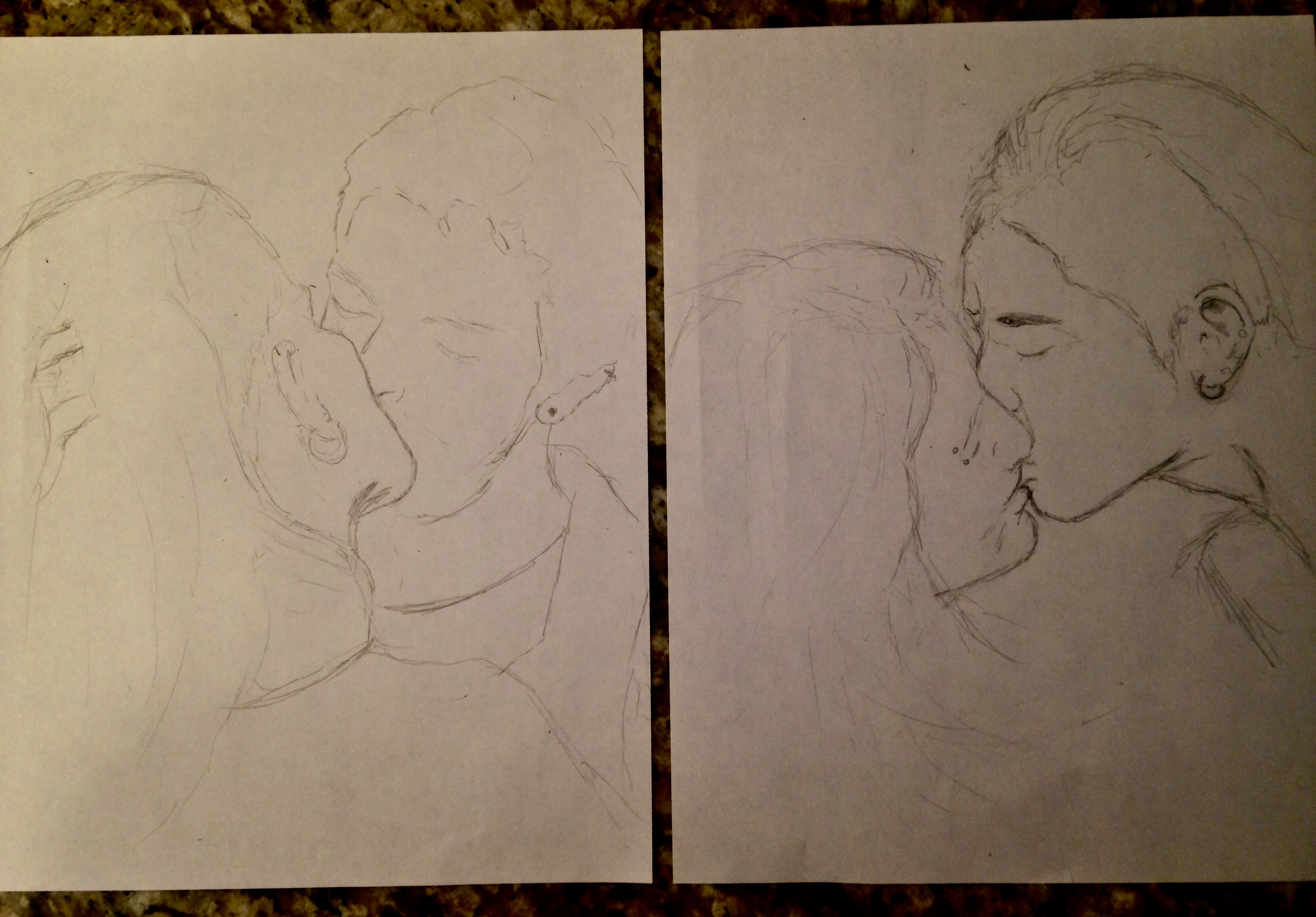

charcoal, #2 pencil, and HB and 6B graphite. july 16, 2016.

How odd I can have all this inside me and to you it’s just words.

David Foster Wallace, The Pale King

The summer has passed me by quietly so far. I am realizing lately that I rarely, if ever, write in my authorial (rather than narrative) voice. What I mean is, I don’t write in the same way that I talk (so to speak). What does that say about how I see myself in a social context? (That was rhetorical: don’t answer it).

Do not misunderstand me: my narrative voice is not—in my eyes, at least—contrived. It is not an obscuring of myself, but an actualization. I use language, become as verbose as I feel necessary, in order to engage with content that I otherwise regard as nearly unspeakable. It feels organic. It feels like a truth. Even so, I am a person and I write about people. When I allegorize each experience, I am only providing half of the story.

Every now and then, in some conversation or another, someone (and I can tell you every name and what they said, because these are some of the most humbling moments it is possible for me to have) will reference my blog while talking to me. Sometimes they mention specific phrases or images or ideas. Once, an attendant at a house party quoted a piece verbatim (that really tickled me). Every single time this occurs, it never fails to astound me—and I mean literally astound me—because with the exception of a few scattered “likes” on Facebook, I genuinely can’t believe that people actually read this blog.

And that might be for the better: I think I have to believe that. My literature (so to speak) is a full-on, unflinching chronicle of a mental state that sometimes seems to be deteriorating at a rate that frightens even me. What might it mean to know this, to see myself as being seen this way, as a thing that has spent half of this year one wrong word or thoughtless action away from a complete breakdown? I could hardly stand knowing that people knew me in this way. I have to believe that, as I work towards regaining much of my health, many of you are choosing not to look.

Do “people,” in the abstract—that is to say other people, people outside of myself and those that I know intimately—understand how much I like them? Not just as individuals, but as a notion, as people-who-are-not-me. I am fascinated by this whole living, breathing, thinking network of human bodies that all seem to know what they’re doing when I don’t. I want to be fond of it. I want to break down all of the unspoken barriers that seem to impede my relation to some greater world.

But to really grasp the difficulty of achieving this, one would first have to understand why I built up such remarkably effective walls in the first place. And I’m not sure even I really understand that.

I don’t think I was all that well-liked as a kid. I’m fairly certain that has something to do with it. Losing my relationship with my dad probably didn’t help either. But I never realized just how bad things were until the end of my first year at university. Now I am trying to remember the last time I felt completely comfortable in a social space full of other people—the last time I did not feel an implicit need to justify what I perceive as the inherent detriment of my presence—and I honestly cannot.

To be clear, this is not a new issue for me. One of the clearest and earliest memories I have of this, outside of family events and classroom settings, occurred when I was thirteen years old. I was enrolled in a summer theatre program that was, in my eyes, the single most wonderful place on the planet. I had never been more excited. It was not always easy for me: with a nonverbal disorder, chronic anxiety, and some symptoms of potentially being on the spectrum, I was unable to navigate the fast-paced and exhaustingly social atmosphere of the camp as easily as I might have liked to. Sometimes I spoke too much or too loudly. Sometimes I was too nervous to speak. Nevertheless, I was extremely happy. I was so thrilled to be there, in spite of its challenges, that to this day I am not completely sure what I was doing wrong.

But I must have been doing something, because one day, the program director asked to have a “conversation” with me. My memory has expunged most of the encounter—to protect me, most likely—but I remember that she said something about behavioral complaints. Then she asked me, very seriously and sternly, if someone was making me come to the program every day. That question hit me much harder than I am sure the poor woman had intended for it to. To her utter surprise and confusion, I began shaking, then crying hard.

“No one’s making me come here” I choked out, “I want to be here. This is my favorite place in the world.”

I will never forget that feeling. I was hurt and I was humiliated, but worst of all, I was crumbling beneath a sense of woeful and staggering inadequacy: not only, in my thirteen-year-old mind, could I not get these people to like me—I had somehow also failed to communicate how very much I liked and admired them. When I went home that day, I had cried all of the shock out of me, and so I sat in my room for hours and did nothing at all. When my parents came home, I did not tell them that anything (or everything) had gone wrong. I spent the next day stammering out explanations to anyone who would listen. I spent the rest of the summer apologizing everywhere I went.

But the conversations continued. Things just kept happening. And it all hurt tremendously, but how were they to know? They were all so well intended. They were trying to help by fixing me. But I didn’t need fixing. I needed someone to like me. I needed one goddamned person to understand how confused I was by the world. But that person never appeared, and at some point, I think that I just started assuming my own inevitable isolation. I wanted to become untouchable, and thus, less damageable.

So I got smarter. I worked my ass off in high school, and better yet, by the time I reached eighteen or so, I learned how to make it look as though I was not trying at all. (That’s bullshit, by the way. I am always trying very hard, and usually just in the interest of keeping my head above the water). I got angry. I started smoking, mostly so that my hands would stop shaking every time I tried to make conversation with a classmate or a shopkeeper or a stranger. I inked my skin. I shaved my hair. I learned how to argue with, dismiss, and mistreat other people. You could say that I learned to make them feel how they used to make me feel.

But that is the problem, isn’t it? These people aren’t all the same person; yet I began, ridiculously, to forego their demarcation by the inevitable virtue of their not being me. I saw everything in a manner that was almost explicitly oppositional: there was Myself, and then there was Everyone Else. And I was in equal parts envious, suspicious, contemptuous, and admiring of Everyone Else, simply because They were not Me. I still struggle with this.

Not all of the changes were detrimental, of course. Some of them were revelations, rites of passage, my means of coming into a better and fuller sense of personhood. The issue arises, I reckon, when I am no longer confident in my ability to differentiate between the protective spectacle and the unrestrained self. Because when your mind falls apart and your fingers are always twitching and you wake up one morning and realize that you have lost just about every trace of the optimism and vulnerability that you used to have in abundance, it is easy to be bitter and resentful of the world.

Is this helpful, though? Am I healing? If the last year is anything to go off of, then the answer is absolutely fucking not. The unhappy moments I describe have been internalized, by me, as lasting and deeply harmful parts of my psyche. They compounded with early strains of my depression, and years of verbal and psychological maltreatment, to such a damaging extreme that my therapist and my psychiatrist and my team of doctors finally produced another diagnosis to add to my nightmarishly accomplished mental repertoire. They gave my paranoia a new name, they called it Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, they wrote a few new clinical notes, and provided some impassive words of sympathy that dripped into my skin like anesthesia. It made me feel so fucking low.

Now, I am desperately seeking someone or something to hold onto. I am pushing away everything that I do not want to hurt, or that I do not want to lend the power to hurt me. I am not always doing the right thing. But if there is one thing I will credit myself for, it is that I did at least try to communicate what I was thinking and feeling. Yes, sure, maybe it was not enough. Maybe people really did not know the full extent of the damage they inflicted when they leveled unfair and untrue accusations, when they left me alone in the worst parts of my life, when they failed to stay in touch, when they made me start hating myself again. But they knew, they must have known, that I was violently ill. I wore it on my arms and my protruding ribs. I stopped laughing. I stopped working. I stopped going outside. And most unmistakably, most explicitly, I allegorized, documented, and published it all here. On this blog.

Does this read like I feel sorry for myself? That might be because I have nothing left to lose from self pity. I did everything I was supposed to. I “got help.” I tried to be honest. I fought back when I had to, and when I saw no other option but to be angry and unrepentant, that is exactly what I was. (Why is that so often construed as fucking funny, by the way? Why does it amuse people to see me so obviously upset: online or in person? What difference is there between aggravating my fears for entertainment and kicking a goddamned dog? If I remember the last incident correctly, there are 27 of you who might explain that difference to me sometime). I was ill to the point of incapacity, and it was overridden and ignored. My needs were overlooked and displaced in favor of a more greater and more comfortable social narrative wherein I was making some active choice to feel this way. But that wasn’t true, it just wasn’t. A half informed conception of my personhood was projected, perhaps inflicted, upon my scars and my episodes with a relentless and unforgiving precision.

Is it my fault, then? I know that it might be simpler, less painful, to comply a bit more. But I don’t see that it’s any better to kill myself slowly, in pieces, by behaving like a thing I am not, rather than simply taking care of it all in one permanent action. With any luck, this will remain a choice that does not need making. But do any of you really understand, for a even a goddamned second, what really compels me to write the way I do, and as often I do, and using the subject matter that I choose? I am not all that talented or thoughtful or insightful. I am just trying to justify my own presence, because I don’t think my presence is, on its own, justifiable. And I did not come to feel this way needlessly.

I want to be like everyone else. I want to be treated as normal. But I also need people to understand that, for me, it is a herculean effort to get out of bed every day. I can be wrenchingly honest about the fact that I am angry and sometimes hardly sane. But I am far less forthright in addressing the fact I am just sad, or sick, or scared sometimes, and it is not a cataclysmic tragedy, but a very simple and fixable problem. The “Confession” here, then, is that I am not special. I am just relentlessly sensitive, irrationally melancholic, and chronically unwell. The confession is that I believe, secretly, that most of you already knew that, and that my constructed narrative of feeling misunderstood is just a way of not having to face being understood and yet uncared for. This is everything I was too afraid to say; it is the exorcism of what I was taught not to speak of or remember.

I am trying so hard to negotiate some form of existence that does not feel like it is killing me off. I am trying to live an impassioned, compassionate life. I am trying to be likable. I am trying to love. If there is one action that I must resolve myself to, it is the critical and continued interrogation of my impact on other people; the influence I have by sheer virtue of speaking, moving, engaging within some space that is not my mind. Because that is how I will endure this. And I would prefer not to do so alone.

…and there was the sea between us again.

(Sylvia Plath, “The Unabridged Journals”)

#2 pencil. july 14, 2016. (unfinished).

Tell me, how does it feel with my teeth in your heart?

Euripides, Medea

I clawed my way back from a pulse’s periphery, bearing the visage of some creature far from health. I returned to an unwilling existence, feeling so selfish and so sorry. I took a bus into the city, found you amidst the shop-strewn streets. I walked you home. You slept beside me. I let the night run quietly through my mind.

In those hours, I thought that the worst must be over. But it was only beginning—and I, of all people, should have known that. Mine are the botched efforts of an unhinged, half-formed child: I honor my mother with callousness and a trail of broken things. Dim figures break their lingering promises; I break their lovely, blistering hearts; we break whatever sinew still tethers us to sanity; I break myself upon them. I have no innocence, no reverence, I am wretchedly aware of it all. But I am still willing. Oh yes, I will own this. I mean to be a horror-show lover, filled with half-furious remorse—but never to lose twenty-five years of life to a thing that means to leave me. Not another bastard God. Please, please, give me anything but that. I am sick half to death of failed deities and absent Fathers and false saviours: once, I imbibed his brutal adoration like a toxin, anointed in trilemmatic despondency, drinking each sacrament with consecrated helplessness; but I will not be mute or virtuous any longer. I will be faithless in totality. I will know no master but my own will to live. My efforts will likely be successful, but their victory entails my dissent, my infidelity, the unholy utterances of an absolute freedom. I will be secular: I, who wants more than anything to atone. What could be lonelier than that?

In the end, my love, when it all was said and done, I only needed a promise. I only wanted your mind and your time. I only drove you off because I hoped so desperately for to you to stay. Of this, I am unrepentant. You used to like when I acted that way, waking with the morning, pushing my fingers through your mouth, your throat: the muscles moved, the joints unfurled, and thereupon, a language lay inscribed. I wanted and wanted and wanted you: I engendered meaning in diacopes of desire. When you responded in turn, it was ecstasy, a miracle: those words were the genesis of our better days. I imagined, then, that I was free to do and to write as I wished. I presumed that I was justified by the mere act of loving you. I was not.

When the first blood of our carnal clauses was still drying like a cipher between my thighs, you lost the ability to read me. Those movements that you once thought so beautiful, so coherent, were a dead language to your mind. I might never know any skill with which to articulate what uncertain misery then unfolded, what catastrophe born of Babel drank the fluency from your tongue. Your lexicon, your literacy, the longings you derived—they came undone around us, inverting like rhythms of a chiasmus, until we were only the specter of our own discontent: loving what we could not keep, and keeping what we could not love. Our intentions turned in phrases, like hands on the face of a clock: we orbited one another in nameless, effaced wants. But there were not enough moments: I needed more time. I thought that you were coming home, but you never did. The absence of your demarcation flooded me with fear, immersed me in oppressive and somatic plentitude. The idioms faded fast from my many incisions, the agonized intaglios of my need for normalcy, the calligraphy of knotted scars that you once read like braille beneath your hands. Text and body met in incomprehension, showered in shades of your disavowal. Yearnings clashed like prosody. Why did you stop choosing me?

Your gentle mouth with its barbed tongue and clauses slick with chrome,

Now excavated and bit back the palace of my bones

You gnashed and ground and gouged your teeth all through my sob-torn chest:

The crypt-like, cracking cartilage that caged my dying breaths.

You started then my work for me, the rest I did in bed:

Crouching in the darkness, grief-raw memory rusted red

I held out that feral thing, forsaken, soaked with brine—

And ate of my own heart, for it was bitter: it was mine.

I never understood it. Why did you not wait for me? I gave you my reverence. I gave you my rhetoric. I needed you more than my memories, I showed you a longing that surpassed language. Do you remember when the sheets were soaked with my suffering: when I allowed you to rest your head against this heart as it wrenched and raced with a chemical burn? That is what it looks like when, in spite of myself, I try. I always thought that if I held fast to your form, sank my fingernails into your mind, gave you blood and bliss and fortitude, then you might remain for just a little while longer. An astrology of scar tissue; the scorched starlight of my empty soul—I offered this cosmology to you alone. Those bandages, clean and whiter than a narcissus, I only applied so that I might meet your eyes. You saw so little, but did you suspect? You were the only desire I knew in the end. Why did you not wait?

A year or so ago, when I was young and enthralled, when I still had my memories and some reason left to lose, I fell in love with a longing made manifest. Back then, my body recalled cheap hotel rooms and unlit cigarettes and the kind of nights that flow like delirium into the mornings, and I gave it to him, understanding it to be everything. I undressed to my necklace, a bare-hearted girl in a silver chain: shivering skin, narcoleptic memory, undone desires, long ragged hair. I thought I loved him. I can still feel those hands upon me. I wanted him to tear the tarnished thing from my throat. If he had meant to hurt me, then I would have known pain. That was the choice I made. I thought I loved him, I honestly did. I wanted to be pure. What an exquisitely vicious mind I had.

This world was not built to sustain the inclinations of a half-devoured heart. It is too pragmatic. It is too sane. And I, love, wear affection like pathology: I am indifferent when and where it counts. I did not mean to frighten anyone, when I clambered half-conscious and barefoot atop that roof, the wind cutting hard against my scalded arms, the concrete calling out like a promise. I simply sought to be empty: to lie back, skin stripped raw, bare hands upturned beside an expressionless face. I saw nothing wrong with this; even now, I see precious little. But they mean to send me back to those rooms all the same, with their blank walls like blindness, because my dreams are bad, and getting worse. My skin is riddled with bullet holes, a wounded, skewered thing: my body dances on splinters of glass, and treads upon rows of teeth in the earth. Blood falls fatal from your mouth, your flesh undone beneath my touch; you turn away from me. I thought I lost you once before—now I lose you every goddamn night. It is not getting any easier. Yes, the dreams are bad.

I spent a year of my existence in some purgatorial nightmare of social life. I felt unwanted. I felt ashamed. But I cannot do it anymore: I will not comply. I no longer have any use for their scathing standards. Fuck them. I am not writing for them. I am not a fucking martyr. I am not an object of their sympathies. I am not an image of tragedy, and I will not be compliant in another tragic act. I am an ego in constant opposition. I am bitter. I am angry. This world has failed me, it asked too much. I am nothing but a body now. I am this, and only this, whatever the hell “this” is—all else is Other. And how can I tell the goddamned difference? Everything, everything, antagonizes me.

This mind is an enigma, engaged in some perpetuity of motion. It knows so little. It barely even knows itself. But a lifetime ago, however briefly, however intemperately, I know that it knew you. It longs to hear your voice again: your contrapuntal promises, the staccato of your nomenclature, the evasive keys of a symphonic longing, the crescendo of your night-tinged scores. I remember, so fondly and sorrowfully, all of the times when I wanted to hold you or kiss you or fuse my heart with yours: to take whatever parts of you were tired, or hurting, or afraid, and endure it all in your stead. But I did not know how to, or if you would allow it, and so I stayed as mute as the child I no longer am. I wish that I had tried. I wish that I had silenced, with my mouth and hands, every doubt in your unquiet mind. I should have consumed all of that suffering until the only thing you felt was my skin. I should have taken care of you.

Darling, I have had my chances. I know what I am. I know that, in our ending, I lost something that I may not soon find again. But for what it is worth, I adored you. We liked to pretend that this was meaningless, but it was never, it was not. I will not accept even the suggestion of our insignificance. Nothing is without meaning, not in this life, and especially not us. We know that the world is in motion. We see how it births and dies. We feel, in our joined bodies, its constant burning. We were not thoughtless, but overcome by the brilliance of our being. I will always absolve you, by virtue of what you are. I willingly excuse the horrors you inflicted; I take them on gladly; I vindicate it all. I exonerate you of your false promises, your lost language, your perpetual absence, your notched and troubled ways. What did I ever do, in this godforsaken life, to earn such reckless affections? This is me saying that I love you. I love you; and you will never again, in all probability, be loved by a thing like me.

But I never owned you–would that I had–and when the waking spring finally drew to a close, it was I who crossed the distant sea. There is so little left to be written of us. But you do not have to worry about me. You never have to worry, for I am not the dying type. I am merely a parasite, devouring my own longings. I am sustained by the intolerable rhythm of my pulse; by the rust-tinted flood of the summer rain; by the lingering potency of a desire I mistook for God. I am a thing apart from sanity. I am an unrepentant self. It is as beautiful as it is appalling: I eat away at my own heart like some hateful, half-life Eucharist.

And what apostate, after all, has ever shied from a bloodletting?

“I am a wound walking out of hospital.

I am a wound that they are letting go.

I leave my health behind. I leave someone

Who would adhere to me: I undo her

fingers like bandages: I go.”

I exist in two places,

Here and where you are.Margaret Atwood, Corpse Song

It was a Thursday. I am almost certain of that. I was thinking about wars. They are everywhere, they were on my television set today. I struggled to engage, to endure the blank truths of the living world, but apathy dripped like static down the screen. I tried to care all the same. I want you to know that I tried.

And I missed you–I want you to know that, too. I felt your absence like a stillborn limb. That day, the white rooms were as quiet as light on water, and I missed you. The astral core of an iris contracted, and I missed you. The birds recited some babel-tongue song, and I missed you. The ocean gnawed at a cliff’s edge, and I missed you. The fireworks bloomed and I missed you. My brother smiled and I missed you. It was raining and I missed you.

I have always loved the shadows in my mind. But you, all of you, recoil: you draw back from the very mention of them. How can you hate such vivid parts of me? They are not always trying to kill me off. They can be so wonderful–you would not understand. It is hypocrisy, I think. You see these things hurt me. You feel that they should not. You protest their harrowing presence, and so hold the harbingers of my insanity to a higher standard than your own compromised selves. Stop trying to decide what to make of this flesh, this me. You know, in your heart of hearts, that it is not possible. Look closely at what I am.

Just the other evening, after yet another trying session, my senses became confused. They bit like frost and boiled with their own incoherence. So I wrote. I wrote about everything. I wrote about bed sheets, and their velvet felt lilac. I wrote about a girl I knew, and heard a softness like rosewater. I wrote about the piano beneath your window, and felt the winter I spent with you in gradients of E minor. I wrote about sex and it tasted silver. But when I tried to write about myself, about everything that happened this spring, I could only hear the shape of my bruises. So I stopped. I had to stop. It hurt too much to go on.

How can I learn what I am, when what I am is all that I ever thought I knew? There is still so much left to understand. What makes me feel like this? Why do some people stay? I sure as hell never planned to.

I am immersed in the caustic Atlantic: its eerie green-blues curl in toxic, foam-tinged tongues of brine. My consciousness drifts between two broken nations, seeking solace in both, finding respite in neither. I am disparate; separated, as they are, by ringing chasms of salt water and wind. There is not even the faintest hope of a homecoming for me. But sometimes it is all right to be here, in this place, where I am restless, reverential, half-haunted with the memories of some strange other life.

Exhausted, always, by this mind that flips like a tarot card, I watch the tortured dusk of the past take form. I feel you emerge, a chameleon: lips curled, air-eating. Your stomach glows the burnt-gold of embers that fracture under your skin. I cannot recall my own father’s smile, and yet I remember, with perfect clarity, the way your hands moved when you rolled cigarettes on the streets outside of a bookstore café. Your joints unfolding like poetry, the lightness when you laughed, the invaluable instances of tenderness, our apologies, my convictions, your entropy and bright, bright eyes. I know how these things felt, but I am already forgetting your voice. What does it matter, anyways, if I loved you at the end? Contention, contentment, condemnation, contempt: now I just want to drive my teeth into your throat and taste the warm-as-salt miracle of your skin once more. And I want you to want me to.

All of that time I spent fear-filled, striving to achieve some fiction of normalcy: those were the moments that I could have spent loving you. I am sorry for not knowing that. I am sorry for knowing it now. I am sorry that you loved a virus. I am sorry that I let you. But sometimes I think that I should hold your mind to the fire: extract a confession, a catharsis, a promise, a penance, from the tongue that I once held like communion between my teeth. Are you blameless? How can you be? I was dying, did you fail to notice? Sometimes, when I am scared or sick or sleepless, I ask myself, wretchedly, if perhaps you preferred not to look. For if you had, you would have seen me, you would have seen how unhappy I was. Deep in the innermost core of me, I suspect that you were too clever for your oversight to have been a mere carelessness.

But how can I ask you to suffer this: how can I want you to know, for any reason at all, what it feels like when the doctors cut into me? I could not even bring myself to make you look. I never wanted you to see what was happening to me. And how can I hate you, for not engaging, not trying to save me, when I would only have consumed each earnest effort, and become some parasitic thing: leech-like, useless, hateful even to myself? But look at me, really look. It is safe to look now–for I am irreverent, and I am far away, and you could not help me if you tried.

It is my fault too, you know. After all, I let it grow inside of me. Childless mother, nightmare that I am, I should never have tended to it. I should never have made it love me. And I never would have, not ever, had I known that I was to love you. I still remember that morning: the sky was clouded, shrouded in white. White like the narcissi, white as blindness: the flames licked at my wrist until I was cleaner than snow. But why did I hate myself so? Maybe some part of me knew. I wish that I had murdered it then, this thing that now murders me.

You never ceased to confound me, with your lovely brown eyes and your arresting phrases and your aimless wants and your steadfast ways. But you loved what I wrote, what I am. I should have held fast to that.

So what does it matter, really? You are not as she was: she had a a way of making me want her, of wresting form and expression from my reluctant heart until, wary though it had become, I felt willfully and ecstatically, imbued with a passionate vulnerability that all but silenced my astounded soul. And when she seared and scalded me, I knew her too well to draw back. I understood quite clearly what I had to do. It was not my love she needed. It was my language. And that was fine. I have enough words left to give, I think. I can barely face each day upon waking, but I could write for a lover like that until the night waxed sanguine and the stars fell burning from the sky. I could do it for you, as well. Do you want me to? Have you ever? Have you always? It could be both or neither. How very sightless I have become.

It matters not at all. This endeavor bears no purpose. This is a simple meditation on distance, on loneliness, on longing. Who is to blame for what I am? The soles of my feet are harder than cypress, and my soul is a diamond, corrupted by a spectatorial gaze. I enter the world like a lidless iris: a naked pupil, incorrigible and obscene. Drink, then, the pure blind blankness of my exposure. I am utterly lacking, I am as faceless as the moon. The eye, this eye, it is me: I am and am. So love what I forgot to be, this relentless, searching self.

Someday my mind will return to me–and I, my love, to you.

Consume my heart away; sick with desire

And fastened to a dying animal

It knows not what it is.W. B. Yeats, Sailing to Byzantium

Precious little time remained before I was to put the tides of an echoing sea between myself and this strange world once more. But in the hallowed space of those seven hours, it was finally worth it. I felt wanted. I was wanted. In every moment of that bittersweet night, I was precisely where I desired to be. The city was shrouded in starlight, imbued with the kaleidoscope of a stained-glass coming dawn and the effervescent fragrance of a champagne bottle between my lips. I was keenly aware of how wonderful it felt; the dew-garnished grass beneath my stirring form; the rain-washed pathways, sorrowful and glistening; the hands that ran along my shivering skin; the mouth so warm and sweet and familiar; the bed unmade with fingertips and teeth; his sighs like reverence, breathless and heady; the hushed velvet stillness; the dampness and heat. Spires climbed skywards, and diaphanous morning unfolded like an eyelid: dimmed with rose-quartz and rust. This was harmony at last, we had found the balance I had so long sought after, and it tethered us fast to that scene. I derived from his movements no intention that was not also my own: no desire but that which I felt as well. And so we moved forward into the exquisite, unknowable expanse of the night. We sustained something more than mere illusion. We learned the rare pleasure of forging a memory that quickens my pulse even now.

I was most alive when you were inside of me, not only in my body but in my mind and discourse. You calmed the part of me that makes me hurt, the part I am afraid of, that causes me to lose control. You did not cure me of my affliction, but you blunted its edge. Your presence was a sedative: I felt safe and calm, not narcotized but beautiful, insouciant, unmarred. It took half a year, of course, but it has come at last to this. I loved feeling you speak my name, watching your voice move across my half-shattered skin, breathing your final phrases as they carved patterns in the crystal refuge of my memory. And I liked your mind, so different from this which writes for you now: the gentle, pragmatic inclinations, the soft edges of sanity whereupon my caustic intemperance burned and curled. After every confession I offered, you kissed me. In our mutual acts of forgiveness and atonement, each glance resonating like a caress, we learned to know each other: we loved gently, recklessly, and all at once.

Of course, it could never have lasted any longer than one night, for that is the nature of what we are. In the early hours of morning, we met our end together, and I took my leave exactly as I had after that first, fateful evening: turning away from your watching form and wandering down the winding flight of stairs. You stood, for a moment, silhouetted in the doorframe, and your eyes cut into the very heart of me. How very different it felt, this time around. A lifetime or more had passed in the intermittent instances between our first and last goodbyes. Almost before you were gone, I was already remembering you, and melancholic, trancelike, I stood outside those doors and watched the solitary sunrise. I think you understood at last, that night, how I loved you in my own strange way—and that if I had ever hurt you, this alone was why. But what a pyrrhic victory it seems.

If you ever felt unwanted, I am sorry, I am sorry. I liked you. I admired you. But sometimes I hurt the things that remind me of me. I never meant to be this way. When I love a thing, it leaves me. When it leaves, I start to love it. I do not know which comes first. Can I only really care for that which makes me suffer—am I inflicting the horror upon myself? Is this paradox rooted in the fact that the things I love have always, eventually hurt me, or does it stem from my own unspoken love of hurting? My only conclusion, tentative though it may be, is that I never learned the difference between what loves me and what leaves. If my pain and my affection seldom seem separable, it is only because no one ever taught me how to distinguish one from the other. This is not my natural state. This is not a choice that I remember making. This is an ongoing act of mourning: a lived eulogy to my childhood, my father, my sanity, myself.

But this undifferentiated nexus of agony and adoration has wounded more than me. It is what allowed me to act, on occasion, with such obstinance. It is what drove me to recoil from moment after irretrievable moment. It is why I could not love you when I wanted to, when I could have tried, when there was still time, when you might have loved me in return. I cannot remedy that now—I can scarcely even learn from it, I fear. And therefore I am sorry, I am so entirely sorry; not just for failing to love you, but also for how very much I think I might love you now. I do not know when or how this happened. I have always been predisposed towards infatuation, unsustainable bouts of augmented feeling, but this took place so slowly, so naturally: it grew like ivy in my veins, it blossomed in my lungs, it took root in the history that we will always share. I never could have expected it. That garden that you realized, and that I wrote, has at last taken its full form. I found parts of myself there that I had believed were lost forever. I was the life in that nighttime, I was the growing thing: somnambulist, child, lover, transgressor, repenter, votive, desecrator—not just unhinged but unknowing, unknowable. I was living always in the liminal periphery between two worlds, purgatorial and profane. You witnessed within me the ineffable lightness and the enigmatic fire of my own being—for I was, in many ways, the object of my own impalement; not simply the crucified body, but also, perhaps, its cross.

I am crying. Finally. It has been so long since I have been able to feel in this way. I may regard this, always, as the year that consumed me—but I know that I am healing now, however slowly, however belatedly, because yesterday, I remembered what the rain feels like. In some ways, I am grateful that you were not always there to witness the fracturing of my health. I was not necessarily successful in surviving these months. I fell to pieces about as often as I endured; I was sometimes strong, and sometimes I was very weak. I am happy that you were able to experience, in our earliest days, the better parts of of me. I am thankful that you did not see me shatter. There was another for that task, and it only grieved her. I lent her, a while, the misery of this skin: she bore it well, but can I ever forgive us? I was so wounded, so undone, that I allowed myself to bleed out carelessly upon her hands and mind. She still believes in me, even now—but how can that possibly be? Sometimes I think that I should do penance for this, for showing her a love that I was not well enough to keep. I knew better than to feed off of a thing that could barely sustain itself.

But you told me not to live looking backwards anymore. I think, in this case, you were right. This world will not change. Not for me. And if I seem wistful or repentant now, it is only because I refuse to lose another beautiful thing to my tainted conscience or my guarded ways or my fading recollections. I have no pride left. I have conviction, desire, and defiance, but no pride. Not anymore. I am a nerve exposed. I am going to feel everything, if I can—I am going to feel it entirely and unashamedly. And so I will honor and write our final moments: because that is as close as I can come to recompense, to redamancy, to loving you in the way that you have deserved for so long now. I cannot retrieve what time and circumstance have now rendered a part of the past. But I can mourn this history, find beauty in its ephemerality; and above all else, I can remember you well. A kind of immortality resides in all language: it is what I have to offer in my body’s stead. And offer it I will, because at long last, I am on the way to knowing love, to knowing myself again. Those dusky, tortured, ocher months, when I was dragged back to life from its unwilling edges, are finally coming to a close. I am ready now. I want this.

These are the days of my healing. They entail so much more than any one person, time, or place. But they will always have been made possible, at least in part, by you. Because for one night, beside you, I felt fondly again. I remembered how you saw me, and so remembered who I was. And I am certain that counts for something.

If this was my baptism by fire, then I have survived it all. I will bear the scars and the scourges and the burns of these past six months for the rest of my life. But I will not atone for this any longer; instead, I will invoke the fortitude that you yourself taught me. I will requite the clemency and the empathy and the mercy that I have been shown—by you, by her, by all of them and more—not with penance, but with the restoration of my own health. It is time, I think, to rise once more, in tides of a burning lucidity, in clauses barbed with the bliss of a second coming. Whatever it takes, I will revive this body, this skin like a mutilated miracle: I will repair the branded arms and shorn hair and genderless desires. Eye my scars, then, and hear my heart. I will find life in exactly that which has consumed me: in the melted gold that floods the crevices of my bones, in the ash that trails from my fingertips. I will do more than just survive this. I will emerge, and I will enthrall, and I will make myself a thing worth knowing once more. So remember me, revere me, and watch what you have helped me to achieve. Watch as the consequences crystallize. Watch as I forge, from this grim history, something caustic and new. Watch as this promise takes on, like daybreak, another beautiful and terrifying form.

Watch me unfold with the smoke of my own burning.

Watch me begin to live again.

“Go back to sleep,” she murmured. “These aren’t times for things like that.”

He saw himself in the mirrors on the ceiling, saw her spinal column like a row of spools strung together along a cluster of withered nerves, and he saw that she was right—not because of the times, but because of themselves, who were no longer up to those things.Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

This is not a story about anything I have ever loved. This is a story about my illness, my undying anxieties, and the people I lost or never really had. This is just another chapter of the strangest year of my life, and it ends, as ever, with the specter of my earliest abandonment. But there was love there once. I did not always know this, but of late, I certainly have. So I am writing now in the sleepless delirium of another soon-to-be morning, with an overflowing ashtray and an onslaught of unwanted memories ringing through my tired mind. I am writing when I should be healing, because I am afraid that I have finally run out of time. After all, the spring has ended. I am crossing an ocean soon and leaving all of this behind.

Some of my best moments, the most clairvoyant and frankly erotic instances of my life, were spent in an unmade bed and the garden of my own discontent, where this branded body, all burned and scarred and wary, unfolded at last like a miracle or a mercy: engaging me, absolving me, rendering me close to whole. Those were the times that I never wanted to end, gazing down upon the form that I had come to regard so fondly; the two faces held between our four hands, knuckles entwined in tangled locks of hair; the mouth that moved in mine, tasting of something more permanent than pleasure; the ecstasy that echoed in reams of flesh, grazing against the sheltered depths of my self and my soul. I remember the abandon with which I allowed my spine to arch, arms crossed above my head, mind empty and fingers outstretched–and between my knees that half-crouching form, singular and impossibly beautiful. I felt then an elation so simple, a want so uncontrollable, that I scarcely recalled how to speak. My pulse was rapid and absolute: my body was singing that name. Does it matter what language one ascribes to such a sensation? Must it necessarily entail obligation or resolve? All I know for certain is that I was happy then. I was so entirely happy. It was one of the few things left here that could make me feel happy, that could make me feel anything at all. And I wanted to keep it until the end.

Then that time passed suddenly–two days, nothing more. All of the worst things happen around Father’s Day, I have found. So I expected something, I think, but certainly not this. That night was one of the worst in my memory. The catalyst does not bear retelling, but its consequences were instantaneous. I still do not quite understand what occurred, or why it so thoroughly undid me, but I could never have anticipated the sensation. I felt as though the utter heart had been ripped out of me. I was butchered and desperately hollow. I had seldom been so shaken, so confused, and there was nothing left to do except feel everything at once. I tried to reason with my own dissociated consciousness, but my mind had turned upon itself. I heard a laugh, a sound that scalded, and it fell like madness upon me–Left again, so soon?–until I finally slept, unquietly and afraid. That night I survived, if you may call it survival, the careless massacre of some precious drop of vulnerability that I did not know I had left to lose. I had not been aware, however scarcely, of its presence, until he bit that pretty thing in two and left me in an empty bed, drunk and dripping crimson.

Did I exasperate and disgust you, the furthest and most extreme form of what you fear yourself to be, laying bare your limitations in the extent of my insanity, the purgatory of your own conception of a self? Or perhaps I bored you, my eccentricity only amusing for so long, its value now exhausted in your unconvinced mind. Were you always too altered, too consumed by chemicals or reckless desire, to care what remained of me in the morning? But why call a thing incredible, when you no longer want it at all? Your intentions were never decipherable, never spoken. Was I simply not useful anymore?

“You’re a special person, Grace Tully.” Those were the last words you spoke in the first hours of knowing me, on that beautiful and perhaps regrettable night when I first let you make love to me, and began to understand that I was not yet ruined or damaged beyond repair, and that there was something left for me to strive towards. I have remembered those words ever since. Maybe they were true. Maybe you believed them. After all, I was so alive and extraordinary and strange back then, with my shining eyes and my half-starved frame, irradiated by the incandescent recollection of my better days. But I have been fighting for my sanity for a long time now. How can you be horrified to see that I am losing? Of course I am not the person you used to know: that person faded with the early winter, she choked on every plea for help that went unanswered. So do not be too critical, or unsettled, or confused, by whatever it is that I have become. This change was not a thing that I could have prevented on my own, and although I tried and tried and tried, no one was willing to aid me.

I will find another figure now, and learn to love it all the same, until this matters less than a memory. If you have not already, then you must forgive me–but I doubt that will be necessary. I have been given little cause to believe that this absence-riddled grief is known to anyone but myself, and I truly do hope that I alone should feel it, if that is the choice we both made. I always fall a little in love with the things that I am soon to lose, and this was never going to last. I knew that, we both did. It never unsettled me. I just did not expect the end to come in so thoughtless a form.

But you saved my body. Of course that mattered. Try though I might–and mark me, I have tried–I could not make that meaningless, not ever. I just wanted one thing, one stupid, useless fucking thing: I wanted you not to hurt me. It is not complicated. I cared for you. I thought you understood that. I might wonder, sincerely, whether I had asked too much of you. But even now, I will not debase myself in that way. I have to know my own value. I have to know that I am worthy of the tenderness that I strive consciously to offer, and so expect in return. I have never pined for anything that I was not also willing to give. I have to believe that counts for something. So I will take this, all of this, everything that was done to me, all of the people who left me alone, who made me ashamed, who watched me cower. I will wear this upon my failing body like an albatross–and then with chemicals or electric currents, I will burn it out of me. I will purge my mind of its own inclinations, and make myself clean again.

But I will leave claw marks in the flesh of these unforgettable days. I still recall when they began, and what that felt like, and how much I learned and grew and healed. I know that this meant something to me. I am not sure, in fact, when or how it came to matter so entirely: the change was rapid and sentimental and scared me. I am still so afraid to feel this way, and I cannot pretend that you have not given me cause. I am not in love, I am never in love, I am too far gone for loving–but still I adore you, and I will miss you, and I am sorry. I want to remember something better than this. I want there to still be a chance. I will want that until the very last. But I have so little desire left to spend.

Someday I will write this all, and honestly. I do not regret it, not entirely, not yet. But I need the space to hurt now. I believe that there is very little left for me to do. I am not sure whether or not you feel this way as well. I worry that, mostly, we need time, and there is no time left for either of us now–because I am going home, and when I come back, I might not be the same. I think that our days are ending. I am afraid that you might have wanted them to. I do not know how to feel about that, or how to survive it. But these things are always temporary. No one knows the same love twice. Nothing ever really lasts. So I think that our days are ending–and that maybe it is time for me to stop writing, and let them.

“…Only

we can regret

the perishing of the

burned place.

Only we could call it a

wound.”Margaret Atwood, A Fire Place

I am going under the knife again.

I have often doubted whether, for anyone, such an endeavor could be necessary twice. But I think that this mind of mine may be dying now, undone by the discordant anxieties that roar through my body and split the searing soul.

I poured currents of salt water and measurable time between myself and my lived existence: the history that consumed my physical form, the paranoia and the people that broke me. I tried to purge myself, to burn from my skin the trauma of those who abandoned me, who rejected me by not being there, who left me impaled upon their absence. All of the empty promises, all of those beautiful lies: no one protected me this time, and so I protected myself. But no body can sustain its own worth indefinitely, whether it is driven by anger or by some horrible love. I have become emaciated, my flesh a grisly pattern of bruises, scabs, and scars. How the hell could I have allowed this to happen? I am afraid to leave my room in the mornings. I hardly even know my own name. And fuck you, fuck all of you, for loving what you thought you understood and failing to take care of it anyways. Fuck you for letting me adore you and then disappearing again. Fuck you for making me feel dispensable. You saved my life and you shattered my mind and you made me wish that I had been left alone from the start. This is your indictment, as much as it is mine. At long last, I am writing for us all.

At any rate, I cannot survive another year of this. So I am going back to my own beginnings, to those sterile rooms wherein shame and isolation drip like morphine through my blistering veins. Yes, I am afraid. But this time I will give myself up willingly. They can have everything, they can have my name, my clothes, my history, my body–for I have no health, and I want health desperately. I want to be new and whole again, I want to be better for the people who still trust me. So take it, please, take it all. Get this thing away from me, this flesh, this madness, this consciousness colder than surgical steel. I do not want it, not any of it, I never did. But I was not given a choice.

I sometimes fear that I am not a thing worth keeping alive. You liked me so much better before learning what I am. I opened my eyes this morning and you were already gone. I was surprised that I could still feel anything by then, but I woke up alone and I wished that you had stayed. Or maybe I just wished that I was worth staying for. But I will not crawl, not ever, and so when I stood at the world’s edge, upon that rooftop, I climbed higher than I ever have before. The morning light was cold. My arms were outstretched. My feet were on the brink of some limitless oblivion, some ineffable liberation, some chaos like surrender and some tragedy that might set me free. I understood, at last, that Icarus could never have been consumed in flames without suffering, eventually, his invaluable descent. But might it have been worth the fall, to burn so unforgettably? Some part of me wanted to learn this for myself. But instead, I stepped back from that compelling precipice. I called my mother, who sacrificed her body to bring me into this beautiful, terrible world. I told her at last, in my own way, how very much I love her. Then I covered my ancient wounds in something new.

So many people fear their own fragmentation. But I was undone in the beginning. I have no interest in pretending that I am anything other than mercurial, impassioned, half-insane. This story was written long before I knew what form it would take. Tiresian in nature, my language has predicted it all–her empty womb, that false crucifixion, the genderless prophecies, the horror of my own burning. Maybe this was the inexorable trajectory of my existence. But even so, I have to be better than this. I love him, her, them, you: I used to love myself, but I cannot love what I have become. This is not me, it is not, I refuse to accept it, I am not like this and I never was–not this broken, not this wasted, not a site for senseless suffering. Please, please, forgive me for this, for making it all so inescapable. Give me time, and nothing more. I will be whole again. I will be better. It will not always hurt so much.

Subject me once more to the scalpel, and cut it all away. Sedate, anesthetize, lobotomize me–do anything you like, so long as I am well again. I want to pull my own skin apart. I want to tear it back and I want you to dismember me and I want to feel no pain. I will not have any more of this: the sleepless nights, the horrors in my periphery, the bouts of paranoia that make a nightmare of us all. I cannot endure many more days like this one, exposed to the sunlight, eyes downcast, consumed with some wrenching fear that I am alone and relentlessly despised within the confines of this rough reality. Nothing ever really helps, for I was not made to be saved. But I do not want your concern or your sanctimony. I just want to write. I want to heal. I want to not feel scared. I want someone to love me the way my dad never could.

How lucky I am to be alive in this miserable world. I think that it was always coming to this. It is difficult to feel anything but fear, but I have been steadfast in my endurance for a long time now. Surely, I can keep on for just a little while longer. Thank you for surviving me–thank you all. There seems to be nothing left within me that can justify this, that can make it feel meaningful, that can put me back together again. I have tried and I have tried and I have tried and I have tried, and this is all that it amounts to. But even now, I want to be well again. I know that I will continue on. No one should have to live like this, and maybe that place can set me free. What, after all, have I left to lose?

I miss you, I love you, I hate you, I am you, and so I endure us as one. Return to me, please, and be whatever it was that you used to be. I would give anything to have you back again. So forgive me. Please. I love you. Please. You could never have made me whole, but it means the world to me that you tried.

I am going under the knife again. What more is there to say?

You hold an absence

at your center

as if it were a life.Richard Brostoff, Grief

I should have known, I should have known, that even a nightmare ends. Things are still so difficult, but getting better now. I wonder if you will notice. I wonder if you will care. I hope that, someday, you read this and realize that I remember it all. I hope that you have not yet lost faith in my endurance. I hope that you know how brilliantly, unbearably alive I still am.

In the last act of our horror-show scene, what I saw nearly undid me: his skin, this skin that was not mine, had split beneath my fingers like a scream– the image runs even now like a needle through my mind. A baby’s breath or a barren womb could hardly have warranted that. But what a misery it seemed: he was impaled upon a loss that could not be. His grief was all stitched with the absence of a life that never was, and I could not put the body back together again. So I found myself half-anguished, later in the night, smoking and speaking aimlessly to her sleeping form. I am lost, I said, in my etherized state: I am lost and I am trying to find my way back to you. But she could not hear the madness or the music in my mind, and when I did what I thought I had to, it hurt beyond all imagining. I melted and seared, and layers of me fell away with the smoke.

Had I not always said that I wanted to burn? Did I know what it entailed? Have I always known? Maybe it was always coming to this. There was nothing left to expose to that flame but me. And what was I then–Icarus, now fallen? Electra, already consumed? The sacrificial compensation for some ancient, nameless sin? Or was I was only myself, a self that I had hurt, and if so, could I ever recover? When all of it was over, I was utterly devoid of thought, with no force and no fire to speak of. I was fifteen again. I was ashamed. I was an open space, a darkness aching to be made into something new.

I needed him more than ever then, the one who gave form to my solitary endeavors, whose loss I feel only in the half-light of morning, and in the deafening silence of that forsaken room where I used to feel beautiful when he moved in me. But I am tired now, and so undone: I can scarcely recall the hands that pressed against me, and kindled some dim fondness in my bare, still-beating heart. My face between those steady palms, each subtle, half-conscious movement of his form, the gentle hesitance that lent me the strength to continue–my body was a thing we learned as one. And in the moments when it turned upon me, and I recoiled with the soreness of a long-festering fear, he stayed beside me anyways. Even a mind as guarded as my own will know, one day, the wound of his absence: perhaps so profoundly that I will wish he had never found me at all. Beautiful things must always, ineffably, be mourned. His were not the hands that brought me the joy of some impossible desire: he was not the figure for whom I knelt beneath the surface of that foreign shoreline, and felt wonderful and helpless and alive. But he was the clandestine surface whereupon I grew less afraid, and whatever I am becoming now is stronger, mending, and imbued with some quiet gratitude. Those months were sacred: there will always be love there.

What have I come to since the summer? There is no way of telling, not anymore, and maybe there never was. All I know for certain is that it has been a long year. I can say it until I run out of breath, but it is true, it has been so long, and how I have lived since I roamed the streets of New York City in wonder and grief. I now know, less than ever, where I am, where I may go. My father, my family, the girl I thought I could love: did I leave them all behind? Or were they lost before I crossed that sprawling sea? Her voice like raw silk, and all of the rough choices she made: for the first time in so many long and terrible months, I found her, really found her, once more. Those intonations reminded me, if only for an instant, of who I used to be, and all of the ways I used to feel. I met again the woman of these nine months past, whose specter lingers in each new bout of melancholy. “Always” was a handful unforgettable moments. “Always” was an ending that nearly broke me. “Always” was a promise we were both too young to keep.

Always. Always. That word belongs to her now, but its consequences are my own.

So when he wandered through my bedroom door, with the carelessness and integrity I had tried so desperately to forget, I reacted without meaning to, though I could never have anticipated the words that fell hesitantly from his mouth. I knew, with such damning sincerity, precisely that which I had been afraid to know: the feeling of having felt, of having loved and forgotten. It had been so long since my mind was one with his. Some half-recalled adoration stirred in my guarded form: the final evocations of the child who adored him, who still hoped that maybe his gentle consciousness could repair itself, that maybe late autumn was just a ruse or a terrible dream. That secret part of me ached to silence each lingering doubt, abandon entirely my better judgement, and try to love him one more time. But it cannot be about that. It will not be about that. I have no innocence left to give: and even if I wanted to, I could not endure our history twice.

I really think I like you. I like you, I like you, and your disbelief cannot cure me. I can only hope that you never begin to understand. In the horror of my last dissociation, I was sitting in the front quad, and I thought that I could see straight into the core of each ancient structure in my periphery. The frameworks were skeletal, all of their grandeur gone–I realized that a house of God, when not alight with song, is a hollow thing to witness. That day I saw through dreaming spires, and into the heart of some harsh and corrupt reality: the bare bones of a world where strangers and children play unforgivable games, and where I learned to trust no one but myself. This city has been killing me slowly, and for longer than I have cared to admit. But it does not always have to feel this way: and even now, I am not sorry. Not for what was done to me. Not for what I am.

My healing, my salvation, will be made possible by the very things that brought me here to begin with: the half-mad fears and longings that first reduced me to this state. For all of the reasons that I suffer, I will also, inevitably, survive. I am certain that I sound histrionic, and perhaps self congratulatory, once more. But that does not matter: it cannot matter. These are the things I tell myself because I have nothing else to say, and because I see no better means by which I may endure or engage. The dream of a normal death, a natural death, a death not inflicted by the hands that write this piece, has not always been more than mere fantasy for me. I have clung to it in desperation and desire when it seemed less likely than a miracle. If I was not ready for this life, it was only because I did not believe it was possible.

Someday I will write, in full, the history of this form: in gradients of desire and each forgotten cross I have climbed. I will give a language, at last, to whatever absence breathes and burns within me, to the specter of my wordless story, and to the child who I cannot mourn, having never learned her name. I do not know where it is taking me, this body that atones. I know that I am not well yet. To heal will require time, and even now, I feel listless and wary and disillusioned as all hell. Survival is the art of accepting nothing more or less than your own continued existence–and so I have always lived like this, because I knew no other way.

But I have done my penance, for now. I have taken measures that unsettled even me, and I have given months of my life to the people I am striving to love. So let it be over now, if only for a while. Tell me that I have suffered enough, and let me lay these ghosts to rest. I have always been peculiar and half-aimless and inane. I am disparate and I am flawed beyond measure. I am beautiful and strange. I am the blistering core of your discontent. I am the center that holds. But more than any of that, I am older now. I am stronger, I hope. I am finally ready to try again.

What will I become, now that I am no longer content to merely survive?

‘We never look at just one thing; we are always looking at the relation between things and ourselves’

– John Berger

How do forms of literary description ask us to look at ‘things’ AND/OR at the relations between the self and the other?

In much of the literature and history of the English canon, the corresponding notions of ‘self’ and ‘other’ have denoted, in conjunction, one relatively simple paradigm of oppositional identification, wherein the ‘self’ remains broadly separate from the ‘other’ (or entity of comparison). But developments in feminist, postcolonial, and Marxist literary thought complicate this phenomenological schema by foregrounding the racially ‘othered’ self, and specifically, the Black self. Edward Said, Franz Fanon, and Jean-Paul Sartre all address, to varying extents, the manner in which a realized Black identity can function as both ‘self’ and ‘other’ simultaneously, due to its historical and ongoing positioning within the racialized structure of the West—for while a Black man might identify a white man as ‘other’ in relation to himself, the pre-existing systems of power in the West mandate that this white man be perceived as “not only ‘the Other,’ but also the master” (Fanon, 148). From a hegemonic standpoint, then, it will always be the Black man who is ‘othered’: his relentless marginalization is ensured by the very nature of the structures already in place. This dynamic ascribes a relative lack of demarcation to the Black identity, within the given phenomenological model of ‘self’ and ‘other,’ and thereby necessitates a category of critical theory that interrogates the interaction of oppositional identification beyond these binary foundations—that is to say, a discourse that addresses not only the ‘self’ and the ‘other,’ but also the ‘othered self.’

Toni Morrison’s 1987 novel, Beloved, epitomizes the strategies and ideals of such a discourse; as early as the first pages of the text, Morrison’s depiction of the fraught relationship that the protagonist, Sethe, endures with her own ‘self’ fundamentally disallows for any diametric reading. Of course, as a Black woman in antebellum America, Sethe is perpetually ‘othered’ in relation to the conditions of her existence; the parameters of her selfhood are thus defined, at least in part, by their oppositional positioning against the literary backdrop of a patriarchal, white supremacist culture. But even beyond the sociopolitical assessment that Fanon emphasizes, the character of Sethe demonstrates a number of compelling tensions between various forms of oppositional identification. The body upon which the narrative takes form, and wherein Sethe’s conflictions and identity are rooted, is maternal as well as formerly enslaved; therefore, its associations to motherhood recall many of the differential paradigms of ‘self’ and ‘other’—specifically those pertaining to children, such as Lacan’s mirror phase or the psychosis of the nursing child. Throughout the narrative, Morrison draws upon the notions of oppositional identification that her thematic emphasis on maternity has produced, employing the selfsame images of birth and psychosis to represent the horrors of slavery. In this fashion, Morrison brilliantly depicts a loss of differentiation between mother and child that mimics the absence of demarcation associated with enslavement; the maternal and formerly enslaved body of Sethe thereby provides the vital symbolic link between each instance of differential identification of the ‘self’ that the text contains.

It is precisely this nuanced representation of the Black ‘self’—as a kind of self-actualized, cultural ‘Other’—that facilitates Morrison’s narrative recalibration of racial centrality in Beloved: what Beth McCoy identifies as an “authorial shift from racialized ‘object’ to racialized ‘subject’” (McCoy, 44). The narrative of Beloved provides, through the production of the text itself, a literary realm wherein the Black ‘self’ is no longer reduced, like some bizarre form of racial chiaroscuro, to an othered foil for the white ‘self.’ Instead, the juxtaposition of a Black ‘self’ against the white ‘other’ establishes the conditions upon which the thematic weight of the novel is largely contingent, by allowing for a differential formation of the Black ‘self.” But this is not to suggest that the full relevance of Black identity in Beloved should be reduced to its terms of relation to the white supremacist paradigms that preceded it; on the contrary, to do so would resituate Blackness as oppositional to the Eurocentric presuppositions of the canon, and thereby reestablish whiteness as the “objective” center of criticism. Nevertheless, the fraught interaction between Morrison’s literature and the aesthetic conventions of the medium with which she engages lends her work a heightened sense of sociopolitical subversion; it therefore seems tantamount, in critical analyses of Beloved, to approach its conceptualization of Black selfhood both in relation to the white supremacist paradigms that inform the text, and as an organic discourse in its own right. For while Morrison’s text reckons fully and consciously with the pre-existing myths of white centrality, the novel is in no sense dependent upon them; on the contrary, Morrison articulates throughout Beloved, “a fully developed theory…that is central to her larger political and philosophical stance on black identity” (O’Reilly, 1).

In any relation between a ‘self’ and ‘other’ within the initial phenomenological model, there is necessarily a degree of oppositional distance whereby the identity of one can be induced from its relation to the other. But the events that inform Beloved’s narrative core are defined by the near-total absence of this distance; instead, the text is linguistically, syntactically, and thematically characterized by an almost staggering sense of intimacy. This loss of differentiation, which the Black ‘self’ suffers both in a phenomenological sense and in the circumstances of the narrative, is disturbing; thematically and linguistically, Morrison draws the Black subject within the narrative into the proximity of the white ‘other’ and makes any form of distinction almost unsettlingly difficult. The most memorable instance of this occurs, of course, when Sethe sees her former masters approaching her home, and reacts against the violence she anticipates by murdering her own daughter. In this instance, rather than replicating the traditional model wherein the ‘self’ and the ‘other’ establish a sort of necessary contingence upon mutual opposition, Morrison depicts a reimagined sense of identification that seems, rather than differential, disturbingly similar. The distance between ‘self’ and the ‘other’ is thereby eradicated; the two become not foils, but mimetic horrors of one another and themselves. This hideous sense of like identification can be read as an allusion to the disturbing mutual reliance of the slave and master upon one another: a specter of the Hegelian master-slave dialectic that haunts the foundations of the text.

But the physical images of intimacy and proximity in Beloved are certainly not limited to the racialized conceptions of ‘self’ and ‘other.’ In this same scene, Morrison also uses near-identical imagery to represent the problematized sense of differentiation inherent between infants and the maternal figures who have been, as historian Walter Johnson articulates, “…forced by their slavery into a doubled relation with their bodies and their children” (Johnson, 11). Even before the supernatural return of her child, Sethe enfolds her daughters within her own maternal identity: in the moments leading up to Sethe’s grisly murder of her own daughter, Morrison writes, “…she collected every bit of her life she had made, all the parts of her that were precious and fine and beautiful, and carried, pushed, dragged them through the veil out, away, over there where no one could hurt them…where they would be safe” (Morrison, 163). In this passage, Sethe’s children are described as “parts of her,” engulfed within the greater whole of the maternal body. In some sense, this image could function as a poignant indicator of Sethe’s limitless devotion to her children; but this reading is problematized by the sheer brutality of Sethe’s subsequent actions. Instead, the overlapping of Sethe’s identity with that of the murdered child seems to thrust the ethical nature of her infanticide into ambiguity, suggesting that she has killed a “part of her,” rather than an autonomous human being. The very language of the passage obscures the agency of the murdered child, thereby casting doubt upon whether Sethe’s actions were a ritual sacrifice, or a kind of suicide. In accordance with this image, the allegorical distance between Sethe and Beloved becomes virtually nonexistent in the text: Jean Wyatt argues that Beloved’s fixation on Sethe echoes infantile psychosis, mimicking a “desire to regain the material closeness of a nursing baby” (Wyatt, 474). This insight is augmented by the images of blood and milk that imbue the narrative recounting of Sethe’s “rough choice” (Morrison, 180), and Morrison’s frequent use of terms like “hunger” to associate Beloved’s desire for Sethe with a desire or need for consumption. Similarly, the sense of utter unification that Sethe experiences is shared by Beloved, as indicated in the ambiguous line, “You are my face; you are me” (Morrison, 216). This quotation appears in arguably the most haunting and obscure section of the text, wherein Beloved’s further references to being “in the water” (Morrison, 216) also function as a potential description of the experience of a child still in psychosis: completely void of identity, and utterly unable to differentiate any semblance of identity separate from the body of the mother.

But at various points in the novel, Beloved also seems to carry within her the entire history of American slavery; in light of this, the appalling conditions, overwhelming darkness, and horrific proximity of bodies that she describes can also easily be read as a description of a voyage on an American slave ship. The very language of the passage is spatially devoid: punctuation is lacking and words seem to merge upon the page, signifying a disorienting and overwhelming sense of physical closeness that represents, according to Wyatt, “The loss of demarcation and differentiation of those caught in an ‘oceanic’ space between cultural identities, between Africa and an unknown destination” (Wyatt, 474). In either reading of this passage, this proximity is defined as a categorically dangerous state of being—a conviction mirrored earlier in the text by the grisly nature of the master- slave dialectic, and later by horrific consequences of Sethe’s lack of differentiation from her daughter. “There are no gaps in Sethe’s world,” Wyatt writes, “no absences to be filled with signifiers; everything is there, an oppressive plentitude” (Wyatt, 474). The complete lack of any form of distance between the Sethe and Beloved, whether it is read as the extended psychosis of a nursing child or a supernatural manifestation of the horror of non-differentiation within the Middle Passage, impedes Sethe’s conception of herself and very nearly consumes her.

The tragedy inherent within Morrison’s multifold, symbolic use of motherhood throughout the novel, particularly in relation to Sethe’s volatile relationship to her maternal and once-enslaved body, is particularly evident in the manner in which the various pieces of textual imagery simultaneously inform and corrupt one another in seemingly arbitrary, incongruous, or even upsetting ways. Slave masters, schoolteachers, mother’s milk, rusted shackles, childbirth, pregnancies, blood, slave ships, steel bits, frightened mothers, laughing children, empty homes—as the images clash and conflate, their horror lies, unsurprisingly, in a lack of differentiation. In this sense, the entire text allegorizes, through a number of narrative, linguistic, and thematic mediums, the white Other’s hegemonic perversions of the Black effort to formulate a realized self within pre-existing phenomenological terms. Although she offers no categorical solution to the problems of differentiation and identification that the text so thoroughly interrogates, Morrison nevertheless provides her audience solace in the form of the novel itself: a riveting narrative plane wherein the realized Black ‘self,’ though relentlessly ‘othered’, can nevertheless be represented and identified on its own terms—and where the Black maternal body, despite its history of suffering and enslavement, can provide this still-emerging ‘self’ with an intimate physical site of violence, desire, and resistance.

Works Cited

Collins, Patricia Hill. “The Meaning of Motherhood in Black Culture and Black Mother/Daughter Relationships.” Sage: A Scholarly Journal on Black Women 4.2 (1987): 4-11. JSTOR. Web.

Fanon, Frantz. Black Skin, White Masks. London: Pluto, 1986. Print.

Ghasemi, Parvin, and Rasool Hajizadeh. “Demystifying the Myth of Motherhood: Toni Morrison’s Revision of African-American Mother Stereotypes.” International Journal of Social Science and Humanity IJSSH (2013): 477-79. JSTOR. Web.

Hirsch, Marianne. The Mother/Daughter Plot: Narrative, Psychoanalysis, Feminism. Bloomington: Indiana UP, 1989. Google Scholar. Web.

Johnson, Walter. Soul by Soul: Life inside the Antebellum Slave Market. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 1999. Print.

Morrison, Toni. Beloved: A Novel. New York, NY: New American Library, 1988. Print.

O’Reilly, Andrea. Toni Morrison and Motherhood: A Politics of the Heart. Albany: State U of New York, 2004. Print.

Wyatt, Jean. “Giving Body to the Word: The Maternal Symbolic in Toni Morrison’s Beloved.” PMLA 108.3 (1993): 474-88. JSTOR. Web.

© 2025 Forms of Boredom Advertised as Poetry

Theme by Anders Noren — Up ↑

Recent Comments