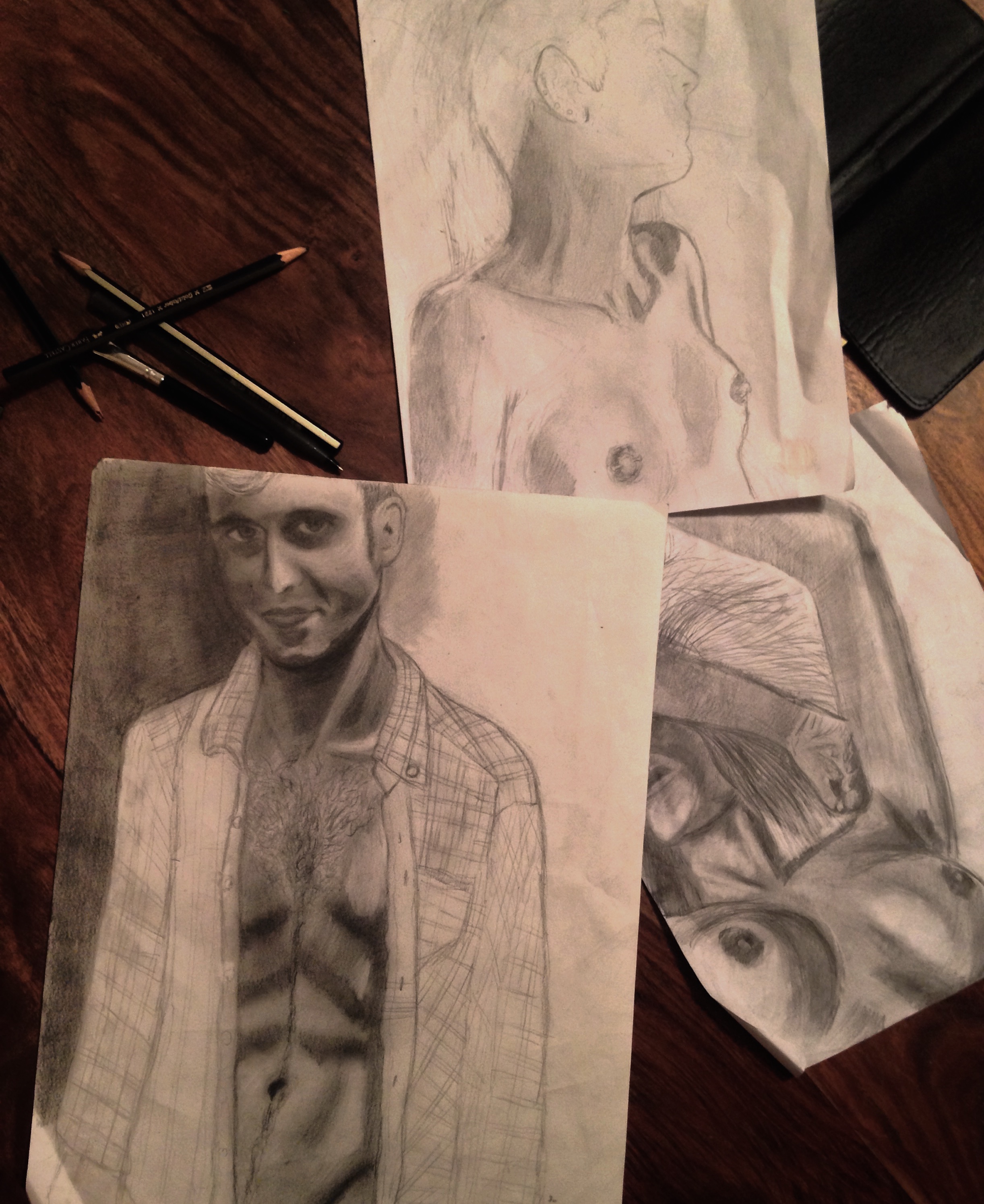

charcoal and #2 pencil. january 3, 2016. (unfinished).

just an update on a few of the pieces I have been working on

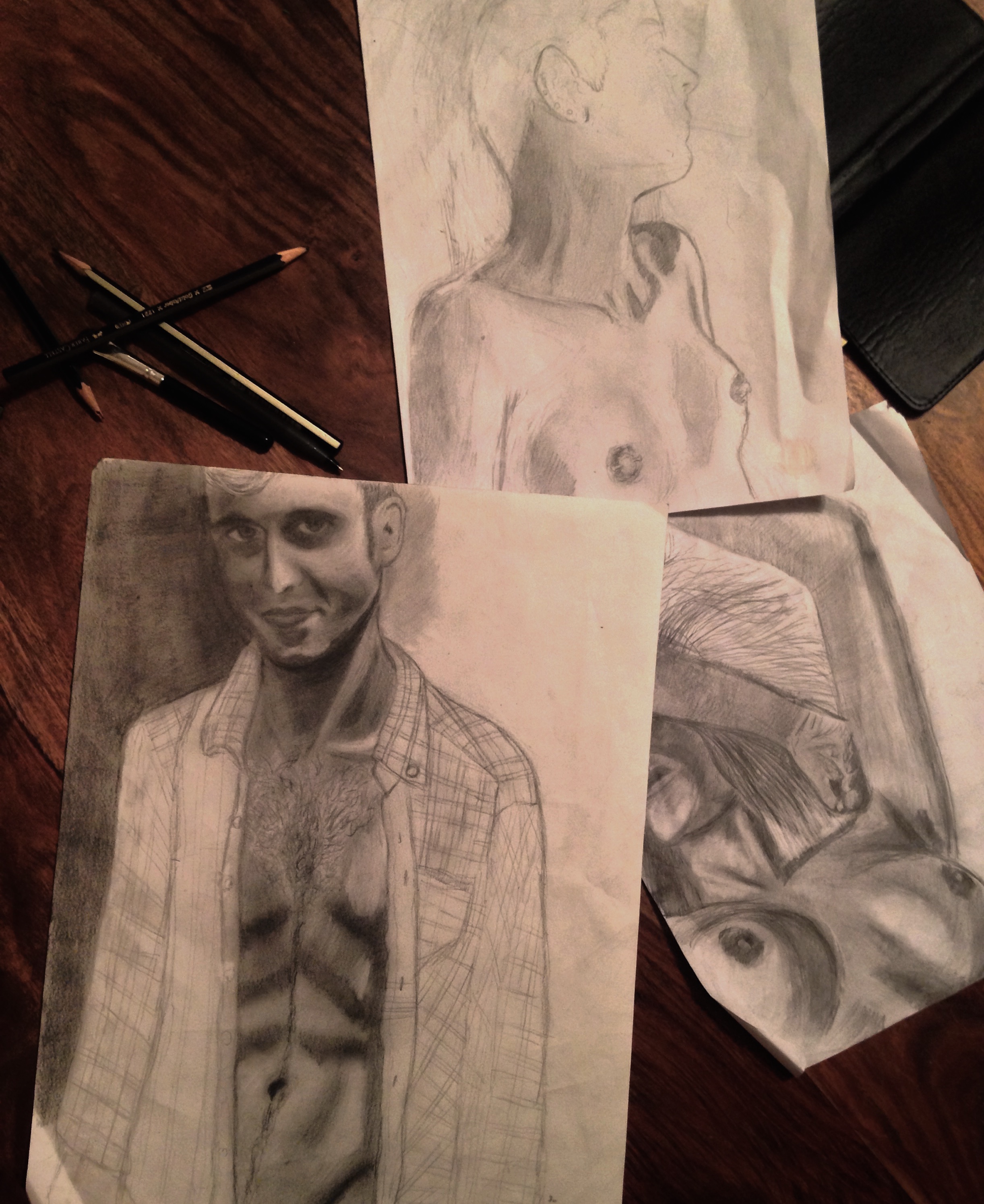

charcoal and #2 pencil. january 3, 2016. (unfinished).

just an update on a few of the pieces I have been working on

For my mother, who knows who she is.

Alison Bechdel, Are You My Mother?

I recently had the pleasure of working with Corinne Singer and Maggie Kobelski on Corinne’s ongoing series in feminist self-portraiture. The first installment, entitled “Mother, May I?,” came into being in late December when, at the seaside town where I once spent my childhood summers, I walked into the Atlantic Ocean wearing my mother’s wedding gown.

For as long as I can remember, it has simply been expected that I would marry in that dress; but following the deterioration of my parents’ relationship, my struggles with mental illness, and my efforts to come to terms with my own sexual and gender identity, the oppressive implications of such an assumption took on violent significance. Always symbolic of conformity, by the time of the shoot my mother’s wedding dress had become a representative site upon which the traumas of my adolescence—the toxic constraints of heteronormativity, the lingering anxiety of disappointing my mother through my unconventional state of being—were made manifest.

In some ways, “Mother, May I?” functions as a visual counterpart to “Love and Other Theories of Subjugation,” wherein I describe an allegorical scene of submission in (and to) the waters of the Atlantic, reflecting upon my own psychological need for respite. In other ways, it was a challenge to my own body: kneeling in ivory satin among frigid water was a means through which I could explore my own physical limitations, and in doing so, engage in an incomplete (but perhaps not entirely futile) effort towards transcendence. In the latter regard, the entire endeavor can potentially be read as a reflexive, even masochistic act; more than anything, though, it was the visual extension of my understanding of the human body as an intimate site of desire and revolution.

The conceptualization of this piece drew heavily upon the feminist tenants of physical reclamation. My status as a neurodivergent, differently abled queer person with a complex identity that includes ‘woman’ is visually and thematically evoked in the lines of Sapphic poetry painted onto my body: the characters along my collarbone read, “Someone, I say, will remember us, in another time,” while “Hymn to Aphrodite” extends across my back and shoulders.

Efforts at self-portraiture are complicated by the many facets of my identity that cannot be reconciled. With regards to the trajectory of the photographic narrative, however, the themes that come immediately to mind are captivity and sacrifice, abandonment and solitude, violence and desire, sensuality and subjugation, shame and self-medication, resistance and liberation, baptism and rebirth. In my artwork and my writing, I have rarely achieved the sense of catharsis that I experienced when modeling for this piece.

This narrative is dedicated to my parents, my queerness, my body, my resistance. It is dedicated, in short, to the willful destruction of beautiful things.

1. Surrounded by containers of makeup, clad from the waist down in my mother’s white dress, I face a mirror imbued with my form. Although it was originally intended as a test shot, I begin to view this photograph, the first in the series, with uncertainty, and then fascination. It is transfixing to gaze upon my own image, twice framed: so strange to see myself unintentionally misrepresented as a lovely and feminine thing. Sunlight filters through the windowpanes, soft against bare skin: gradients of shadow, beautiful and subtle, adorn the folds of fabric. In this effort towards self-portraiture, I am the object of my own contemplation: the project begins, as it likely should, with the ongoing question of my gender, and a conscious performance of the self.

2. Kneeling in the sand for our carefully constructed evocations of traditional wedding photographs, the first thing I am conscious of is being colder than I could have imagined. The diaphanous fabric of the veil is cast away from my face, revealing an incongruous joining of propriety and discomposure. The dress, which encompassed my mother’s form so gracefully when she was only 25, is too large for me: reams of white satin drape awkwardly over an angular frame emaciated from cigarettes, sleepless nights, and too many other mediums of self-consumption. Tendrils of dark hair are not quite enough to cover the shaved and tattooed side of my head. My eyes are shadowed, deep-set; my skin is scarred and pale; my lips are ashen, almost anemic; my countenance echoes the muted tones of the landscape surrounding me.

3. These are the photographs that my mother dreamed of someday seeing when she gave birth to me, her only daughter. But like the dress itself, they do not fit: they are unsettling, dissonant. Discontent textures each image: the specter of a captivity that has haunted me since childhood, informing my longings and impeding all efforts towards resistance. I emanate a stark sense of discomfort with the parameters of my sociocultural existence; is this is the only permissible way for my body to fill the space around it, as the object of another’s gaze?

4. I cannot be adequately represented, or even contained, by those sterile, bloodless images of a woman that I am not. So as the daylight begins to fade, we focus increasingly upon the boundaries associated with gendered and sexual conventions, and the instability of desire that such margins ascribe. The tide advances: I move towards it. The veil is disposed of; the shaved hair, the many piercings, and the dark ink become visible along my skin. No further effort is made to keep the dress from slipping off of my tensed shoulders as I crouch like an animal, anointing my face with water and marring it with sand. Makeup runs in dark rivulets, and my hands clench and claw at the earth, craving a nameless liberty. I am abject and full of rage. Rage for my mother’s abandonment, rage for my own psychological mutilation, rage for those years of self-loathing that gnawed away at my sanity until they made me what I am. My entire body reacts against the fact that I was given so little say in what I would be expected to suffer and survive as a woman, as queer, as fatherless, as alive.

5. These recollections inspire a natural, almost involuntary defiance: inspired by Yoko Ono’s “Cut Piece” and its connotations of sociosexuaul violence, we tear away at the fabric of the dress, mangling gossamer sleeves, exposing bare skin, smearing wet sand across the intricate lace bodice. These willful acts of destruction constitute, for me, a rejection of the imposed existence that I accepted for too long; but no act of violence towards my half-remembered history can alleviate the isolation of the present. A vast expanse of water, smoother than glass, serves as yet another mirror in which to survey my own solitude: nowhere is it clearer how damningly alone I am, even as the subject of my own narrative.

6. My reflexive response to the most isolating moment of the shoot is the immediate assumption of a more sensual pose: within misremembered paradigms of sexuality and subjugation, I seek solace from “my grief and maddening solitude.” The impulsive motion is simultaneously masochistic and liberating—what better respite from the brutal senselessness of this existence, than a reckless and ongoing engagement with the selfsame acts of desire and decision that every known standard of gendered propriety has attempted to exert from my still-breathing form? Skin exposed, body rigid with the cold, I kneel in the shallow waters, gripping my heels with my hands…

7. … and then wrap my arms about myself defensively. Desire followed by vulnerability, longings complicated by half-realized fears, there is something almost fragile in how thin I appear, enshrouded in the dissembled silk that floods around me in tides of white.

8. Something close to beauty, utterly strange and distinctly sorrowful, emerges from these positions of imprecise susceptibility. Kneeling upright among the currents, I evoke, almost unconsciously, a sort of seraphic imagery: “aurochs and angels, the secret of durable pigments…the refuge of art,” in the words that Nabokov wrote, which imbued me with melancholy so many times over, leaving their impressions in the contours of my memory and soul. My posturing is both natural and dimly mythological: recalling violence and self-preservation.

9. Fingers numbed, it is nearly impossible to light a cigarette—but I know that if anyone can do it, I can. The act itself illuminates my bizarre, precarious relationship to smoking and social shame: the stigmatized practice of self-medication that has come to inform, and even characterize, my identity in so many relevant ways.

10. In my dissonant conflicts with “this slowly dying body,” smoking is a habit I engage in because it allows me to remain as sane as I am capable of feeling; it is an addiction born of trauma, which has nevertheless become entirely my own. I can claim each breath I draw, and feel no shame for the choices I have made, even as they consume me. There is, after all, a certain absurdity to the thought of a world that has nearly killed me in so many different ways, chastising me for something so inconsequential. For me, for now, smoking is an act of strength and resistance: it is a reaction to the culture that reprimands self-medication without paying mind to its origins or the consequences of its absence. After all of the ways in which I have been damaged or undone, this, at last, is an action I can inflict upon myself.

11. By the time the cigarette has consumed itself, burning away into ash, I evoke a very different image from the subdued girl with the fading roses and downcast eyes. Intrepid and irreverent, my resistance has carved a space for my androgyny, my sexuality, my multifold and semi-performative identity. The dress has been destroyed beyond repair, leaving no means of going back, of mending whatever damage has been done to that beautiful white fabric. I have torn it from my own body, and am occupying my surroundings now as more than an object of desire or aestheticism. I am too cold to feel my own skin, but the rhythm of my pulse is more realized than ever. My eyes are burning, framed in black; my hair is disheveled; the protective lines of Sapphic language have washed away, leaving only my bare skin and its many strange desires. There is a primitive, almost feral element to my defiance.

12. Despite all of my frustration and retroactive grief, it is a mournful and lovely thing, to lay waste to the dress my mother thought to see me married in. The gown is still beautiful, even in its ruined state, as I kneel beneath the luster of these radiant skies. It feels like a baptism, to immerse wholly in the currents, to reckon unflinchingly with the girl I was, the person I am, whatever I have yet to become. In some wonderful sense, it is the inimitable extension of that longing I have expressed so many times before, to leave “my life and my name and my consciousness in the keeping of those waters… to know that there is someplace left to lose myself.” Is this what it feels like to finally begin to heal?

13. Maybe—but then again, maybe not. After all, despite whatever language and meaning I impose upon it, the story the fabric tells is simple. I need a new beginning. I think I always will. So on the shorelines of my childhood, and in the object of my eternal fascination, the sea, I try for the next best thing.

14. Amid those timeless waters, I evoke the sensation of being reborn.

We have to consciously study how to be tender with each other until it becomes a habit.

Audre Lorde, Sister Outsider

Every time I bleed myself out in front of a blank page or a computer screen, I am reminded that it is damn near impossible to communicate fully, to forge the connections and the intimacy that I crave, when writing so directly and consistently about myself. But I continue to do so, for now at least, because for all of my confusion and my restlessness, I am something that I know. There are worse things to write about than that, I suppose.

Ghosts of my past reemerge with the dawning year. There are bones that I never put to rest, and people I could not keep alive; yes, that beautiful girl died, with white roses in her hair and eyes, but it was not entirely a tragedy. People change, after all, and what of it? If you do not know what I am writing about now, it is because you were never intended to understand. But for the briefest instant in our burning worlds, she was mine, and I was hers. That will always be true, it could never be anything else. What more can I really care to know?

How long do resolutions last? I am impractical, but not entirely naïve. I understand that a turned page in a marked calendar bears no real significance. I have never had the constancy or the resolve to keep the commitments I devise; but I will make my promises, all the same.

In 2016, I will remember, always, the treachery of pleasure: the unspoken wariness of anyone whose love, for as long as they can remember, has been mingled with trauma and directionless sorrow. I will remember that I am a body in need of protection, and that this is a beautiful thing. I will remember to stop projecting my fierce and nameless needs onto sites of imposition, be they desirous figures or gentle minds. I will remember to find secret, tender parts of myself and keep them very safe: to give less love where it is not wanted, and so carve out a space for myself in the world.

In 2016, I will find more spheres of women, queers, and people with complex identities that may include “woman.” These communities love deeply. I want and need to be cared for in that way. I will touch and be touched, I will write and remember; I engage in these acts already, but I will try to spend less time fretting over inevitable endings. Perhaps this is the first step towards finding a kind of love that does not devour me, towards knowing the value of my life and mind.

In 2016, I will live fiercely. Where I walk, I will strive to be remembered. With passion and precision, I will fall in love with what I am. I want to be adored: I want to suffer and survive until no one doubts that my resistance is also liberation, and that I am the the better for it. When I lose myself within a labyrinth of my own conflicted desires, as I always eventually do, I will be more and less than Icarus, still alive, still in flight, and burning, burning, burning; they will call my name on raucous evenings, and remember me on city streets when the night is gone.

As I write this, I am filled with a quiet joy. The ocean breathes, thirty feet below me. The stars blaze softly. This, right now, is one of those moments when I am really present. There are no barriers, no secrets, no lies left to tell. I am not distant. I am not guarded. I am whole. It does not matter if I keep these resolutions, because I have written them, and so have willed them into some sort of existence.

Maybe if I reckon with my pain instead of avoiding it, I will have nothing left to be afraid of. I know that I cannot have everything, but if I can create so much, and feel so deeply— even if I cannot necessarily survive it—then maybe I can start to make some sense of this inane world.

I will move slowly and determinedly towards a more harmonious state of being. The entire endeavor is cyclical, of course; I will inevitably become bored again, live within those psychological extremes that most people will never know, and when my mind and body have sufficiently consumed one another, I will ease myself out of insanity and adjust once more to the rational world. Maybe some part of me simply does not want to be sane; maybe that is why I am so incredibly inept when it comes to healing. But the present task is simple, an effort towards stability. I want to believe that I am capable of that.

I will try to remind myself that, in instances of loss, I am not always entirely at fault. My world changes, I grow older: the person remains, but the feeling they inspired fades to memory, and then to nothing at all. So I will refrain from crucifying myself, over and over again, on the transience and the tragedy of those pleading words—I need you to just hold on, until I am sane enough to love you again.

Am I really so alone? The only one grieving gently, the only one who retreats from the indifferent cold of an empty bed on sleepless nights? The only one who tires, at times, of being so deeply alive? Surely, somewhere, there is someone just as conflicted and impassioned and flawed as I am. Could we teach one another to feel more completely? Could we heal whatever mutual wounds our histories have inflicted? Could they make me feel safe again? Could they tell me who I am?

I will always be strange and I will always be displaced, because so much of my existence is determined by the perception and conclusions of a thousand other minds—such is the tragedy of the social world. But that is not so terrible: I can withstand the voyeuristic impulses of the culture I engage with, I can survive the stigmatization that I learned, in my early adolescence, to simply expect. And I can do so alone, if I have to.

Let me remember this moment. I love to know that I can feel this way. It is so rare and so strange, that I should exist and be heard. I am not sure who or what I am writing for now: lovers or strangers, confidants or companions, the woman I eulogized or the self I have yet to fully understand. But I will not apologize for this most recent engagement with the language of my own mind, however discursive or self-indulgent it may seem. I will not waste another year killing myself off for the respect of an audience that hardly exists. I will be different, and I will be better, for as long as I have the strength. I will write, and feel, and love, and burn, until there is nothing left to save.

© 2025 Forms of Boredom Advertised as Poetry

Theme by Anders Noren — Up ↑

Recent Comments