The question I am left with is the question of her loneliness.

And I prefer to put it off.

It is morning.

Anne Carson, The Glass Essay

A rooftop in Oxford; a flat in London; a valley in Nevada

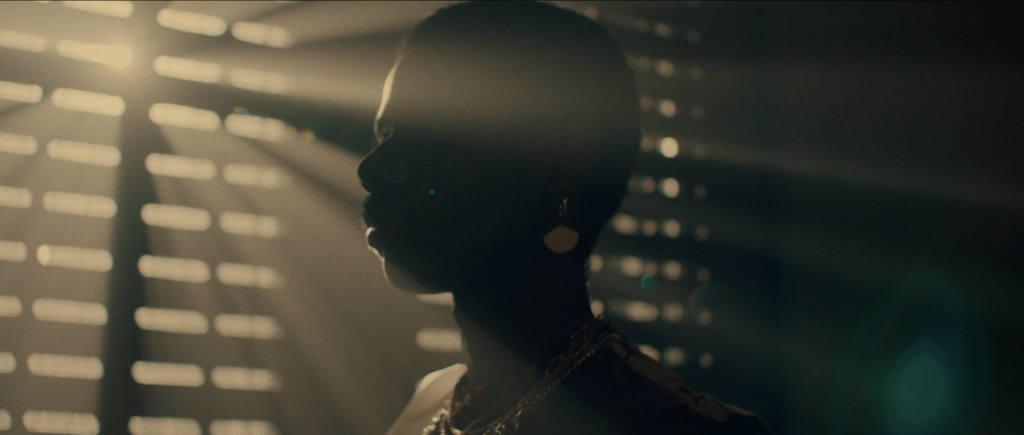

It is morning. I am ending. I stand above the city and I watch the world take form. I recall a dream from a childhood that is no longer mine. A clamor arises among the city bells, and each peal is agony: an invocation, a condemnation. Slick and damp, the rafters are numb to my lapsarian resolve, my pale impression of the morning star. Frost gives way to swollen drops of dew. First light creeps in along the eaves. Shadows lengthen across the bruised earth below.

I have been given everything. I have retained nothing. I gaze down at a world I cannot fathom, where lonely spires strike like brands against my sight. I taste exhilaration and defeat, surrender and some uncertain promise. It occurs to me that this might prove the most compelling moment of my tired existence: shivering beneath an iron sky, alone but for deleterious rooks in the far-flung belfries, the soles of my bare feet aching with cold and tensed against the unfeeling edge.

*

That was lifetimes ago. Even now, I don’t know why I did it. I don’t know why I didn’t. It was so close to happening differently. It does not matter now.

The year had played out as each one invariably does: marked by melancholy, mania, and inexorable desire. I lost myself in the ides of autumn, reveled in the austere glory of an ancient, sprawling city. But slowly, with the winter, my pleasure began to thin. My mind, a Cajun churchyard, drew the bones back to its surface. Nothing stays buried there long. So like the rains of late November, I wept and then froze over. My spectacle of promise delineated and digressed.

By springtime, I was festering. I tried to mend my ways. I committed to a kind of yearning for purpose: a parody of participation in a world that did not want me. A body that learns its longings, I thought, will be well remembered in the end. But I was wrong and that is how, in the abject ache of early spring, I came to share a sky with crows and sparrows.

It was as though I could sense, before it happened, the terrible summer to come. Even then, it was too late. Fate had dealt its hand despite my bitter protests. By August, hills would burn: my bones would break. I would languish like a garden swollen with weeds, tilled and seeded and with no one left to tend to it, hopelessly teeming with neglected life. The hours would howl on until I lowered myself at last, with porcelain beneath my elbows and damp hair in my eyes, into the throes of a terrible truth—a truth to make the waters run crimson, a truth to make the waters run clean.

*

So I fled the hell I once constructed with such care. I told myself that I was not the first to suffer in a world where faith crawls often on all fours. What of Ariadne, alone and awake, eyes dim with Naxos brine and surveying a labyrinth of grief? Those gilded threads, unspooling like nerves along the alleyways: a triumph to spell out the death of her world. I knew I could not follow her fate. I sought to find, like Dido, a home among the ashes.

But far from shelter, I found in the cinders another undoing. She had a poet’s soul and a songbird’s skill, and I loved her with a ferocity and a forthrightness that I will never again be mad enough to recreate. We were geniuses. We were fools. I felt certain we would share a grave. But when we destroyed each other we did so utterly. If she was oracular, then her will was an uroboros: it devoured itself each day. Choking on prophecies, the promises clenched like bay laurel between her teeth, my nightingale traded her tongue for tapestries. Still, I kept on loving her. For months we remained in sullen ecstasy, adrift in the sweetness of soon-to-rot things. Ours was a monstrous, miraculous folie à deux.

I only left because I had to. By then, her muteness had all but become my own. She awoke alone, but for a letter I wrote while she slept, and if it broke her heart (and I think it must have) then she never told me. She retreated instead into the ebbing currents of her intellect, those melancholy waters where I once loved her well, but where I leave her now undisturbed. In time, she has dwindled into what she is today: a phantom limb, a lovely echo of loss. My best friend and muse, my lover and my victim, reduced to a symptom of my contrary longings—hers is the voice in the dark I still listen for.

*

The one that followed was an accident, but I was grateful all the same. Time and again, strange luck ensnared our fortunes until, unable to evade one another any longer, we relented. By the time I dropped my bags on his sitting room floor, we had long since arrived at our shared conclusion.

I loved every inch of that stowaway place: the water-stained walls and peeling paint, linoleum littered with ashtrays, the decrepit stairwell and the pipes like blocked arteries. Curtains were drawn to arrest the air that had grown heavy with cigarette smoke and sweet with something stranger. Beyond the clouded glass, London clamored on without us. The sounds of the city rang out through the fog, but for us, the world ended at the window.

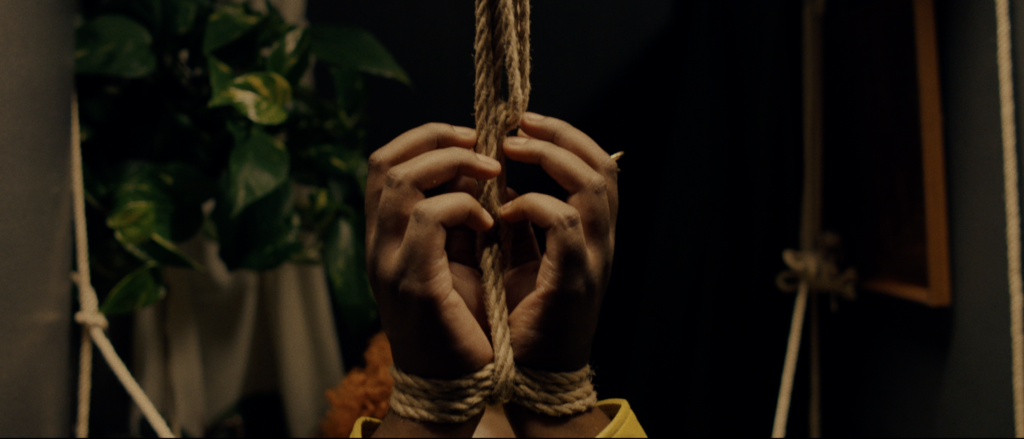

On that floor, for hours at a time, I would appropriate another woman’s love. With all the audacity of shared abandon, rough tenderness blunted my nascent misgivings. In taut knuckles and whites of the eyes, those patterns of bruises reappeared along my skin, nebulous and yellowing like thunderclouds. I learned another living language: the coarse hair, carelessly shorn; the jutting ridge to mark the glade of the hip; the sinew and warmth; the sharp line of the jaw. When you spend so long with a person, you learn their wants so well—better than you thought you would ever care to. And that is how I remember him still, in slipknots and laughter and the strange, bright blazon of his eyes. I was wrapped up, tangled, lost where I began, savoring those stolen hours of rest and respite. Kneeling, knowing, tasting, trying, sprawled against the threadbare carpet, fibrous impressions pressing into the skin like echoes of a familiar touch—we were content in a world we caressed into being, of which nothing remains now but us.

I loved him briefly, imperfectly, but happily in that furtive respite: our smuggler’s hold for the brilliance all broken things secretly share. I loved him there for as long as my imagination would allow, always knowing that, beneath our kindled pleasures, there were only the pecked-clean bones of her. And I know he knew it too, because once he took my face between his palms and said, why are you lost in your love of her? Why remain impaled upon one who almost killed you? And I said I don’t know, and it was true. I’ve never known.

I told him close to everything, but I never mentioned the spring morning when I stood atop the rafters. I never mentioned that shame. Because maybe I didn’t really mean it—what I meant to do, I mean. Maybe it all amounted to nothing. But then, I know it cannot have been nothing, because I never forgave myself for it. I forgave myself for everything else, but not for that.

*

Yes, in spite of all that has happened since, I still grieve for the moment on that rooftop. The older I get, the more of a toll the memory seems to take. Knowing that I am too young to think so does nothing to make it less true.

It was a terrible realization to come to nineteen months ago, in a forsaken corner of the arid Earth. Beyond the yawning gate, the desert stretched against my sight in paroxysms of silence and sand. The salt and sweat dried in crystal patterns on my neck, my bare shoulders blistered, a dry wind howled beneath a blood red sun. It was not beautiful, for all its barren splendor. It bore no meaning. It just seemed empty, more irretraceable than iridescent. It simply existed, obsolete and unchanging, inspiring nothing.

The first night in that valley was a gilded haze of smoke and grit through which my companions slept. I lay with my eyes open, sketching lazing, lovely azimuths as innumerable bats rustled overhead and constellations gripped the sky. In the absence of the moon, there was no real darkness: the luminous emptiness of the star-strewn wasteland drenched the sands below. I thought about how lucky I was, and how luck had nearly killed me. There was a kind of relief in my listlessness: it was as though the world had stopped breathing in its sleep. I wrote down reasons to stay there forever, in the dust that settled on the hood of my car. When the daylight returned, it brought with it a terrible heat that flung the earth into stasis. So I lingered for a while, and allowed the past to catch up with me. For once, I held my history’s gaze.

It was then, for no real reason, that it came to me—the overdue indictment, the truth tasting of kerosene. I realized that I was going to get older, and the world was going to get stranger, and none of this was going to get any better.

The fact of the matter is this: I know that something is wrong with me. You think I don’t know it, but I do. I am quite as unsettled as any of you. I see when the world turns its back, mortified by my needs. And I never wonder, for I am the sharp-edged sum of a splintered childhood. Hateful memories in aggregated shards comprise me. I am deficient in all of the worst ways: I am cynical, where I should be credulous. I am secretive, where I should be sincere. I am selfish, sightless, and self-mutilating: my hatred is untenable, my affections still more so. Anyone who has ever loved me has been punished for it. And worse than that, worse than anything—I am afraid of my own mind. I am afraid to know what it is or is not capable of.

But I was not always like this. My mind was a decent thing, once, it really was. It just could not keep pace with the pulse of the waking world. I think that, over time, I lost my resolve. That is the truth to which I am condemned: the certainty that animates the scars. Time and again, I played my hand wrong. I should never have wondered. I should never have waited. I should have taken my silver—all thirty pieces—and walked away crueler, but clean.

Now, immutable, carrying on past the present, past-to-present, the past becomes a presence. Each day, I stand alone on a clandestine shoreline where every decision I make is both crucial and in vain. Nightly, I traverse a theatre of my own antiquities. Liminal and limitless, taciturn and twice the stranger, I hover at the threshold. My reckoning, I know, will come wearing yesterday’s clothes.

*

Just let it go. You never left. Let it go. Why can’t I do it over? As a dog gnaws bones, I savage the marrow of my past. Maybe I am out of chances. Maybe, when I falter, it will be fixed. My final moment could define me—who in this world does not live for that? But I am not lost, not at all. I live and write on borrowed time. I am lucky. I am damned. I am a liar without an excuse.

It is a purgatory no scripture accounts for: the gulf that lies between me and nothing, which is the converse of temporary, which is the crux of matter and meaning. That crisis of my being, which leans towards death, bears in it the promise of ephemerality. That last moment extends forever. God forsake me, I can’t fix it. I’ve got to live with it. I cannot fix it. I have to continue. I have to try.

I will be standing on that rooftop for the rest of my life.

Recent Comments